Teisė ISSN 1392-1274 eISSN 2424-6050

2024, vol. 132, pp. 135–144 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Teise.2024.132.10

Teisės aktualijos / Problems of Law

Karan Choudhary

ORCHID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6621-0962

Ph.D. (Law) from National Law University Delhi

and Université Paris Nanterre, France.

Judge, Under aegis of Hon’ble Delhi High Court,

Sher Shah Road, New Delhi - 110503, India.

Phone: 0091-9013404949

E-mail: (Official) karan.choudhary@aij.gov.in

(Preferred) kch.mac007@gmail.com

Karan Choudhary

(Université Paris Nanterre (France), National Law University Delhi (India))

Summary. This article scrutinises research methods for conducting research in the discipline of Law. Quality legal research, whether in the form of a research article, a thesis, a dissertation or any other, is a mere consequence of a meticulously planned research methodology. Protagonists of new research methods argue that renaissance in legal methods is needed to ensure the relevancy of Law as a subject in the present times, and also to find meaningful solutions to real life problems concerning Law. Traditionalists, however, vouch for the relevancy and continued importance of the traditional methods in legal research. Upon analysing various research methods, the author finds that the choice of research methods is contingent upon the understanding/perception of Law, and develops a visual representation of that idea. It has also been determined that research methods from social science are also being used in the legal research with the view to make the legal system more effective. The author argues for a multi-method legal research to arrive at more comprehensive output and to solve real life problems concerning Law.

Keywords: Legal research, Legal research methodology, Legal research methods, Multi-method legal research

Karan Choudhary

(Paryžiaus Nantero universitetas (Prancūzija), Nacionalinis teisės universitetas Delis (Indija))

Santrauka. Šiame straipsnyje išsamiai nagrinėjami teisės disciplinos tyrimų atlikimo metodai. Kokybiški teisiniai tyrimai, nesvarbu, tai būtų tiriamasis straipsnis, baigiamasis darbas, disertacija ir kt., yra tik kruopščiai suplanuotos tyrimo metodologijos rezultatas. Naujų tyrimo metodų šalininkai teigia, kad teisinių metodų atnaujinimas reikalingas siekiant užtikrinti teisės kaip fenomeno aktualumą šiais laikais, taip pat rasti prasmingus realių su teise susijusių problemų sprendimus. Tačiau tradicionalistai garantuoja tradicinių metodų aktualumą ir nuolatinę svarbą teisiniams tyrimams. Autorius, analizuodamas įvairius tyrimo metodus, įsitikino, kad tyrimo metodai priklauso nuo teisės supratimo / suvokimo, ir plėtoja vizualinį tos idėjos vaizdą. Nustatyta, kad teisiniuose tyrimuose taip pat naudojami socialinių mokslų tyrimo metodai, siekiant teisinės sistemos efektyvumo. Autoriaus teigimu, keliais metodais grindžiami teisiniai tyrimai būtų išsamesni ir leistų išspręsti realias su teise susijusias problemas.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: teisiniai tyrimai, teisės tyrimo metodika, teisės tyrimo metodai, daugiametodis teisinis tyrimas.

________

Received: 21/03/2024. Accepted: 26/06/2024

Copyright © 2024 Karan Choudhary. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Legal research plays the pivotal role in the discipline of Law. Its importance can be witnessed in all the activities of Law, such as the expansion of frontiers of the discipline towards solving legal problems both of the local and the global concern. From a student’s perspective, carrying out research assignments requires sound understanding of the legal research methodology. From the legislature perspective, promulgation of Law which addresses – or seeks to address – socio-legal problem and/or ameliorate the living standards and/or promote the quality of life requires solemn legal research. Choudhary (2022, p. 96) observes that the lack of legal research by legislature for instance, lack of a feasibility study and impact analysis before promulgating a new law leads to more serious issues.1 In the Common Law tradition, courts solve legal problems by conducting legal research, and, thereby, courts also develop the corpus of decisions and Law per se. In other words, as Prof. Bhat (2019, p. 14) notes, “All personnel in the field of legal profession, whether a law student, lawyer, judge, researcher, law teacher, law officer, legal advisor, legislative draftsman, legal journalist, Law Commission member, treaty negotiator, or legal expert, knowingly or unknowingly, use the methods of legal research and need to uphold the standards of good quality legal writing for providing satisfactory legal service.”

The aim of this article is to critically analyse various research methods in the legal research. Through the analysis, the author also seeks to engage with the discourse in the legal research methodology which calls for new methods and approaches to find meaningful solutions to legal problems concerning real life. Penultimately, it seeks to enhance the understanding of the research methods in Law and thereby facilitate the selection of the appropriate research method, especially for beginners in the legal research. This study uses various documents such as legal texts, books, court decisions, scientific articles, and research papers concerning the legal research methodology. For this article, doctrinal, analytical and historical methods are used with analysis relying upon formal logical tools.

Legal Research is a systematic study of legal fact or a bundle of legal facts, constituting a legal problem, located in its natural context i.e., in situ or outside the natural context, i.e., ex situ. It is carried out with an aim/objective which often is to solve the legal problem.

For example, it may be studied whether same-sex marriage can be given legal recognition in a particular country, say, for instance, in the Republic of Lithuania. Here, the legal problem which calls out for our attention is the ‘legal recognition of same-sex marriage’. It, by itself, is based on a bundle of legal facts, for instance, the legal recognition of same-sex individuals, the legal autonomy of same-sex individuals, the legal rights of same-sex individuals, and other points. Furthermore, the said legal problem is situated/located in the Republic of Lithuania, which also adds to the bundle of legal facts, namely, whether the laws generally in Lithuania allow for or are conducive to the legal recognition of same-sex marriage – whether same-sex relationship is criminalised/de-criminalised, whether the legal culture is conducive to or homophobic to the notion of same-sex marriage and other issues. Let us flag this example for later references.

Prof. Bhat (Bhat, 2019, p. 11) observes that legal research can be regarded as “research conducted in the field of law addressing any specific problem in the matter of legal norm, policy, institution, or system; bringing out its implication, background, application, functioning, and impact; assessing its outcome, efficacy, suggesting the lines of reform and thereby answering the problem at hand.” Meanwhile, legal research involves “sincere and dispassionate investigation on any research problem in the domain of law selected by a researcher by formulation of research plans; by choice of appropriate tools for data collection; and by systematic arrangement and interdisciplinary analysis of materials undertaken either under supervision or independently and resulting in a report, article, or book of publishable quality” (Bhat, 2019; quoting Wortley, 2010, p. 5–10). Now, let us comprehend the domain of legal research.

Law has long been understood as a distinct field of study2 and research (Zeigler, 1988; Posner, 1987). For instance, it is different and distinct from subjects such as history, economics, sociology, psychology, anthropology and others. However, some scholars challenge the distinctiveness of Law and argue that legal problem(s) can be studied by other disciplines (Balkin, 1996; Cotterrell, 1998; Frankfurter, 1930). Hence, there exists sociology of Law, Law and economics, legal anthropology and others. According to Balkin (1996), since Law is less academic and more skill-oriented as a professional discipline, its domain would be easily invaded by methods of other social sciences. Complacent with catering to the profession, legal education found it comfortable to borrow from other disciplines. Cotterrell (1998, p. 181–182) observes in the context of sociology of law that “sociological insight is simultaneously inside and outside legal ideas, constituting them and interpreting them; sometimes speaking through them and sometimes speaking about them. Thus a sociological understanding of legal ideas does not reduce them to something other than law. At the same time law defines social relations and influences the shape of the very phenomenon that sociology studies. Thus legal and other social ideas interpenetrate each other.”

Therefore, we see that the domain of Law is independent and autonomous. However, other subjects do engage with legal problem(s) and offer their insights. Now, it is important to comprehend the evolving understanding of Law.

It is important to understand Law, as the choice of the research method is itself contingent upon the understanding of Law. Initially, the ‘black letter’ of Law was understood to be the complete picture of Law. Therefore, a legal researcher could circumscribe their research to the black letter of Law. However, with the passage of time, it was realised that mere reading and understanding Law in the way it exists in textbooks and/or court decisions does not necessarily present the complete picture. It is no coincidence that long back, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (Holmes, 1897, p. 469) wrote in Harvard Law Review that “[F]or the rational study of law the black-letter man may be the man of the present, but the man of the future is the man of statistics and the master of economics.” Loevinger (1971) added jurimetrics to the Holmes-drawn list. Sandgren (2000) argues for a renaissance in Law to ensure revitalisation and continued relevance of Law as a discipline. Schrama (2011) calls for inter-disciplinary legal research for making legal system more effective (also, see Hutchinson, 2015). Choudhary (2019) observes and highlights the need for trans-disciplinary research in Law in order to find meaningful solutions to real life problems concerning Law and designing justice-conscious remedies.

Real life problems do not present themselves as a problem located in water-tight compartments fashioned according to disciplines. One needs to be conscious of the interconnectedness of things, intersectionality, inter-sectoral dimension, trans-disciplinarity, comparativeness, gender dimensions and others. For instance, clearing snow in a municipality has apparently no connection with gender. However, Perez (2019) chronicles the traditional snow clearing approach of Karlskoga in Sweden which mandated the major road for cars to be cleared first, and only then streets, bus stops, pedestrian and walkways and bike paths. Women usually walk, cycle and use public transport more than men. Hence, the way the municipality cleared snow favoured car users, and thereby had different effects on men and women. Accordingly, the snow clearing approach was reconsidered, and priorities were changed, i.e., pedestrian walkways and bike paths were cleared before roads. It did not cost anything, yet it made the town more accessible to everybody.

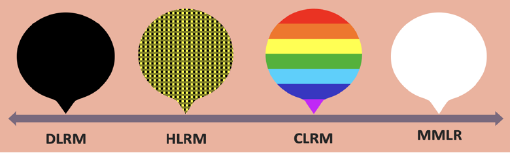

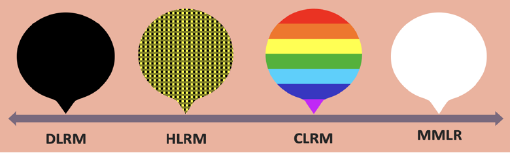

Fig. 1. Illustrative spectrum of legal research methods and corresponding understanding of law. Developed by the author

Figure 1 contains four speech bubbles. Each bubble represents an understanding/perception of Law and, correspondingly, the appropriate legal research method. The captions state the appropriate legal research method based on particular understanding of Law. On the left side of the spectrum lies a black bubble. Here, Law is understood as black letter Law. Law is found in texts of statute books, codes, legislations, court decisions and others. The doctrinal legal research method (DLRM) is appropriate for such understanding of Law, for example, it involves using DLRM for legislative interpretation. The second bubble on the left is yellow and black. Law is not merely black letter Law, but it also accommodates the historical dimension (represented by the yellow colour). Here, both historical and legal facts are taken into consideration for the better comprehension of law, i.e., the historical legal research method (HLRM) is involved. Law is found in texts, but also the historical perspective of Law, its evolution and development are also studied and considered. It takes us beyond the dead black letter of Law. In accordance with the statement by Justice Holmes, the yellow colour can also represent economics, and, in that case, black and yellow would mean Law and economics. Or else, yellow could also be considered a social fact. Hence, sociology of Law would be a mélange of legal and social facts. Here, Law is not only informed from the traditional legal texts, but it also invites inputs from economics/statistics/sociology and others. The third bubble from the left is a bubble containing many colours. It has many colours because it also simultaneously enquires into legal stances/solutions that have been designed by various jurisdictions facing the same or similar legal problems. The comparative legal research method (CLRM) is appropriate for such a perception of Law which acknowledges Law in different legal traditions and jurisdictions. The final bubble, i.e., the one on the right, is white in colour. When light is passed through a prism, it splits into the constituent ‘VIBGYOR’ colours. However, when all those colours are recombined, it results in the white light. Here, white is representative of a combination of methods, i.e., the multi-method legal research (MMLR). Real life solutions require real life understanding of Law, i.e., Law in action. Law is extracted from texts, and it is also observed how it operates in the real world where we live. This multitude of inputs, be it from the critical legal sense/feminist perspective or others, enriches the understanding of Law (Nielsen, 2012; Bhat, 2019, p. 469–496). It enables us to design meaningful solutions to real life problems pertaining to Law. Often, those problems are not visible from/to the traditional legal research methods. Perhaps, that is the reason why we saw the birth of the feminist research methods (Bartlett, 1990). We must remind ourselves that this is an illustrative spectrum. There can be more bubbles depending on the variety of understandings/perceptions of Law and the research methods. However, the purpose of this figure is to depict the nexus between the research method and a particular understanding of Law. A researcher might intentionally select DLRM over MMLR depending on various factors, such as the research problem, the research aim/objectives, the research budget and others.

Let us have a more nuanced look at the legal research methods.

Is there a toolkit for researcher in legal science just like a carpenter’s toolkit? Researchers in natural science experiment in laboratories to unearth new scientific discoveries. For instance, they unearthed the double helix structure of DNA. But what about researchers in Law?

Christopher C. Langdell, Dean of Harvard Law School from 1870 to 1895, preferred to call Law a legal science and the Law library as a lawyer’s laboratory. He observed that “[T]he work done in the library is what the scientific men call original investigation. The library is to us what a laboratory is to the chemist or the physicist, and what a museum is to the naturalist” (Kimball, 2009, p. 349). This also highlights the importance of the doctrinal legal research method and its stronghold over legal science, which Barite (2010, p. 350) refers to as ‘doctrinalism’. Therefore, we see that desk-based research/hermeneutical research has been the mainstay of legal research as opposed to ‘field’-based research which is mostly used in social sciences. For example, survey or interview methods to collect data in sociology/anthropology/ethnographical researches are distinct from the case-based method of establishing Law through analysis of precedent(s) by using documents as the source material. Based on the purpose of research, legal research can be divided into descriptive, evaluative, explanatory, exploratory, law reform-oriented, action-oriented (see Lewin, 1946), socio-legal and others. The terms are self-explanatory, for instance, descriptive research “aims to systematically describe the background, development, phenomenon, and application of legal norms, legal institutions, and mechanisms. It gathers data, maps the whole regime in its continuity and summarizes its prevalent position” (Bhat, 2019, p. 20).

Legal Research methods can be broadly classified as dyads of qualitative vs. quantitative, empirical vs. non-empirical, doctrinal vs. non-doctrinal, applied research in Law vs. basic/fundamental research in Law. All these dyads are interrelated. What concerns the Qualitative and Quantitative research methods – both of them rest on different epistemologies: the quantitative methods are often associated with deductive reasoning, while the qualitative methods often rely heavily on inductive reasoning. The qualitative method identifies the presence or absence of something, in contrast to the quantitative method which involves measuring the degree to which some feature is present (Kirk and Miller, 1986, p. 9). To appreciate the difference between them, let us consider an example of crime rates. Nielsen, by using this example (2012, p. 952), states that “a crime rate seems to be the quintessential ‘how much?’ question. How often does a particular crime occur? seems best answered using quantitative methods.” In the United States of America, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) periodically releases a crime statistics report titled ‘Crime in United States’. Similarly, in India, the Nation Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) annually releases crime statistics report titled ‘Crime in India’. Thus, whenever, there is a need to measure, or count, the quantitative methods are used. Collecting data is costly, labour-intensive, and time-consuming. This perhaps can be one of the reasons for the aversion of a legal researcher to the empirical/quantitative research methods. This is coupled with the difficulties in obtaining valid and reliable conclusion from a comparatively small sample size. However, with an increased access to data/information, be it in form of published governmental reports or others, the things are changing. There is advancement in technologies, which aids in solving complex calculations at the click of a computer button. We see journals such as ‘Journal of Empirical Legal Studies’ solely focusing on empirical researches in Law. Another example can be that of food items in restaurants in a locality. If one wants to know what is the most popular, i.e., the most commonly sold dish in restaurants in a particular locality in a given point of time, one needs to use quantitative research methods. However, to answer the question why that particular food item is the most popular/sold, one needs to select the qualitative research methods. In crude simplification, Doctrinal research is Qualitative research, and Empirical research is Quantitative research. However, there can be Qualitative approaches to the empirical legal research (Webley) and Quantitative approaches to the empirical legal research (Epstein and Martin, 2012).

Empirical legal research is viewed “as the study of law, legal process, and legal phenomena using social science research methods, such as interviews, observations, or questionnaires” (Burton, 2013). According to Peter Cane and Herbert Kritzer (Kritzer, 2012, p. 1–8), empirical legal research involves “systematic collection of information (data) and its analysis according to some generally accepted method. For data collection, it uses tools such as survey, observation, interview, case study, questionnaire, experiments, documents, decisions, and events. Empirical legal research may focus on actors of the legal profession or its consumers and beneficiaries.” As per Epstein and King (Epstein and King, 2002), “what makes research empirical is that it is based on observations of the world, in other words, data, which is just a term for facts about the world. These facts may be historical or contemporary, or based on legislation or case law, the results of interviews or surveys, or the outcomes of secondary archival research or primary data collection. As long as the facts have something to do with the world, they are data, and as long as research involves data that is observed or desired, it is empirical.” Empirical research in Law involves “the study, through direct methods rather than secondary sources, of the institutions, rules, procedures, and personnel of the law, with a view to understanding how they operate and what effects they have. It is not a synonym for ‘statistical’ or ‘factual’ research” (Baldwin and Davis, 2003).

The doctrinal legal research method (DLRM) is the mainstay research method in Law. It is professionally a more popular method of the legal research and is most frequently applied, so much so that “unfortunately the doctrinal method is often so implicit and so tacit that many working within the legal paradigm consider that it is unnecessary to verbalise the process” (Hutchinson and Duncan, 2012, p. 99). It involves “analysis of case law, arranging, ordering and systematising legal propositions, and study of legal institutions, but it does more, it creates law and its major tool (but not the only tool) to do so is through legal reasoning or rational deduction” (Bhat, 2019, p. 145). It is often criticised as desk research and often labelled as hermeneutical research. Going back to the flagged example ‘whether same-sex marriage should be given legal recognition in the Republic of Lithuania’, DLRM will cull out that, as Article 38 in Chapter Three Society and the State of the Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania reads as “Marriage shall be concluded upon the free mutual consent of man and woman.”3 Furthermore, the Civil Code of the Republic of Lithuania also contains relevant provisions to the ‘concept of marriage’ and ‘legal consequences of agreement to marry’. Other research methods invite inputs from other domains which can also be illuminating. For instance, the reaction of society to imaginary tales can be worth consideration. A fairy tale depicting marriage between same-sex persons was censored4 by the Republic of Lithuania (for more see, Macatė v. Lithuania), which speaks volumes about the legal mentalité (Legrand, 1996). This is a comparative legal research method input. The empirical research methods can give inputs regarding real-time discrimination faced by individuals on the basis of their sexual orientation and gender identity by utilising both quantitative and qualitative tools. Another example of DLRM is the ruling of the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Lithuania that The Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence, also known as the Istanbul Convention, does not contradict the Lithuanian Constitution (Decision dated 14 March 2024, No. KT24-I1/2024, File No. 18/2023).

Prof. Bhat (Bhat, 2019, p. 474–480) notes that “it is high time to move beyond the broad divisions of ‘doctrinal’ and ‘empirical’ research. This does not mean that the broad divisions are not necessary, but only that they are not sufficient and in constant need of realignment.” The multi-method legal research (MMLR) is a meta-method ‘that makes use of more than one research method, techniques or strategies to study one or more closely related legal issues’ or a ‘sequential or simultaneous application of multi-method research’. What cannot be done by the single-method approach can be done by MMLR with a greater efficiency and synergy, and towards a more comprehensive output. Nielsen (2012) shares an Indian parable describing blind men (or men in the dark) feeling (empirically researching) an elephant. The man who feels the tail reports that the elephant is like a brush, the man who feels the tusk says the elephant is like a spear, the man who touches the side reports that the elephant is like a wall, and the man who feels the ear describes the elephant as resembling a fan. MMLR uses multiple perceptions and realities to arrive at better/comprehensive solutions. Therefore, we witness myriads of legal research methods available to a legal researcher. There are advantages and disadvantages with any research method. The researcher must take into consideration the limitations before selecting a legal research method.

Any legal research needs a lucid roadmap for an intellectual sojourn. The researcher must conduct sincere and dispassionate investigation based on scientific principles, such as objectivity. One must keep in mind Kipling’s six honest men (Kipling, 2010):

I keep six honest serving men,

they taught me all I know;

Their names are what why and when,

And how and where and who.

The Legal Researcher must keep abreast with the legal developments and also know the legal context and history. The Research Problem is the heart of any legal research. The Research Design must be meticulously drafted. The Review of Literature is a must for the comprehension of the research terrain regarding the research topic. As regards the choice of the legal research method, it depends on various factors, such as the perception/understanding of Law, the research problem, the research budget, the aim(s) and objectives of the study. If a researcher is required to give, for example, legal interpretation, DLRM will be the best method. However, for developing a law and a policy to address a particular social reality/problem, for instance, domestic violence, MMRL will be better. For gauging the quality of free legal aid at the trial courts level, empirical legal research method will be more appropriate. If Law is understood in the legal pluralist sense as opposed to the state-centrist sense (see Griffiths, 1986), then, Menski’s kite-based research method (Menski, 2011) will cater well. The author has already discussed the nexus between the perception/understating of Law and the legal research methods (refer to Figure 1). Therefore, various methods can be used to identify, retrieve and analyse the information which is necessary to support legal decision making.

Legal research plays the pivotal role in the discipline of Law. Quality legal research, whether in the form of a research article, a thesis, a dissertation, etc. is mere consequence of a meticulously planned research methodology. Perceptions/understandings of Law, inter alia, guide the selection of the research methods. Even though legal research methods are distinct, however, legal problems are being studied by other disciplines using their own methods. Interdisciplinary researches including socio-legal studies have also enriched Law and assisted in making the legal system more effective. This has increased the choices of the research methods available to a legal researcher. The availability of research methods from other social sciences and disciplines is in no way a threat to the autonomy of Law as a discipline. It is also to be kept in mind that each research method has its own limitations. It is not surprising that feminists have proposed their own feminist method of research. Ultimately, it is evident that the multi-method legal research is the need of the hour to solve real-life problems concerning Law and designing justice-conscious remedies. However, this does not mean that other research methods have lost their relevance.

Bhat, P. I. (2019). Idea and Methods of Legal Research. India: Oxford University Press.

Kimball, B. A. (2009). The Inception of Modern Professional Education: C. C. Langdell, 1826–1906. University of North Carolina Press.

Kipling, R. (2010). Just So Stories. North Carolina: Yesterday’s Classic.

Kirk, J. and Miller, M. L. (1986). Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Sage Publications.

Perez, C. C. (2019). Invisible Women: Data Bias in World Designed for Men. Vintage Publishing.

Baldwin, J. and Davis, G. C. (2003). Empirical Research in Law. In: P. Cane and M. Tushnet (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Legal Studies. Oxford University Press, pp. 880–900.

Burton, M. (2013). Doing Empirical Research. In: D. Watkins and M. Burton (eds.). Research Methods in Law. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Publication, Routledge, pp. 55–70.

Cane, P. and Kritzer, H. M. (2012). Introduction. In: P. Cane and H. M. Kritzer (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research. Oxford University Press, pp. 1–8.

Epstein, L. and Martin A. D. (2012). Quantitative approaches to empirical legal research. In P. Cane and H. M. Kritzer (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research. Oxford University Press, pp. 901–925.

Nielsen, L. B. (2012). The Need for Multi-Method Approaches in Empirical Legal Research. In: P. Cane and H. M. Kritzer (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research. Oxford University Press, pp. 951–975.

Webley, L. (2012). Qualitative approaches to empirical legal research. In: P. Cane and H. M. Kritzer (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research. Oxford University Press, pp. 926–950.

Wortley, B. A. (2010). Some reflections on legal research. In: S. K. Verma and A. Wani (eds.) Legal Research and Methodology. Delhi: The Indian Law Institute, pp. 5–10.

Choudhary, K. (2019). Techno-Legal Synergy: Trans-disciplinary Research in Law. In: Law 2.0: New methods and new laws, Conference papers. Vilnius: Vilnius university Press, pp. 59–65. Available at: http://lawphd.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Final-leidinys.pdf

Balkin, J. M. (1996). Interdisciplinarity as Colonization. Washington and Lee Law Review, 53(3), 949–70 [online]. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol53/iss3/5

Bartie, S. (2010). The Lingering Core of Legal Scholarship. Legal Studies, 30(3), 345–369 [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-121X.2010.00169.x

Bartlett, K. T. (1990). Feminist Legal Methods. Harvard Law Review, 103(4), 829–888 [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/1341478

Choudhary, K. (2022). Human Rights Court in India: Key Legal Concerns. Journal of Indian Law Institute, 64(1), 86–99.

Cotterrell, R. (1998). Legal theory and Social Sciences. Journal of Law and Society, 25, 181–182.

Epstein, L. and King, G. (2002). The Rules of Inference. University of Chicago Law Review, 69(1), 1–133 [online]. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclrev/vol69/iss1/1

Griffiths, J. (1986). What is Legal Pluralism? The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 18(24), p. 1–55 [online]. Available at: 10.1080/07329113.1986.10756387

Holmes, O. W. (1897). The Path of the Law. Harvard Law Review, 10(8), 457–478 [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/1322028

Hutchinson, T. (2015). The Doctrinal Method: Incorporating Interdisciplinary Methods in Reforming the Law. Erasmus Law Review, 3, 130–138 [online]. Available at: 10.5553/ELR.000055

Hutchinson, T. and Duncan, N. (2012). Defining and Describing What We Do: Doctrinal Legal Research. Deakin Law Review, 17(1), p. 83–119.

Legrand, P. (1996). European Legal Systems Are Not Converging. The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 45(1), 52–81.

Levine, K. L. (2006). The Law is not the Case: Incorporating Empirical Methods into the Culture of Case Law Analysis. University of Florida Journal of Law & Public Policy, 17, 283–302.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 34 –46 [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1946.tb02295.x

Loevinger, L. (1949). Jurimetrics: The Next Step Forward. Minnesota Law Review, 33(5), 454–493 [online]. Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/1796

Menski, W. (2011). Flying Kites in a Global Sky: New Models of Jurisprudence. Socio-Legal Review, 7(1), 1–22 [online]. Available at: https://repository.nls.ac.in/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1199&context=slr

Posner, R. A. (1987). The Decline of Law as an Autonomous Discipline 1962–1987. Harvard Law Review, 100(4), 761–780 [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/1341093

Posner, R. A. (1988). Conventionalism: The Key to Law as an Autonomous Discipline? The University of Toronto Law Journal, 38(4), 333–354 [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/825687

Sandgren, C. (2000). On Empirical Legal Science. Scandinavian studies in law, 40, 445–482.

Schrama, W. (2011). How to carry out interdisciplinary legal research: some experiences with an interdisciplinary research method. Utrecht law review, 7(1), 147–162 [online]. Available at: 10.18352/ulr.152

Ziegler, P. (1988). A General Theory Of Law As A Paradigm For Legal Research. The Modern Law Review, 51, 569–592 [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2230.1988.tb01773.x

Legal Acts

Law of India “The Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 [online]. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15709/1/A1994____10.pdf

Law of Lithuania “Law on The Protection of Minors against The Detrimental Effect of Public Information”, 10 September 2022, No IX-1067 [online]. Available at: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.363137?jfwid=rivwzvpvg#:~:text=This%20Law%20shall%20establish%20the,as%20institutions%20carrying%20out%20the

Macatė v. Lithuania [ECHR], No. 61435/19, [23.01.2023]. ECLI:CE:ECHR:2023:0123 JUD006143519 [online]. Available at: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre?i=002-13955

The Ruling of the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Lithuania of 14 March 2024. No. KT24-I1/2024, File No. 18/2023 [online]. Available at: https://lrkt.lt/lt/teismo-aktai/paieska/135/ta2975/content

|

Karan Choudhary is a Judge in India. He is a Ph.D. in Law from Université Paris Nanterre and National Law University, Delhi. He is a former recipient of prestigious Erasmus funding. His research interests include Law and policy, Law and culture, Law and literature, Music Law, legal research methodology, and indigenous rights. Karan Choudhary yra teisėjas Indijoje. Jis yra mokslų daktaras, baigęs teisės studijas Paryžiaus Nantero universitete ir Valstybiniame Delio universitete. Jis yra buvęs prestižinio Erasmus finansavimo gavėjas. Autoriaus moksliniai interesai apima teisę ir politiką, teisę ir kultūrą, teisę ir literatūrą, teisės tyrimų metodologiją, čiabuvių teises. |

1 Author herein critiques, Delhi Gazette Notification F. No. 6/13/2011-Judl./Suptlaw/1132-1137 dated November 24, 2020 in the context of the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993.

2 Richard A. Posner preferred to call Law an autonomous discipline.

3 Amendments, if any, need to be checked.

4 Distribution of the book was temporarily suspended. Later on, the distribution was resumed with the book containing a warning label stating that its contents could be harmful to children under the age of 14, as it encouraged a different concept of marriage and the creation of a family from the one enshrined in the Lithuanian Constitution and Law.