Taikomoji kalbotyra, 20: 74–88 eISSN 2029-8935

https://www.journals.vu.lt/taikomojikalbotyra DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Taikalbot.2023.20.6

Zsófia Ludányi

HUN-REN Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics, Eszterházy Károly Catholic University

ludanyi.zsofia@nytud.hun-ren.hu

Ágnes Domonkosi

HUN-REN Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics, Eszterházy Károly Catholic University

domonkosi.agnes@nytud.hun-ren.hu

Abstract. Applying the framework of Language Management Theory, the paper explores how language consulting services may be involved in the management of various language problems experienced by speakers. Focusing on the discourse-shaping activity of everyday speakers, Language Management Theory is a comprehensive theoretical framework aimed at the detection, analysis and treatment of linguistic and communicative problems. One viable path toward solving language problems is for language users to contact a language consulting service. The paper shows how the Language Consulting Service of the HUN-REN Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics applies problem-management practices to the spelling and language use problems of inquirers. The practice of institutional language consulting provides a bridge between simple and organised language management processes, and between the micro and macro levels of management. In today’s complex linguistic context, which promotes linguistic diversity, the role of language consulting services is primarily to provide a data-driven and discursive approach to language problems, working closely with the language users themselves.

Keywords: language management, Language Consulting Service, Hungarian, language problems and solutions, spelling problems, correctness

Santrauka. Šiame straipsnyje, pasitelkiant kalbų vadybos teorijos prieigą, nagrinėjama, kaip kalbinių konsultacijų paslauga gali pasitarnauti sprendžiant įvairių kalbėtojų patiriamus kalbinius iššūkius. Kalbų vadybos teorija, orientuota į kasdienį kalbėtojų diskursą kuriančią veiklą, yra visapusiška teorinė sistema, skirta kalbinėms ir komunikacinėms problemoms nustatyti, analizuoti ir spręsti. Vienas iš galimų būdų sprendžiant kalbines problemas yra kalbos vartotojų kreipimasis į Vengrų kalbos konsultacijų tarnybą. Straipsnyje aptariama, kokią Vengrijos kalbotyros tyrimų centro Kalbos konsultacijų tarnyba taiko problemų valdymo praktiką besikreipiančių asmenų rašybos ir kalbos vartojimo problemoms spręsti. Institucinė kalbinių konsultacijų praktika yra tiltas tarp natūralių ir koordinuotų kalbos valdymo procesų bei tarp mikrolygmens ir makrolygmens vadybos. Šiandienis sudėtingas kalbinis kontekstas skatina kalbinę įvairovę, tad kalbinių konsultacijų paslaugos vaidmuo pirmiausia yra teikti duomenimis pagrįstą ir diskursyviu požiūriu į kalbinius iššūkius paremtą pagalbą, glaudžiai bendradarbiaujant su pačiais kalbos vartotojais.

Raktažodžiai: Vengrų kalbos konsultacijų tarnyba, vengrų kalba, kalbų vadyba, kalbinės problemos ir sprendimai, rašybos problemos, taisyklingumas

_______

• The paper was supported by the Visegrad Scholarship #52311005 (Á. D.) and by the NKFIH grant K 129040 (Á. D.).

Copyright © 2023 Zsófia Ludányi, Ágnes Domonkosi. Published by Vilnius University Press.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

The paper applies the framework of Language Management Theory (Jernudd–Neustupný 1987; Kimura–Fairbrother eds. 2020; Nekula–Sherman–Zawiszová eds. 2022) to show how language consulting services may be involved in managing various language problems experienced and reported by speakers. Building on the work of the Language Consulting Service (LCS) of the HUN-REN Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics, the paper presents case studies of language problem management practices, also illustrating how individual speakers’ language problems are embedded in more complex language management processes. The main research question of the paper is how language consulting plays a role in bridging the gap between simple and organised language management processes, i.e. between the micro and macro levels of management (Kimura & Fairbrother eds. 2020).

Firstly, the paper briefly presents Language Management Theory as a theoretical framework for addressing language problems (2.1). Subsequently, it outlines the role of language consulting services in language management processes (2.2) and describes the language consulting activity of the Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics (3). This is followed by an analysis of responses to some LCS inquiries on normative spelling (4.1) and language use (4.2).

Language Management Theory is a comprehensive theoretical framework aimed at the detection, analysis and treatment of linguistic and communicative problems (Jernudd–Neustupný 1987). The theory has its roots in language planning theory (Nekvapil 2006). The main difference between Language Management Theory (LMT) and language planning theory is that in language planning processes, language problems to be solved are identified by professionals, while LMT focuses on problems reported by individual language users, adopting a characteristically bottom-up approach (Nekvapil–Sherman 2015).

LMT zooms in on the discourse-shaping activity of everyday speakers, and its central concept is the language or communication problem (cf. Jernudd 1991). In this interpretation, a language problem is any linguistic phenomenon which triggers some kind of reflection from the speaker, the speech partner or even an external observer. Language management is the activity of detecting and addressing language problems, which includes reflection on them and the related language-shaping activity.

LMT models the language management process as a cycle consisting of the following steps (Jernudd–Neustupný 1987: 78–80; Nekvapil 2009: 3–4): (1) language is monitored by speakers and deviations from norms are noted (noting); (2) deviations from norms are evaluated (evaluation); (3) an action plan is designed (adjustment design); (4) the process is completed when correction is implemented (implementation); followed by (5) feedback/post-implementation (Kimura 2014), which in some cases can be interpreted as pre-interaction management (Nekvapil–Sherman 2009). The post-implementation phase can be understood both as a reaction to the consequences of prior language management acts and as preparation for further interactions (Fairbrother 2020: 145–148). Norms (expectations) and deviations from them are also key components of the model. They are not part of the management process itself, but can be seen as stage 0, which creates the environment for language situations, for the emergence of problems.

LMT distinguishes between simple and organised language management (Jernudd–Neustupný 1987: 76). In simple language management, speakers manage individual features or aspects of their own or their interlocutor’s discourse “here and now” in a particular interaction. Under this approach, simple language management is performed by the everyday speaker correcting their own language use, the proofreader correcting the spelling of texts, the student looking up a misunderstood term in the dictionary, the crossword puzzler searching for an unknown word, the advertising expert trying to find an effective slogan or the parent advising their child on how to address neighbours.

In LMT’s conception, organised forms of language management include institutional processes such as designation of the language of education, the regulation of normative spelling, the status and role of majority and minority languages and foreign languages, or even management of the linguistic, communicative and socio-cultural situation of multinational companies. According to the LMT approach, organised language management processes are effective when they are based on simple language management processes (Neustupný 1994; Nekvapil 2009). The reason for this is that LMT implements a bottom-up approach whereby any major, comprehensive language management action must be motivated by the needs of speakers (often speaker groups). Therefore, language consulting plays an important role in bridging the gap between simple and organised as well as between micro- and macro-level language management (Kimura–Fairbrother eds. 2020; Beneš et al. 2018).

In the Hungarian speech community, language users are confronted with, and reflect upon, a variety of language problems. Some of these problems cannot be solved in the actual interaction: there are several situations in which language users need information and guidance in assessing and evaluating linguistic phenomena and in considering the characteristics of situational norms (Heltai 2004/2005: 410). Furthermore, professional work on texts, such as translation and proofreading, involves a particular set of language problems that can only be solved through more complex language management processes. In the course of managing language problems, one option is for speakers to contact language consulting services for advice. The broad availability of language consulting services and the high number of speakers who use them clearly demonstrate that such linguistic meta-activities play an important role in managing language problems (Scholze-Stubenrecht 1991: 182; Riegel 2007: 185; Ludányi 2020b, Vranjek Ošlak 2023).

Interactions between speakers and language consultants can be interpreted as language management acts (Beneš et al. 2018: 122–123). The language management cycle can be modelled as follows: first speakers note and evaluate linguistic phenomena that are perceived as problematic or salient (micro-management), then they turn to language consultants to develop or facilitate an adjustment design (macro-management), and finally the speaker has the opportunity to accept and implement, reject, or even partially accept the plan (micro-management) (cf. Nekvapil 2009: 6).

In LMT, the central concept of language consulting is the language problem. Consultants with linguistic expertise are confronted with language problems noted by inquirers and are involved in the process of managing them. Managing problems means developing solutions, but it also goes beyond that, as there are various language problem management strategies (Lanstyák 2018a). Language consulting services may suggest ways to anticipate or avoid language problems in a given type of interaction (Lanstyák 2018a), and in the longer term, it may also contribute to anticipating future problems by collecting and organising inquirers’ language problems in a database and forwarding them to organised forms of language management (Nekvapil–Sherman 2009).

A typical strategy for managing language problems is for the language consultant to advise inquirers by making recommendations that can be applied in everyday practice (Beneš et al. 2018: 122–123). This generally involves sharing in a clear-cut manner the scientific findings which are available on the language issue in question (Beneš et al. 2018; Ludányi 2020a; Ludányi et al. 2022).

As in all discourses about language, in language consulting the presence of language ideologies is inevitable. In institutional language consulting, the ideology of language expertism is necessarily present (Ludányi 2019: 70). This ideology holds that linguists, because of their expertise in linguistics, can guide language users in the appropriate use of language (Lanstyák 2017: 34). In addition, the link between language regulation and power relations is also an essential issue (Gal 2002), as the authority of the institution is a decisive factor in the motivations of inquirers contacting the LCS (see Ludányi et al. 2022 for more details).

The theoretical framework of LMT is particularly effective for analysing language consulting work because the interplay between language management cycles can be used to illustrate how individual language problems can be embedded in larger language planning decisions.

The main research questions of the analysis are:

– How does the LCS contribute to the inclusion of real problems noted by language users in language planning processes?

– How does the position of authority and science inform the operation of the LCS?

– What factors allow the LCS’s activities to be interpreted as organised language management?

The language observations and questions received by the LCS provide research material that reveals a specific segment of speakers’ language problems. The value of this type of data is that it is collected in a non-intrusive way, i.e. it is not created and elicited by research questions but rather noted and reported by the language users themselves (cf. Uhlířová 1997: 83; Beneš et al. 2018). More than 10,000 emails received since 2011, with the number constantly growing thanks to the efforts of the Language Consulting Service, are currently stored by using a structured system of labels. The linguistic material of the emails also undergoes an analysis of metadiscourses that unfold in the process of language consulting, with the aim of exploring language consulting strategies and the assessment and evaluation methods being adopted.

Questions about language use received by the advisory service represent a particular segment of language problems in the community (cf. Uhlířová 1997). A searchable database of nearly 10,000 letters over the past 10 years indicates that language advice is primarily requested in the context of producing texts in formal literacy. In the present study, we highlight some questions in the database that are especially well-suited for illustrating the characteristics, attitudes and practices of the LCS’s work (for more details, see Ludányi et al. 2022; Domonkosi–Ludányi 2024). to address the aforementioned research questions, we build on the characteristics of the services operated by the LCS and present typical language consulting questions and answers as case studies.

The oldest and most traditional institution of language consulting in Hungary is the HUN-REN Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics. Since its foundation, the LCS has been operating at the Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics and its predecessor institution, the Research Institute for Linguistics of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Initially, inquiries about language and spelling were received by postal mail and telephone (for details on the history of the LCS, see Ludányi 2020: 331–336; Heltainé Nagy 2021: 25–31). Telephone language consulting (alongside postal correspondence) was very popular during the first five decades of the LCS. Since 1998, the LCS has also been accepting inquiries by email, and in more than two decades since then, partly due to the decreasing capacity of the telephone service, email has gradually become the main platform for language consulting. Since 2013, in addition to telephone and email advice, the Helyesiras.mta.hu portal’s web tools and resources (see Section 4.1.1) have also assisted users in solving their spelling problems.

The LCS, as a bridge between simple and organised language management, is characterised by the practice of individual inquiries being systematised and labelled by the consultants. As a result of this process, the work of consultants becomes trans-interactional (Nekvapil 2012: 167). The categorisation and primary coding of email inquiries according to types of language problems is performed in parallel with the answering of questions, using a constantly expanding dynamic labelling system. The primary labels are applied to the entire email thread and define the problem type, naming the language or spelling phenomenon in question. The post-processing of emails requires the development of additional coding methods, depending on the problem type, which may also apply to some of the smaller content units of the emails. For example, it is coded when an email describes the context in which the problem was noted (if any, e.g. a dispute), and whether the email contains a specific request for advice, a suggestion or an opinion.

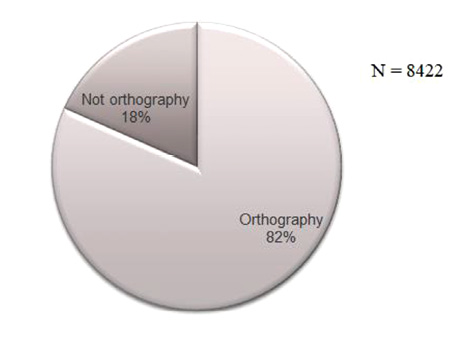

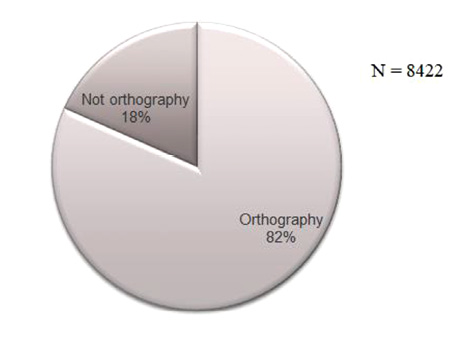

Figure 1 presents the frequency distribution of all emails received between 2012 and 2022. These are prototypical emails requesting language consulting, and do not include emails related to other services (e.g. requests for linguistic proofreading of short public texts, such as commemorative plaques, or for official language expert opinion, which are fee-based services). As the chart shows, more than 80% of the inquiries are related to orthography, which clearly shows that normative spelling is highly prestigious in Hungarian society. The remaining questions mainly concern language use, etymology, the origin and meaning of words and expressions.

As mentioned above, the majority of questions received by the LCS (81% of emails received in 2020) are related to normative spelling. Spelling is a crucial topic of organised language management, as level of conformity to the spelling code strongly determines the perceived adequacy of written texts. Hungarian orthography holds academic status, and currently, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences is responsible for regulating it.

Academic spelling is socially accepted, of central importance to society, non-mandatory but highly prestigious. A significant part of the Hungarian speech community considers academic spelling to be a regulation of essentially unquestionable authority (Beneš et al. [2018: 136–137] describe the same in relation to the Czech speech community). This fact is confirmed by a recent questionnaire survey on the motivations of those who have contacted the LCS.2 The results reveal that the most typical reason for seeking advice has been the prestige of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, the professionalism and credibility of language consultants (Domonkosi–Ludányi forthc.).

For a long time, the basic method for managing an individual’s spelling problems was to consult the latest academic spelling rulebook and dictionaries, and sometimes to consult linguistic experts. With the spread of computers and the development of natural language processing (NLP), however, spell-checkers built into office word-processing programs became increasingly common in the last decade of the 20th century, allowing for immediate proofreading of the text product.

NLP solutions also provide an opportunity to use the experience gathered over decades of LCS work in modern language tools (cf. Hlaváčková et al. 2022). One such tool providing language support is the online spelling advisory portal Helyesiras.mta.hu, launched in 2013, which offers a range of language technology tools and resources (Váradi 2009; Váradi–Ludányi–Kovács 2014) to alleviate the work of language consultants engaged in solving spelling problems that can be answered by using automated methods. The launch and operation of the portal was a conscious, organised language management decision by the HUN-REN Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics. The spelling advisory portal can be used in a variety of simple language management situations when developing an adjustment design, and produces links between language management cycles.

In some cases, the use of the online spelling advisory portal can replace the use of a dictionary or the academic spelling rulebook. Some of the rules of Hungarian normative spelling can be adequately described in a formal language, and turned into algorithms or managed by exception lists. Accordingly, the advisory portal can provide assistance in the following areas of orthography: writing words in one or more words, word-level spell-checking (checking the correctness of certain simple [not compound] words), the spelling of proper names (mainly geographical names), hyphenation, the spelling of numbers and dates, and alphabetisation.

The language management process occurs when the language user encounters a spelling problem (uncertainty about how to spell a word or phrase according to the Hungarian spelling rules) and turns to the spelling advisory portal as an adjustment design. The website is interactive and encourages users to actively engage in the language management process. In particular, the opening page of the website requires users to select the tool that matches their question best from the seven web tools of the portal.

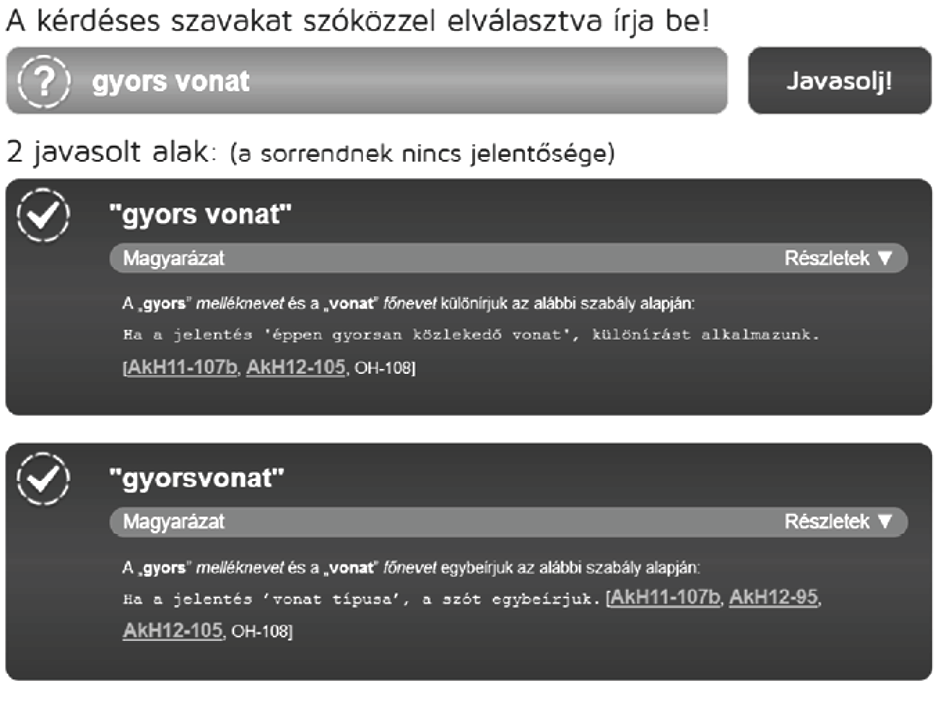

Figure 2 shows one of the tools helping users decide whether words should be written separately or together. In Hungarian, there are terms that can be written separately and together as well, but the two spellings have different meanings. In these cases, the “Separately or together?” tool supplies the user with two solutions to the problem. In addition, it also provides a detailed explanation, referring to the relevant point of the Rules of Hungarian Orthography, which can be displayed by clicking on the “Details” button. Figure 1 presents the web tool’s output for the gyors + vonat ‘fast + train’ input: gyors vonat ‘a train that travels fast’, gyorsvonat ‘a type of train that stops at only a few stations on the railway line’.

In this case, the web tool also relies on the cooperation of the user, who has to choose from the solutions offered which spelling corresponds to the intended meaning of the expression. Sometimes, however, the spelling advisory portal cannot answer the question or the user does not agree with the automatically generated answer, with the result that the language problem has not been solved. In this case, a new language management cycle is started: in most cases, the inquirer contacts the LCS and shares his/her experience of the previous language management cycle. New words and phrases are constantly added to the portal database based on user feedback, which again helps bridge the gap between simple and organised language management.

As mentioned earlier, there are also more complex problems that cannot be managed simply by using the online spelling advisory portal. Examples for this include cases when (1) the spelling rule is very complicated, a sub-case of which is when the inquirers contact the LCS about the spelling of specialised languages (e.g. chemistry), (2) contradictory rules and principles exist in the system of Hungarian orthography itself, and (3) the problem results from the lack of spelling codification (e.g. when new phenomena are named or a loanword has just been borrowed from a foreign language).

In case (1), it is the practice of the LCS to explain the spelling norm or rule carefully while also accommodating the inquirer’s point of view (cf. Vranjek Ošlak 2023: 159–162). In some cases, the inquirer is redirected to the relevant committee or specialist. In case (2), when there are conflicting spelling rules and principles (cf. Vranjek Ošlak 2023: 162–164), the LCS explicitly acknowledges the contradictions and usually offers the inquirer several solutions. In case (3), when the source of spelling problems is the constant emergence of new realia and new names, the LCS solution is to try to find analogies, examine spelling practice based on corpora, and suggest spelling forms following the principles of the Rules of Hungarian Orthography (cf. Vranjek Ošlak 2023: 166–167).

One of the most common ways to increase vocabulary is to borrow words from foreign languages. In Hungarian orthography, the spelling of loanwords can be of three types: (1) spelling that follows the spelling of the source language (e.g. déjà vu, couchette, flow), (2) spelling according to Hungarian pronunciation, (pl. randevú [< rendez-vous ‘an arranged date’], lájkol ‘to like’, szelfi ‘selfie’, and (3) alternate spelling or spelling variations in the dictionary (e-mail ~ ímél, chat ~ cset). There are examples for all three types in spelling dictionaries. What causes a language problem for speakers is when newly borrowed neologisms do not yet have a codified spelling; hence, dictionaries and the spelling advisory portal cannot provide any support in developing an adjustment design. In these cases, it is also clear that the authority and the role of the institution in codification is the reason why the LCS is contacted by the inquirers. Less frequently, the inquirer may also reflect on the spelling of a loanword that already has a codified spelling, asking the LCS to clarify the reason for the codification decision. However, such inquiries already show a speaker attitude that takes less account of authority (cf. Kopecký 2022).

The following two practical examples illustrate the problem-solving practices of the LCS.

One inquirer asked the LCS for advice on the spelling of the term déjà vu. In his email, he explained his preliminary adjustment design in detail and looked up the relevant points in the academic spelling rulebook, pointing out the inconsistency of the rules. One of the rules says that commonly used foreign words borrowed from Latin-script languages are usually spelled according to the Hungarian pronunciation, while another says that words which are less frequently used are usually spelled according to the spelling rules of the source language. The inquirer pointed out the contradictory nature of spelling the term randevú according to the Hungarian pronunciation but not the equally common and widespread déjà vu. In response, the LCS staff member explained that there is no general rule for the spelling of words borrowed from foreign languages, each case having to be examined individually, based on a number of criteria. As the respondent highlighted, frequency, prevalence, and “how much the term is perceived as Hungarian” by the language users are important criteria, but other aspects may also play a role (common spelling practice, the word’s participation in inflectional and derivational patterns of Hungarian morphology, the desire for simplicity, and so on). The same aspects are taken into account by the LCS in cases where the inquirers are interested in the normative spelling of loanwords which, because of their novelty, have not yet been codified.

Inconsistencies in spelling codification were also the cause of the spelling problem in a letter written by an editor of the Hungarian Wikipedia, reporting on an editorial dispute about the Wikipedia article on the bird fakusz ~ fakúsz ‘treecreeper’.3 The inquirer asked the LCS to clarify whether the spelling fakusz (with u) or fakúsz (with ú)4 should be used in the Wikipedia article. The inquirer and his fellow editors recognised the contradictory nature of the spelling, i.e. they discovered that while academic publications of codifying value (spelling and monolingual explanatory dictionaries) use the fakúsz spelling, in the ornithological literature fakusz is also considered common. In her reply, the LCS expert confirmed the problematic nature of the spelling on the basis of the dictionary and corpus data available to her, and suggested that the Wikipedia article should definitely mention this ambiguity in spelling. A solution was proposed which included the variants in parentheses after the heading, e.g. fakusz [u or ú], and the other variant in parentheses: fakusz (or fakúsz). Although the inquirers had contacted the LCS as a norm authority, they appreciated its balanced response which acknowledged spelling variability and rule ambiguity. This case indicates a reconsideration of the role of language consultants: the inquirers contacted the LCS, knowing the codification work, shared the full text of the debate including arguments and counter-arguments, and decided on the spelling to be used after a dialogue and collective discussion.

The interplay between organised and simple language management processes is also shown by the fact that some inquirers seek to know the reason for the codified, normative spelling of a given word. The LCS is also responsible for collecting of uncodified and/or controversial phenomena and areas of Hungarian orthography. Bridging the gap between simple and organised language management processes (Kimura–Fairbrother eds. 2020), it provides this type of data to the committee responsible for the management of academic spelling regulations.

The main types of questions related to language use concern the following areas: the naming of new phenomena and new terms; finding the Hungarian equivalent of foreign words and expressions; word variants; the existence of words; finding the meaning of words; philological questions about academic texts; questions on pronunciation; questions related to linguistic politeness, in particular in the area of address forms (e.g. how to address unknown women in emails); suggestions for “introducing” new words; conscious creation of new words; language superstitions; and etymological issues.

In the language management cycle, every language use issue is a noted language problem that speakers have not been able to solve satisfactorily in a given communication situation. The data suggest that speakers primarily contact the LCS with language problems noted when producing normative, formal, written language texts. The production of formal written language texts is a situation that extends beyond simple language management: the inquirers expect the LCS to serve as a normative authority in charge of producing an adjustment design.

A recurring type of emails asks for guidance on the correctness or incorrectness of a variant, indicating a strong influence of the standard ideology according to which linguistic variants can be inherently judged in terms of correctness (cf. Andersson 2000; Milroy 2006). For questions asking about general correctness, it is very important to point out in the answer that the use of each variant varies historically and that its current use depends on various socio-cultural factors. In most cases, the inquirer is informed not only about the fact that both variants exist and are accepted in linguistic practice, but also about the distribution and functions of the variants.

The correctness of linguistic variables was also questioned, for example, by an inquirer who asked about the use of the forms zászlója/zászlaja (the third person singular possessive form of zászló ‘flag’). In this case, spelling manuals and glossaries (Laczkó–Mártonfi 2004) can provide clear information that both forms are widely used.

Differences in style and nuances of meaning between specific variants can also be indicated partly on the basis of dictionary data. According to data from the Explanatory Dictionary of Hungarian (Bárczi–Országh eds. 1959–1962), the variant zászlaja is rather old-fashioned and more sophisticated in style.

Corpus data are also commonly used to map the usage distribution of problematic variables in language consulting. In the case at hand, the Hungarian Gigaword Corpus (Oravecz–Váradi–Sass 2014) revealed that the zászlaja form tends to occur in abstract senses and in phrases (e.g. beáll valaki/valami zászlaja alá ‘stand under someone’s flag’ = ‘join in someone’s goals or ideas’) and is often used in solemn contexts. In addition to offering data-based information on stylistic value, the language consultant also seeks to provide a historical linguistic explanation. Accordingly, the consultant’s answer shows that there are several variants of certain lemmas in Hungarian. This means that in addition to the main form, i.e. the dictionary form (here, zászló), the lemma has one or more alternative stems (here, zászla-) which appear before certain suffixes.

In their responses, LCS’s linguists strive to make precise references to the sources and data collection procedures used. This is important for the language management process: by explaining the methods of adjustment design and by indicating sources and their availability, LCS workers also intend to influence simple everyday micro-management processes (Kimura–Fairbrother eds. 2020). Interpreting the responses of the LCS in the context of the language management cycle, it is worth observing at this point that the LCS, in its responses to language use, attempts to address language problems not by referring to authority but by building on real language data. Adjustment designs are developed by taking into account the language situation and its broader context, relying on available language data.

As well as presenting the data in a clear and concise way, part of the LCS’s language consulting strategy is to make a clear and explicit suggestion wherever possible. In the case of zászlója/zászlaja, however, the reply did not indicate a preference for either of the variants but rather, by clearly distinguishing between their ranges of use and stylistic values, gave the inquirer the opportunity to choose the variant he/she considered appropriate. In such cases, the LCS does not settle the language problem but shows the linguistic role of the different options.

Some of the language problems of speakers are caused by different attitudes to language change. This can be illustrated by a problem concerning the verb centíroz/centríroz ’to center’, which was submitted to the LCS in the wake of an emerging debate about the correctness and appropriateness of the two variants. The inquirer reported that a recent book on bicycle fitting had been published under the title “Biciklikerék fűzése, centírozása és egyéb munkálatai” (‘Bicycle wheel lacing, centering and other work’) and received much criticism in a professional Facebook group on the basis that centrírozás ‘centering’ was the correct form of the word in the title.

The inquirer had consulted various specialist dictionaries and even the spelling advisory portal presented in this study before contacting the LCS. Both forms were present in the resources, but there was no information on when and in which situation to use them. The inquirer was aware of the original form of the verb (centríroz) but also of the widespread use of the newer form with a consonant gap (centíroz), and therefore wanted to know whether the newer form was also acceptable.

To manage the problem, LCS experts used dictionary data to confirm that both variants were correct but also sought to highlight their differences in social meaning and stylistic value. Based on corpus data and a study of texts on bicycle and car mechanics, the consultants found that the newer form centíroz is a frequent and accepted variant, and it is even common among vehicle technicians. However, they also mentioned in their response that, motivated by their aim to identify the origin of words and the ideology of linguistic originalism (Lanstyák 2018b), language usage manuals (Grétsy–Kemény 2005: 89) and normative spelling dictionaries (e.g. Tóth eds. 2017: 76) consider only the original variant centríroz to be correct. The difference in social meaning between the two variants is therefore that the original form centríroz shows a more conservative attitude, which prefers to preserve the original form and is less flexible in the face of linguistic changes, while the newer form centíroz shows an attitude more adapted to the actual use of technical language.

This led the LCS consultants to formulate a very nuanced piece of advice. It was suggested that the original form centríroz might be more appropriate when addressing a linguistically more conservative audience, and the newer form centíroz might be preferable when addressing the professional bicycle and car mechanic communities.

In managing the language problem in question, LCS experts thus built on available data as well as on the practices and needs of speakers, treating the linguistic norm in a flexible way. The development of the adjustment design gave clear evidence of ideological awareness on the part of the actors of organised language management (Nekvapil 2012: 167). The consultants did not simply align language use to a norm but developed a multi-output adjustment design that accommodated language user attitudes and ideologies. Interpreted in the context of the language management cycle, this language problem is partially persisting. Since the dictionary records both variants, the different social meanings of the variants create a situation that maintains a recurrent language problem in the speech community.

Another important type of questions in the email database is when speakers ask the LCS about the use of new terms. These questions indicate the process of a stylistic differentiation of the standard (Havránek 1932/1983) and the expansion of terminologies (Chiu–Jernudd 2001; Lanstyák 2019). Answering such questions requires careful consideration, and language consultants do their best to take into account basic aspects of terminology. From the point of view of LMT, terminological problems necessarily require collective activity and the consensus of a professional community, i.e. they cannot be resolved in the interaction itself.

The complexity of managing terminological problems can be demonstrated by a letter requesting the LCS’s opinion on whether the term közösségi közlekedés (‘public transport’, literally ‘community transport’) can be used in Hungarian as an appropriate synonym for tömegközlekedés (‘public transport’, literally ’mass transport’). The problem for the inquirer was that the adjective közösségi ‘community, social’ has a meaning ‘from the bottom up, community-run (without state intervention)’ (e.g. közösségi média ’social media’, közösségi finanszírozás ’social finance’), which does not apply to ‘public transport’.

In this case, the LCS experts informed the inquirer about the history of the term’s development. They noted that the replacement of the term tömegközlekedés by közösségi közlekedés was a conscious business and language policy decision by transport companies in the late 1990s, prompted by negative connotations of the word tömeg ‘mass’, which brought to mind the crowding of vehicles.

In the process of managing this problem, due credit was given to the inquirer for correctly observing that using the word közösségi ’community’ leads to terminological ambiguity, since there are indeed community-run transport options. Despite this terminological contradiction, the role of usage is decisive in the spread of the term, and the decision of transport companies plays a key role in this, as it also has a fundamental impact on everyday linguistic practice. In this situation, the LCS consultants did not solve the problem but rather provided the inquirer with an analysis of the complexity of terminology management.

Real language problems of a community can be identified by observing language problems experienced by the speakers themselves. This is the reason why organised language management processes are effective only when they can be traced back to simple language management processes (Neustupný 1994; Nekvapil 2009). The primary task of language consulting services is to manage individual language problems. However, their activity extends well beyond the solution of particular situations by pointing to typical problems, allowing problems to be collected and categorised, and facilitating the incorporation of solutions into language use tools, dictionaries, and spelling lists.

A closer look at the work of the LCS shows that the solutions proposed depend on the type of language problem, the context of the problem and the inquirer’s intentions and preconceptions. The aim of language consulting is to offer advice by taking into account the socio-cultural situation and the interpretative framework of the inquirer. Linguistic recommendations are always based on knowledge of linguistic background and the relevant research findings. Depending on the type of question, it may also be necessary to use language guidebooks, dictionaries or corpora. The LCS also performs data collection and data systematisation tasks. The data obtained through the categorisation and processing of questions can be fed back into the development of language guidebooks and writing assistants.

The practice of institutional language consulting thus provides an opportunity to establish a connection between speakers’ everyday language problems and organised language management, bridging the gap between simple and organised, micro- and macro-level language management (Kimura–Fairbrother eds. 2020).

An analysis of LCS practices in relation to the first research question (see Section 3) shows that language problems noted by language users are processed by the LCS staff and play a role in subsequent stages of codification. Furthermore, they are integrated into the language guidebooks and the database of the spelling advisory portal Helyesiras.mta.hu, so that the work of the LCS indeed creates an active link between simple and organised language management processes.

With regard to the second research question, it can be concluded that inquirers typically contact the LCS because of the prestige of the institution. For questions on words with codified spellings, consultants also provide answers based on the authority of the norm (but in a flexible manner that takes into account the inquirer’s perspective). When developing adjustment designs for spelling questions on words without a codified spelling or for language use questions, consultants strive to rely on linguistic data and research while engaging in an open dialogue with the inquirer. The LCS has the option of engaging in a dialogue with the inquirers as equal partners rather than giving advice from a position of power based on the authority (cf. Gal 2006; Kopecký 2022).

In relation to the third research question, the analysis has shown that the LCS also displays features of organised language management. First, language management acts are trans-interactional, as inquirers initiate dialogue about linguistic experiences that they had in other interactions. Second, the LCS is linked to the institutional background of language and spelling codification (cf. Vranjek Ošlak 2023). It is responsible for identifying uncodified and/or controversial phenomena and areas of Hungarian orthography, serving as a connection between simple and organised language management processes (cf. Kimura–Fairbrother eds. 2020). It also provides this data to the committee responsible for managing academic spelling regulations. Third, the activity of the LCS has a theoretical basis. Finally, the consultants are conscious of what they do and the language ideologies behind their work.

Andersson, L-G. 2000. Language cultivation in Sweden. In K. Sándor (ed.) Issues on Language Cultivation. Szeged: JGyF Kiadó. 85–98.

Bárczi, G., L. Országh (eds.) 1959–1962. A magyar nyelv értelmező szótára [The Explanatory Dictionary of the Hungarian Language ]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Beneš, M., M. Prošek, K. Smejkalová, V. Štěpánová 2018. Interaction between language users and a language consulting center: Challenges for language management theory research. L. Fairbrother, J. Nekvapil, M. Sloboda (eds.). The language management approach: A focus on research methodology. Berlin: Peter Lang. 119–140.

Chiu, A., B. H. Jernudd 2001. Chinese IT terminology management in Hong Kong. TermNet News, 72 (73), 2–10.

Domonkosi, Á., Ludányi, Zs. 2024. Language consulting in Hungary: a case study on the practices of the Hungarian Language Consulting Service. In press.

Domonkosi, Á., Zs. Ludányi forthc. Kik és miért kérnek nyelvi tanácsot? A nyelvi tanácsadó szolgálathoz fordulók motivációnak kérdőíves vizsgálata [Questionnaire survey of the motivation of people who contact the Hungarian Language Consulting Service].

Fairbrother, L. 2020. Diverging and intersecting management. G. C. Kimura, L. Fairbrother (eds): A Language Management Approach to Language Problems: Integrating Macro and Micro Dimensions. Amsterdam – Philadelphia: John Benjamins. 133–156.

Gal, S. 2006. Contradictions of standard language in Europe: Implications for the study of practices and publics. Social Anthropology 14 (2), 163–181.

Grétsy, L., M. Kovalovszky (eds.) 1980–1985. Nyelvművelő kézikönyv [Handbook of Language Cultivation]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Grétsy, L., G. Kemény (eds.) 2005. Nyelvművelő kéziszótár [Dictionary of Language Cultivation]. Budapest: Tinta Könyvkiadó.

Havránek, B. 1983. The functional differentiation of the standard language. Praguiana. Some basic and less known aspects of the Prague linguistic School. J. Vachek (ed.). Prague/Amsterdam. 143–164. (Originally published in Czech in Spisovný jazyk a jazyková kultura, Praha, 1932.)

Hlaváčková, D., H. Žižková, K. Dvořáková, M. Pravdová 2022. Developing Online Czech Proofreader Tool: Achievements, Limitations and Pitfalls. Bohemistyka 1, 122–134. https://doi.org/10.14746/bo.2022.1.7

Heltai, P. 2004/2005. A fordító és a nyelvi normák [Translation and language norm] I., II., III. Magyar Nyelvőr 128 (4), 407–434., 129 (1), 31–58.; 129 (2), 165–172.

Heltainé Nagy, E. 2021. Nyelvművelés és nyelvi tanácsadás. Vázlatos áttekintés a hetvenes évek közepétől máig [Language cultivation and language consulting. An overview from the mid-seventies to the present]. A korpusznyelvészettől a neurális hálókig: Köszöntő kötet Váradi Tamás 70. születésnapjára. R. Dodé, Zs. Ludányi (eds.). Budapest: Nyelvtudományi Kutatóközpont. 24–33.

Jernudd, B. H. 1991. Individual discourse management (the 5th lecture). Lectures on Language Problems. Delhi: Bahri Publications.

Jernudd, B. 2018. Questions submitted to two language cultivation agencies in Sweden. The language management approach: A focus on research methodology. L. Fairbrother, J. Nekvapil, M. Sloboda (eds.). Berlin: Peter Lang. 101–117.

Jernudd, B. H., Neustupný, J. V. 1987. Language planning: for whom? Proceedings of the International Colloquium on Language Planning. L. Laforge (ed.). Québec: Les Press de L´Université Laval. 69–84.

Kimura, G. C. 2014. Language management as a cyclical process: A case study on prohibiting Sorbian in the workplace. Slovo a slovesnost 75 (4), 255–270.

Kimura, G. C., L. Fairbrother (eds.) 2020. A language management approach to language problems: Integrating macro and micro perspectives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Kopecký, J. 2022. Divergent interests and argumentation in Czech Language Consulting Center interactions. Interests and Power in Language Management. M. Nekula, T. Sherman, H. Zawiszová (eds.). Berlin: Peter Lang. 73–99.

Laczkó, K., A. Mártonfi 2004. Helyesírás [Orthography]. Budapest: Osiris Kiadó.

Lanstyák, I. 2017. Nyelvi ideológiák (általános tudnivalók és fogalomtár) [Language ideologies (general information and glossary)]. http://web.unideb.hu/~tkis/li_nyelvideologiai_fogalomtar2.pdf [Accessed: 31/01/2023.]

Lanstyák, I. 2018a. On the strategies of managing language problems. The language management approach: A focus on research methodology. L. Fairbrother, J. Nekvapil, M. Sloboda (eds.). Berlin: Peter Lang. 67–97.

Lanstyák I. 2018b. Nyelvi originalizmus a szavak hangalakjának nyelvhelyességi megítélésében [Linguistic originalism in assessments of what is the correct pronunciation of words]. Nova Posoniensia VIII. A pozsonyi magyar tanszék évkönyve / Zborník Katedry maďarského jazyka a literatúry FiF UK. K. Misad, Z. Csehy (eds.). Bratislava: Szenczi Molnár Albert Egyesület. 7–34.

Lanstyák, I. 2019. Nyelvmenedzselés-elmélet és terminológia [Language Management Theory and terminology]. Terminológiastratégiai kihívások a magyar nyelvterületen. Á. Fóris, A. Bölcskei (eds.). Budapest: L’Harmattan, Országos Fordító és Fordításhitelesítő Iroda. 73–93.

Lengar Verovnik, T., H. Dobrovoljc 2022. Revision of Slovenian Normative Guide: Scientific Basis and Inclusion of the Public. Slovene Linguistic Studies 14, 183–205. https://doi.org/10.3986/sjsls.14.1.07

Ludányi, Zs. 2019. Language ideologies in Hungarian language counselling interactions. Eruditio – Educatio 14 (3), 59–76.

Ludányi, Zs. 2020a. Nyelvi menedzselés és nyelvi tanácsadás. Helyzetkép, lehetőségek, feladatok [Language management and language consulting: Situation report, possibilities, and tasks]. Magyar Nyelvőr 144 (3), 318–345.

Ludányi, Zs. 2020b. Language consulting: A brief European overview. Eruditio – Educatio 15 (3), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.36007/eruedu.2020.3.025-047

Ludányi, Zs., Á. Domonkosi, Á. Kocsis, D. Jakab 2022. A nyelvi menedzselés szemlélete és a nyelvi tanácsadás [The language management approach and language consulting.]. Tanulmányok a nyelvészet alkalmazásainak területéről. A. Deme, Á. Kuna (eds.). Budapest: ELTE Eötvös Kiadó. 73–107.

Milroy, J. 2006. The Ideology of the Standard Language. The Routledge companion to sociolinguistics. C. Llamas, L. Mullany, P. Stockwell (eds.). London: Taylor, Francis Group. 133–139.

Nekula, M., T. Sherman, H. Zawiszová (eds.) 2022. Interests and Power in Language Management. Berlin: Peter Lang.

Nekvapil, J. 2009. The integrative potential of Language Management Theory. Language Management in Contact Situations: Perspectives from Three Continents. J. Nekvapil, T. Sherman (eds.). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. 1–11.

Nekvapil, J. 2012. Some thoughts on “noting” in language management theory and beyond. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication 22 (2), 160–173.

Nekvapil, J., Sherman, T. 2009. Pre-interaction management in multinational companies in Central Europe. Current Issues in Language Planning 10, 181–198.

Nekvapil, J., Sherman, T. 2015. An introduction: Language Management Theory in Language Policy and Planning. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 232, 1–12.

Neustupný, J. V. 1994. Problems of English contact discourse and language planning. English and Language Planning. T. Kandiah, J. Kwan-Terry (eds.). Singapore: Academic Press. 50–69.

Oravecz, Cs., Váradi, T., Sass, B. 2014. The Hungarian Gigaword Corpus. Proceedings of Ninth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2014). N. Calzoari, K. Choukri, T. Declerck, H. Loftsson, B. Maegaard, J. Mariani, A. Moreno, J. Odijk, S. Piperidis (eds.). Reykjavik: European Language Resources Association. 1719–1723.

Riegel, M. 2007. Sprachberatung im Kontext von Sprachpflege und im Verhältnis zu Nachslagewerken. Unter besonderer Beachtung der Sprachberatungsstelle des Wissen Media Verlages. Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philologischen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br.

Scholze-Stubenrecht, W. 1991. Die Sprachberatungsstelle der Dudenredaktion. Deutsche Sprache 19 (2), 178–182.

Tóth, E. (eds.) 2017. Magyar helyesírási szótár. [Hungarian spelling dictionary]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Uhlířová, L. 1997. “Language service” is also a service for linguistics. Linguistica Pragensia (2), 82–90.

Váradi, T. 2009. Bringing language technology to the masses. Some thoughts on the Hungarian online spelling dictionary project. After half a century of Slavonic natural language processing. D. Hlaváčková, A. Horák, K. Osolsobě, P. Rychlý (eds.). Brno: Tribun EU. 227–230.

Váradi, T., Zs. Ludányi, R. Kovács 2014. Géppel segített helyesírás. A helyesiras.mta.hu portál készítéséről [Computer aided spelling advice. Designing the helyesiras.mta.hu site]. Modern Nyelvoktatás 20 (1–2), 43–58.

Vranjek Ošlak, U. 2023. Language counselling: Bridging the gap between codification and language use. Eesti ja Soome-Ugri Keeleteaduse Ajakiri 14 (1), 149–173. https://doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2023.14.1.05

1 Research Institutes in Hungary, including the Research Institute for Linguistics were under the supervision of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences until 2019, when they were brought by a governmental decree under the supervision of Eötvös Loránd Research Network. Following a new organisational change, the official name of the institution from 12 March 2021 is Hungarian Research Centre for Linguistics. From 1 September 2023, the name of the research network changed to Hungarian Research Network, abbreviated HUN-REN.

2 A similar questionnaire survey is reported by a Slovenian language advisory service (Lengar Verovnik–Dobrovoljc 2022: 197–198).

3 The treecreepers are a family, Certhiidae, of small passerine birds, widespread in wooded regions of the Northern Hemisphere and Sub-Saharan Africa.

4 In Hungarian spelling, the letter u corresponds to the short close back rounded vowel /u/, and ú corresponds to the long close back rounded vowel /u:/.