Problemos ISSN 1392-1126 eISSN 2424-6158

2024, vol. 106, pp. 22–35 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Problemos.2024.106.2

Lianchong Deng

School of Philosophy

Zhejiang University, China

Email dlchong@zju.edu.cn

ORCID https://orcid.org/0009-0000-8700-2196

Abstract. Leisure is both a necessary precondition for, and the ultimate purpose of, human activities. As such, it is commonly understood as a state of contemplation practiced for its own sake. However, this view raises a problem regarding its universal accessibility. Aristotle’s ethical and political theories demand leisure as a universally embraced way of life, while contemplative leisure appears impractical for common people. There are broadly two approaches to fix this problem: (a) distinguishing leisure of two sorts, and (b) expanding the semantic scope of contemplation. Nevertheless, they both come with certain limitations. I propose redefining leisure as a moral-psychological concept aligned with the allegedly hexis-state of the soul. This redefinition presents leisure as a basic human condition, offering a possible solution to the problem of its universal accessibility.

Keywords: Aristotle, Leisure, Soul, Moral psychology

Santrauka. Laisvalaikis yra ne tik žmogiškųjų veiklų būtinoji sąlyga, bet ir galutinis jų tikslas. Jis įprastai suvokiamas kaip savitikslė kontempliacijos būsena. Tačiau toks požiūris iškelia klausimą apie visuotinį laisvalaikio prieinamumą. Aristotelio etinės ir politinės teorijos reikalauja, kad laisvalaikis būtų laikomas visuotinai praktikuojamu gyvenimo būdu, tačiau paprastiems žmonėms kontempliatyvusis laisvalaikis atrodo nepraktiškas. Šią problemą galima spręsti iš esmės dviem požiūriais: (a) laisvalaikyje įžvelgiant dvi rūšis arba (b) praplečiant semantinę laisvalaikio sąvokos aprėptį. Tačiau abu šie požiūriai susiduria su tam tikromis problemomis. Siūlau naujai apibrėžti laisvalaikį kaip moralinę-psichologinę sąvoką, derančią su prielaidaujama sielos hexis būsena. Pagal tokį apibrėžimą laisvalaikis būtų traktuojamas kaip kertinė žmogiškoji būklė, atverianti galimybę spręsti visuotinio laisvalaikio prieinamumo problemą.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: Aristotelis, laisvalaikis, siela, moralės psichologija

__________

Acknowledgement. I am grateful to the participants of the work-in-progress series (WIPS) for their insightful feedback on the earlier drafts of this paper. Many thanks to the anonymous referees for their valuable comments.

This article was supported by the Major Program of the National Social Science Fund of China, ‘Research on Mediterranean Civilization and the Origins of Ancient Greek Philosophy’ (23&ZD239)

Received: 19/06/2024. Accepted: 16/09/2024

Copyright © Lianchong Deng, 2024. Published by Vilnius University Press.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

In Nicomachean Ethics (EN) X 7, 1177b19–22, Aristotle asserts that leisure, in the strictest sense, is accessible only to those capable of contemplation, presumably philosophers. However, in Politics (Pol.) VII 3, 1325b30–33, Aristotle presents a broader view of leisure’s accessibility. He argues that “people as a whole in the city-state,” analogous to “each individual person,” can attain the best life, which is typically characterized by a leisurely lifestyle. This creates a dilemmatic problem regarding the universal accessibility of leisure. The contemplative reading of leisure leaves no room for common people, thereby inevitably posing an inconsistency within Aristotle’s philosophical framework. Conversely, as soon as the inclusive interpretation of leisure is taken in consideration, leisure’s strict essence risks to collapse. Failure to reconcile these conflicting perspectives would reveal a potential flaw in Aristotle’s accounts of leisure.

In response, I plan to provide a moral-psychological explanation of leisure, thereby documenting an inherent justification of its universal accessibility in Aristotle’s philosophy. First, I will elucidate the intricate connection among leisure, purpose, and contemplation, thereby clarifying why leisure is often linked with the contemplative lifestyle. Next, I will delve into the problem of universal accessibility in leisure that arises from this understanding, and critically examine the two proposed solutions to this issue. I will then present an alternative interpretation of leisure, redefining it as a fundamental condition deeply rooted in human nature. Through this fresh perspective, I will conclude that leisure is not exclusively reserved for contemplators, but also accessible to common people.

In Metaphysics (Metaph.) A 1–2, Aristotle characterizes a natural cognitive progression that begins with perception, advances through experience and craft knowledge, and culminates in wisdom. Aristotle posits that while all animals have perceptual capacities, only humans can grasp the unity among diverse empirical phenomena. This capacity arises from the accumulation of experience through repeated exposure to individual perceptions. Experience enables humans to discern the causes of individual entities. By contrast, craft knowledge reveals the causes of a specific kind of entities, thus establishing a deeper connection to their essence than mere experience. Importantly, craft knowledge remains confined to understanding particular causes, whereas wisdom can comprehend the first causes of everything. Throughout his exploration of human cognition, Aristotle finally underscores the socio-psychological preconditions necessary for attaining wisdom, namely, leisure:

Hence, when all such [i.e. practical] crafts were already developed, the knowledges that aim neither at pleasure nor at necessities were discovered, first in the places where people had leisure [ἐσχόλασαν]. (Metaph. A 1, 981b20–23)1

People who have leisure, according to Aristotle, are freed from the constraints of life’s necessities. This freedom grants them the privilege to engage in purely intellectual activities, which allows them to transcend the conventional perspectives on reality and attain wisdom through a sense of wonder (Metaph. A 2, 982b11–28). This idea can be viewed as an epistemological statement, advocating leisure as an essential precondition for intellectual pursuits which lead to philosophical knowledge.

Additionally, Aristotle makes a parallel claim in the political realm. He argues that leisure is imperative for engagement in political affairs, especially for high-level public officials like rulers and generals. Having leisure would mean that they have adequate financial resources, which effectively shields them from bribery attempts and enables them to maintain integrity and independence in their duties (Pol. II 11, 1273a32–37). Moreover, Aristotle contends that leisure is a prerequisite for obtaining citizenship, as individuals consumed by daily survival struggles lack the focus necessary for engagement in public affairs (Pol. II 9, 1169a34–36). Conversely, those without leisure – like farmers, merchants, retailers, and unskilled laborers – are excluded from political offices due to their reliance on daily labor (Pol. IV 4, 1291a5–b25, IV 6, 1292b25–26). Therefore, it seems that leisure emerges as a crucial precondition for individuals to attain the political subject status defined by Aristotle.

The preceding analysis highlights leisure as an indispensable precondition for both intellectual and political pursuits. According to Aristotle’s theory of conditional or hypothetical necessity, certain preconditions are necessarily present if the desired purpose is to be achieved.2 Hence, leisure embodies the normative implications, serving as a necessary requirement for individuals committed to the quest for human excellence. Without leisure, individuals may be hindered from actualizing their intellectual and political potential, thereby impeding their flourishment. However, while viewing leisure as a necessary precondition for achieving human excellence is persuasive, it is more than this.3 This is because leisure also encompasses an additional dimension, specifically, the purpose one strives to achieve.

At the beginning of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle establishes a fundamental connection among purpose, the good, and happiness. From his perspective, human behaviors and decisions are intrinsically motivated by the pursuit of the good, which serves as the central purpose of human life. Furthermore, Aristotle argues that the highest good is identical with happiness (EN I 1, 1094a1–2, I 4, 1095a15–18). Subsequently, Aristotle highlights the close relationship between leisure and happiness. He firmly asserts that individuals constantly occupied with necessities cannot attain happiness because, as he states, “happiness exists in leisure [ἡ εὐδαιμονία ἐν τῇ σχολῇ εἶναι]” (EN X 7, 1177b4). Given his belief that leisure is ‘in itself [αὐτὸ]’ equivalent to happiness (Pol. VIII 3, 1338a1–2), it is plausible to conceive leisure as an instantiation of, or even identical with, his ideal concept of happiness. In this manner, Aristotle orients human purpose as having a leisure lifestyle, as expressed in the well-known ‘slogan’: “We are busy for the sake of leisure” (EN X 7, 1177b4–5; cf. Pol. VII 14, 1333a30–32, VII 15, 1334a14–16, VIII 3, 1337b29–32).

Leisure implies freedom from life’s basic requirements, serving as a necessary precondition for intellectual and political engagement. Moreover, it embodies the very essence of happiness and holds the status of the ultimate human purpose. Therefore, it is clear that leisure exhibits a dual nature. On the one hand, it functions as a precondition for achieving the purpose of human life; on the other hand, it constitutes the purpose itself. In other words, leisure activity is practiced purely for its own sake. Aristotle illustrates this dual nature of leisure by contrasting it with political and military activities:

If among actions in accordance with virtues, political and military actions are distinguished by nobility and greatness, and these are lacking leisure [ἄσχολοι] and aim at some purpose [τέλους τινὸς] and are not desirable for their own sake [δι’ αὑτὰς]. (EN X 7, 1177b16–18; cf. EN X 7, 1177b7–13)

Aristotle critiques political and military affairs for their lack of leisure, as they are not desired and practiced for their own sake. Politicians, for instance, are often driven by the pursuit of power and influence rather than the inherent value of political actions. Similarly, generals involve in warfare not for the military activity itself, but for economic and geopolitical interests. Thus, these political and military pursuits are oriented toward external purposes, trapped in the cycle of “for the sake of something [ἕνεκα τινος]” (Pol. VIII 3, 1338a4). This hinders them from regarding practical activities as purposes in themselves, leading to the endless pursuit of power, conquest, and profit. The role of leisure, according to Aristotle, is to liberate individuals from the constraints of means-purpose chains, enabling them to appreciate the intrinsic value of things. By engaging in leisure, human practices become self-contained, no longer merely serving as instrumental preconditions for achieving higher purposes.

The Nicomachean Ethics begins with the same concerns of terminating the endless means-purpose chains in the practical realm. Aristotle observes that human activities inherently pursue specific purposes. If these pursuits expand indefinitely without an ultimate purpose, human desires would become empty and vain – which he strongly opposes. To address this issue, Aristotle proposes identifying a particular type of activity practiced “for its own sake [δι’ αὑτὸ]” (EN I 2, 1094a19). This activity not only serves as the purpose for other practical activities but also constitutes the purpose in itself. Engaging in this self-sufficient, intrinsically valuable activity provides individuals with a sense of completion, effectively stopping their relentless pursuits of external purposes (EN I 2, 1094a18–22). Now, a pertinent question arises: What kind of activity is worth practicing for its own sake, not for further purposes? Aristotle provides his answer at the end of this book:

This activity [i.e. contemplation] alone would seem to be desired for its own sake [δι’ αὑτὴν]; for nothing arises from it apart from the contemplating, while from other practical activities we gain more or less apart from the action. (EN X 7, 1177b1–4; cf. EN X 7, 1177b19–20; Pol. VII 3, 1325b18–21)

According to Aristotle, the only activity possessing intrinsic value and worthy of practicing for its own sake is contemplation.4 This perspective allows us to view contemplation as a concrete instantiation of the leisure state. Notably, Aristotle’s other accounts provide direct evidence for this view. In EN X 7, 1177b19–25, he explicitly asserts that leisure for humans is undeniably linked with ‘contemplative activity [θεωρητικὴ]’. Similarly, in Pol. VII 15, 1334a23, he associates leisure with ‘philosophy [φιλοσοφίας]’, which employs contemplation to investigate causes and principles. In essence, Leisure is predominantly understood as contemplative leisure, typically accessible only to a select few, namely, philosophers. This belief aligns with Aristotle’s philosophical system and has been widely recognized by mainstream scholarship.5

The assertion that leisure is strongly associated with contemplation remains a subject of debate. One immediate challenge lies in the problem of universal accessibility in leisure. Aristotle argues for the superiority of contemplation, by emphasizing its superlative continuity, self-sufficiency, and distinct pleasure (EN X 7, 1177a21–b1). In doing so, he draws a clear line between contemplation and ordinary activities, leading us to recognize that a contemplative life is impractical for the majority (EN X 7, 1177b16–1178a2). Consequently, designating leisure as contemplative suggests a sense of exclusivity, thereby rendering leisure largely inaccessible to common people.

However, this contradicts Aristotle’s claim about the universal accessibility of leisure within the city-state. In Pol. VII 2, 1325b30–33, he presents a ‘whole-part rule’: “It is therefore clear that the best life for each individual person and for people as a whole in the city-state must necessarily be the same.” He emphasizes that the best life remains consistent whether considered at an individual level or for the collective society. Given that the best life (i.e. happiness) for ‘each individual person [ἑκάστῳ τε τῶν ἀνθρώπων]’ is essentially associated with the contemplative leisure, it logically follows that the best life for ‘people as a whole in the city-state [κοινῇ ταῖς πόλεσι καὶ τοῖς ἀνθρώποις]’ should also reflect this pursuit. In short, Aristotle emphasizes that leisure applies not only to philosophers but also to common people in the ideal city-state (Pol. II 9, 1269a34–36; cf. Pol. VII 15, 1334a11–14). His argument seems to be as follows: (a) the best life is the same for individuals and the collective society; (b) the best life for individuals is characterized by a leisurely lifestyle; (c) therefore, common people within the city-state can also partake in such a leisurely lifestyle to achieve this ideal. Although, in general, not all people in the city-state may share the same leisurely state, at least on a normative level, Aristotle insists that “to be a well-ordered city-state [καλῶς πολιτεύεσθαι]” demands facilitation of such a lifestyle for all of its members (Pol. II 9, 1269a34–35).

Based on the above discussion, a remarkable lack of coherence emerges across Aristotle’s portrayal of leisure. On the one hand, he characterizes leisure as a contemplative pursuit exclusive to philosophers, yet simultaneously emphasizes its accessibility to common people. This incoherence, named as ‘problem of universal accessibility in leisure’, has prompted various critiques of Aristotle’s moral philosophy. These critiques can be summarized as follows.

First, Aristotle’s ethical and political theories appeal to the universal human nature, which is thought to be intended to provide substantive advice and justification for daily ethical demands.6 However, if leisure is portrayed as an exclusive pursuit for philosophers, it may fail to accurately capture how people in general lead morally virtuous lives. Thus, leisure appears more as an idealized situation that none of us can experience, rather than a factual feature of human existence.7 Second, individuals with the privilege of leisure, particularly contemplators, tend to detach themselves from mundane concerns. As a result, they must rely on others to provide them with ‘external goods’. This reliance indicates that the possession of leisure depends on the contributions of others. Therefore, Aristotle cannot be seen as a fair and democratic gentleman who offers common people a place in the realm of leisure. Because of this, his conception of leisure inevitably invites various criticisms for his ideological ‘crime’.8 Third, it is crucial to recognize that contemplative leisure, when detached from broader practical concerns, does not inherently guarantee that individuals in this state are morally good. To illustrate this point, scholars often consider an extreme scenario: Suppose someone forcibly seize others’ private property to liberate themselves from basic needs and devote themselves to contemplation. One might argue that this fits Aristotle’s description of a leisurely lifestyle; thus, this person is ethically commendable. However, obtaining praiseworthy leisure through such amoral actions is, of course, contrary to our moral intuitions.9

Some interpreters have already noticed the challenge related to the universal accessibility of leisure in Aristotle’s philosophy. They have proposed two solutions to address this issue. First, they posit that Aristotle actually presupposes two distinct concepts of leisure: one refers to the contemplative state, while the other is associated with everyday practical activities. Second, they attempt to broaden the conceptual boundaries of contemplation, equating it with ordinary intellectual activities. By doing so, it leaves room for common people to have leisure, even though acknowledging that leisure contains elements of contemplation. In the following paragraphs, I will introduce these two proposed solutions and clarify their respective limitations.

According to the first solution, Aristotle’s writings contain two distinct notions of leisure with irreconcilable meanings. D. McLean (2017, 6), for instance, underscores the duality of leisure as both ‘telic’ and ‘instrumental’. Similarly, F. Solmsen (1964, 196) distinguishes between ‘leisure form private obligations’ and ‘leisure from political obligations’. Another scholar, R. C. Bartlett (1994, 393), also differentiates between leisure as ‘the end of human life’ and ‘the end of the lives of the citizens’.10 This division of leisure into two categories provides a possible solution to the problem mentioned before. Proponents of this solution argue that leisure is, in fact, accessible to everyone, but it takes on varying forms for different individuals. For philosophers, leisure manifests as a contemplative pursuit, involving intellectual and reflective endeavors. By contrast, for common people, leisure has a more communal, political, and instrumental feature, directly linked to the demands and circumstances of the daily existence.

However, the first proposed solution is unsatisfactory due to its dualistic presupposition. Essentially, it posits a parallel and even a contrasting structure in Aristotle’s psychological theories of moral behavior. This dualistic structure is based on the crucial division of the soul into rational and irrational components. The rational part can comprehend the causes of things through induction and deduction. By contrast, the irrational part serves as the seat of emotions – fear, hate, anger – or, in general terms, of desires. According to Aristotle, intellectual virtues are associated with the rational soul, while ethical virtues are linked to the irrational one (EN I 13, 1103a3–7, V 1, 1138b35–1139a5). This division further manifests in the contrast between two understandings of happiness, namely, the intellectual and inclusive lifestyles. The intellectual view holds that true happiness is exclusively tied to a contemplative, philosophical life, while the inclusive view argues that activities in accordance with ethical virtues (courage, temperance, etc.) are also integral to happiness. If the first solution is based on such a dualistic framework, it is inevitably trapped into the endless debates between these two standpoints.11 This makes it challenging to arrive at a coherent understanding of how people should live. This is because, essentially, the pair of notions ‘leisure belonging to common people – contemplative leisure’ is merely a terminological variant for ‘inclusive lifestyle – intellectual lifestyle’.

Proponents of the second solution focus on Aristotle’s notion of homonoia. Etymologically, this term consists of two components: the word ‘nous’, meaning mind or intellect, and the prefix ‘homo-’, which signifies ‘common’ or ‘shared’.12 Thus, homonoia literally implies the idea of collective or communal sharing of nous.13 Importantly, Aristotle closely associates nous with contemplation, which is defined as ‘the actualization of nous [ἡ...τοῦ νοῦ ἐνέργεια]’ (EN X 7, 1177b19). Accordingly, based on the semantic content of homonoia, it becomes possible for common people to engage in the actualization of nous, namely, contemplation. Therefore, even under a contemplative interpretation of leisure, there is still a room for common people to have leisure, as contemplation can be perceived as an accessible form of intellectual pursuit. In short, the second solution can be summarized as follows: (a) leisure is essentially associated with contemplation; (b) contemplation is defined as the actualization of nous; (c) nous can be expanded or generalized through the semantic content of homonoia; (d) therefore, leisure can be extended to a more inclusive dimension, making it available to common people.

The basic idea of this solution lies in advocating for an expanded interpretation of contemplation within Aristotle’s philosophy, moving beyond its narrow technical definition. For instance, K. Kalimtzis (2017, 54), in his culture-historical accounts of leisure, argues for a broad view of contemplative activity, encompassing a diverse range of intellectual experiences. This includes activities like strategic thinking during chess games and literary exploration through reading. S. Broadie (1991, 424) further refines this perspective. She suggests that contemplation should extend beyond the pursuit of ultimate causes and principles alone. Instead, contemplative activity can also manifest in ordinary or even random thoughts in everyday contexts. By recognizing these ordinary forms of contemplation, proponents of this solution defend an inclusive understanding of contemplative leisure accessible to the general population.

The second proposed solution also faces criticisms, with one key point that should be highlighted. That is, if contemplation is broadened to the ordinary intellectual activity, it inevitably contradicts its fundamental characteristic of being practiced for its own sake. For example, in productive activity (poiesis), artisans employ intellectual processes in order to create artifacts (EN V 5, 1140b2–3). Similarly, in practical activity (praxis), agents engage in deliberations in order to gain something, apart from the activity itself (EN X 7, 1177b3). ‘Leisure activities’ like reading books or playing chess are also being practiced for external purposes, such as pleasure or friendship. Ordinary intellectual activities, in these cases, seem at most instrumentally useful to a certain purpose which lies outside them, whereas the purpose of contemplation is contained in the activity itself. This principled distinction underscores that ordinary intellectual engagement cannot rightfully be categorized as contemplation within the Aristotelian framework. Consequently, participating in such activities might not grant common people the access to true contemplative leisure, as they fail to align with the core essence of contemplation.

Based on the preceding analysis, we have presented a thorny problem in Aristotle’s conception of leisure, that is, the issue of its universal accessibility. On the one hand, leisure appears exclusive to those engaged in contemplation. However, Aristotle’s ethical and political theories stress that leisure should be a customary and attainable way of life, accessible even to common people. To address this problem, two solutions have been critically introduced. The first solution adopts a dualistic perspective, which is philosophically unpromising because it cannot provide a consistent view of human flourishment. The second solution, focusing on homonoia, attempts to provide a more inclusive role for contemplation. However, this perspective may not fully align with the core essence of contemplation, thereby limiting its explanatory power. Now, to truly fix the problem, a fresh investigation into the semantic field surrounding Aristotle’s conception of leisure becomes necessary.

In Pol. VIII 3, 1337b29–32, Aristotle underscores leisure as a desirable state that individuals seek ‘in nature [φύσιv]’. This suggests that leisure not only encompasses ethical and political dimensions, but also carries a natural connotation. The natural aspects of leisure become evident when considering its connection with the intrinsic order of the soul. For Aristotle, the division between leisure and busyness is rooted in the heterogeneous nature of human soul, with different parts corresponding to different states (Pol. VII 14, 1333a16–30). Aristotle’s assertion in Magna Moralia (MM) provides additional insights into leisure’s natural character. He describes leisure as a state where human soul is well-ordered, meaning that passions are restrained by prudence and wisdom (MM I 34, 1198b12–20). The close connection between leisure and the psychic nature allows for defining leisure from a moral-psychological perspective. This now leads to a more fundamental question: Which specific state of human soul does leisure refer to?

Some scholars are perceptive to pay attention to the significance of linguistic analysis for conceptual study, by pointing to the etymological link between the word ‘leisure’ (schole) and the term ‘hexis’ (verb. echein, to have). Specifically speaking, K. Kalimtzis (2017, 55) claims that “schole, however, is not preparation, but something possessed; as previously noted, the word itself is possibly derived from the verb ‘to have’”. Similarly, J. Owens (1981, 715) highlights that leisure, or “its Greek counterpart schole is traced by etymologists to the same root as that of the Greek verb for ‘to have’.”14 These etymological links might indicate semantic connections between these words, providing an initial motivation to treat leisure and hexis as parallel concepts.15

Notably, Aristotle’s discussions of hexis are not confined to his ethical and political contexts, but also occupy a non-ignorable portion of his inquiries on nature.16 According to his philosophical lexicon, the term ‘hexis’ denotes a stable state wherein individuals have certain faculties (Metaph. Δ 20, 1022b8–12). Specifically, in his theory of soul, hexis represents the intermediate state between the soul’s initial and its full actualization:

Actualization is said in two ways, either as scientific knowledge is or as contemplating is. And it is evident actualization is as scientific knowledge is. For both sleep and waking depend on the presence of the soul; waking is analogous to contemplating, and sleep to having [ἔχειν] but not actualizing [μὴ ἐνεργεῖν] scientific knowledge. (DA B 1, 412a22–26)

Let us consider a case of perceptual activity introduced in De Anima (DA) B 5. Here, the perceiver resides in the hexis-state, possessing perceptual faculties without actually using them. Only when these faculties are actively engaged, does the perceiver’s soul progress from the hexis-state to a higher level of actualization (DA B 5, 417b16–19). The concept of ‘hexis’, in this context, specifically denotes the intermediate state within the soul’s two-stage process of actualization, where faculties are present but not fully realized. In short, hexis refers to a condition where human faculties are retained, serving as the precondition for individuals to engage in concrete activities.

For Aristotle, Leisure is also closely linked to human faculties. He argues that legislators should educate citizens to “be capable of engaging in leisure [δύvασθαι σχολάζειν]” (Pol. VII 14, 1334a9–10). Furthermore, Aristotle asserts that the most meritorious individuals within the city-state should “have the faculty to be at leisure [δύνωνται σχολάζειν]” (Pol. II 11, 1273a34). He even directly characterizes leisure as a function, emphasizing that the formation of a virtuous life entails “realizing the function of leisure [ἐν τῇ σχολῇ τὸ ἔργον]” (Pol. VII 15, 1334a17). From these cases, it becomes evident that Aristotle employs the notion of leisure in alignment with the semantic content of hexis-vocabulary, as both connote a state where individuals possess faculties.

In addition, the parallel between leisure and hexis is also evident within the ethical and political realms. Aristotle describes the soul’s engagement in the state of initial actualization as a precondition for entering the moral community. This state, termed as the hexis-state, signifies that individuals possess certain faculties which they have not yet fully actualized through practical activities. Notably, for individuals to constitute a virtuous life, it becomes imperative for their souls to achieve second-level actualization. At this level, they have developed their faculties into practical use:

We acquire virtues by undertaking the first-level actualization [τὰς δ’ ἀρετὰς λαμβάνομεν ἐνεργήσαντες πρότερον], as also happens in the case of the craft knowledges as well. For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them, e.g., men become builders by building and lyre-players by playing the lyre; so too we become just by practicing [πράττοντες] just activities, temperate by practicing temperate activities, brave by practicing brave activities. (EN II 1, 1103a31–1103b2)

In Aristotle’s ethical framework, the journey towards acquiring virtues starts with the soul’s ‘initial actualization [ἐνεργήσαντες πρότερον]’, which corresponds to the allegedly hexis-state (EN II 1, 1103a31). In this state, individuals have various faculties that provide the potential for leading a virtuous life.17 According to Aristotle, this potential can only be realized by ‘practicing [πράττοντες]’ (EN II 1, 1103b1). This occurs as individuals actually engage in concrete activities, thus facilitating their transition from the hexis-state to the state of gaining virtuous character traits such as justice, temperance, and bravery.

However, Aristotle highlights that merely having the potential or faculties, as found in the hexis-state, is insufficient for leading a virtuous life. He argues that, in order to acquire virtues, individuals must take actions in an appropriate manner – ‘practicing well [εὖ πράξει]’ as he states (EN I 8, 1099a3). But, to be specific, what does ‘practicing well’ signify? Aristotle explains that it requires individuals in the hexis-state to undertake the soul’s second-level actualization in the direction of virtuous completion. In EN II 5, 1106a11–13, he delves into an exploration of what the virtue is. He rejects the idea of virtue as merely a kind of passion or faculty, by ultimately concluding that the virtue must be a specific type of hexis. It should be noted that Aristotle does not directly equate virtue with hexis here. Instead, he posits virtue as a subset species within the broader genus of hexis. This implies that there exist certain differentia that set virtue apart within the conceptual realm of hexis. Notably, Aristotle’s statement in Phy. VII 3, 246a11–12, “some hexeis are virtues and others are vices [αἱ μὲν γὰρ ἀρεταὶ αἱ δὲ κακίαι τῶν ἕξεων]”, which suggests that, under the category of hexis, there exist both virtue and vice. The distinction between the two lies in the fact that the virtue, in contrast to the vice, represents a form of completion:

Virtue is a sort of completion [ἡ μὲν ἀρετὴ τελείωσίς τις], for when each thing acquires its own virtue, at that point it is said to be complete [τέλειον], since then it is most of all in accord with its nature. (Phys. VII 3, 246a13–15; cf. Phys. VII 3, 246a20–b3)

According to Aristotle, hexis refers to an intermediate state in human development towards completion. The hexis-state, in this process, signifies the potential for the formation of virtue, as it provides the fundamental faculties needed. However, hexis can also undergo a troubling transformation, leading to vice instead of virtue. This indicates the malleable nature of hexis, capable of acquiring either virtue or vice. It depends on whether the relevant faculties are actualized in a positive or negative direction.

When reexamining Aristotle’s discussion of leisure, we can find that he also views it as a potentially malleable state which can lead to either virtue or vice. In Pol. VII 15, 1334a14, Aristotle advises citizens to cultivate ‘the virtues of leisure [τὴν σχολὴν ἀρετὰς]’. It is important to note that he does not intend to define leisure as a virtue by itself. Instead, analogous to his approach in EN II 5, he argues that leisure can be perceived as a broader genus within which the virtue is a subset. To distinguish virtue from the conceptual scope of leisure, a distinct factor is required. Correspondingly, leisure is presented as the antecedent state necessary for acquiring virtue: “leisure is required for the formation of virtue [δεῖ γὰρ σχολῆς καὶ πρὸς τὴν γένεσιν τῆς ἀρετῆς]” (Pol. VII 9, 1329a1; cf. Pol. II 5, 1278a20–21). However, while leisure provides the opportunity to develop a virtuous life, it does not guarantee the actual formation of virtue.

Aristotle even explicitly discusses cases where leisure leads to vice rather than virtue, thereby highlighting its potential for negative outcomes. For instance, he faults the Lacedemonians for exhibiting excellence in war but behaving no better than slaves during leisure (Pol. VII 15, 1334a38–41). He also notes that Spartan women, despite enjoying much leisure due to their exemption from military service, failed to cultivate virtue and instead overindulged in pleasures and luxury (Pol. II 9, 1269b20–1270a15). This suggests that, like hexis, leisure is ethically neutral and can lead to either a virtuous life or a vicious one. The key question then becomes: What influences the outcome of leisure? Perhaps, for Aristotle, the answer is that virtue can be cultivated from leisure only if individuals in this state focus on the pursuit of ‘the good [ἀγαθῶν]’ (Pol. VII 15, 1334a34). By contrast, the Lacedemonians and Spartan women, though possessing leisure, erred in prioritizing warfare and pleasure over the good, thereby failing to attain the virtuous completion.

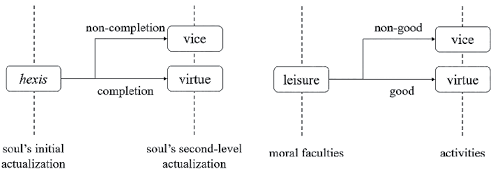

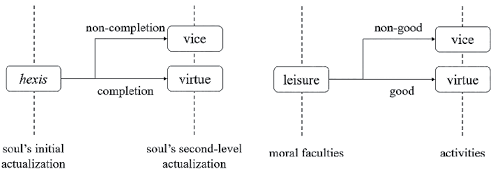

As it is evident from the preceding analysis, there is a parallel between leisure and hexis in Aristotle’s moral psychology. Hexis refers to the state where the soul has undertaken the initial actualization. In this state, moral agents possess the relevant faculties required for entering the moral community. Further actualization of these faculties towards completion leads to virtuous conducts. Correspondingly, leisure is characterized as the state of possessing the moral faculties. This state implies the potential for engaging in intellectual and practical activities. When these activities are directed towards the good, leisure cultivates virtuous practices. The parallel relationship between them can be visualized in the following diagram:

According to Aristotle, hexis is identified as a fundamental state of human existence. In the psychological realm, it signifies the condition of possessing faculties, where the soul resides in the stage of the initial actualization. Within the moral domain, it indicates a state in which individuals have the relevant faculties required for ethical conducts. Since hexis denotes a very basic human condition in both natural and practical domains, and considering the parallel relationship between leisure and hexis, it plausibly follows that leisure is not just confined to a contemplative lifestyle. Instead, leisure constitutes our basic humanity and can be possessed by common people.

In this paper, I have endeavored to redefine leisure as a moral-psychological concept corresponding to the hexis-state of the soul. To elaborate on this, I first traced the term ‘leisure’ back to its etymological origin, ‘hexis’, presenting their philological connection. I then examined the similarities between their semantic contents in Aristotle’s philosophy, concluding that both denote a potentially malleable state in which faculties are kept. This explanation leads to a revised sense of leisure: rather than solely denoting a contemplative state, leisure is posited as a basic condition of individuals.

By understanding leisure in this way, the problem of its universal accessibility is resolved. Leisure is no longer viewed as an exclusive state reserved solely for philosophers, but, instead, it is recognized as a universal condition inherent in human nature. According to Aristotle, individuals possess faculties enabling them to act morally and achieve virtuous completion. He identifies this state where these faculties are maintained as a condition akin to leisure. From this perspective, leisure is accessible to common people in their everyday lives.

Bartlett, R. C., 1994. The “Realism” of Classical Political Science. American Political Science Review 38(2): 381–402. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111409

Beekes, R., 2010. Etymological Dictionary of Greek (2 vols.). Leiden & Boston: Brill.

Bowler, M., 2014. Heidegger, Aristotle, and Philosophical Leisure. Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association 88: 273–283. http://doi.org/10.5840/acpaproc201612037

Broadie, S., 1991. Ethics with Aristotle. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cooper, J. M., 2004. Knowledge, Nature and the Good: Essays on Ancient Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Glotz, G., 1996. Ancient Greece at Work: An Economic History from the Homeric Period to the Roman Conquest, translated by Dobie, M. R., London: Routledge.

Hardie, W. F. R., 1965. The Final Good in Aristotle’s Ethics. Philosophy 40(154): 277–295. http://doi.org/10.1017/s0031819100069709

Holba, A., 2007. Philosophical Leisure: Recuperative Practice for Human Communication. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press.

Kalimtzis, K., 2017. An Inquiry into the Philosophical Concept of Schole: Leisure as a Political End. New York: Bloomsbury.

Kenny,>A., 1992. Aristotle on the Perfect Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lear, J., 1988. Aristotle: The Desire to Understand. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (Eds.), 1996. A Greek-English Lexicon: With a Revise Supplement. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McLean, D., 2017. Speaking of Virtue Ethics: What Has Happened to Leisure? Annals of Leisure Research 20(5): 529–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2017.1357046

Nightingale, A. W., 2004. Spectacles of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy: Theoria in its Cultural Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nussbaum, M., 1990. Aristotle on Human Nature and the Foundations of Ethics. In: Altham, J. E. J. & Harrison, R. (Eds.), World, Mind and Ethics, 86–131. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Owens, J., 1981. Aristotle on Leisure. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 11(4): 713–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/00455091.1981.10716332

Ramsay, H., 2005. Reclaiming Leisure: Art, Sport and Philosophy. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rodrigo, P., 2011. The Dynamic of Hexis in Aristotle’s Philosophy. Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology 42(1): 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071773.2011.11006728

Snyder, J. T., 2018. Leisure in Aristotle’s Political Thought. Polis: The Journal for Ancient Greek Political Thought 35: 356–373. https://doi.org/10.1163/20512996-12340172

Solmsen, F., 1964. Leisure and Play in Aristotle’s Ideal States. Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 107(3): 193–220. https://doi.org/10.2307/41244222

Yannig, L., 2015. Aristotle on Choosing Virtuous Action for its Own Sake. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 96(3): 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/papq.12078

1 Translations of Aristotle’s works are my own except as noted.

2 Cf. Physics (Phys.) II 9, 200a6–10; Parts of Animals (PA) I 1, 642b4–13; see also Cooper (2004, 130–131).

3 Cf. Snyder (2018).

4 While Aristotle literally states in EN I 7, 1097a29 that ordinary virtuous activity is also practiced for its own sake, he qualifies this as only applying to a secondary degree. In contrast, when strictly considering the criterion of ‘being practiced for its own sake’, contemplation is the only true candidate (cf. EN X 7, 1178a9). For a detailed discussion, see Yannig (2015).

5 For the strong correlation between leisure and contemplation, see Kalimtzis (2017, 58–62), Holba (2007, 60), Ramsay (2005, 12), and Bowler (2014).

6 Aristotle highlights that moral agents should engage in communal rather than solitary practices (EN I 7, 1097b7–11). He argues that individuals with an inherently solitary disposition are either superior or inferior to humanity, but not of it (Pol. I 2, 1253a1–7). This implies that his ethical and political theories are primarily concerned with common individuals. For a defense of this position, see Nussbaum (1995).

7 Cf. Broadie (1991, 420–424).

8 Cf. Glotz (1996, 161–163, 322–324).

9 Cf. Nightingale (2004, 222), Kenny (1992, 89–90), Broadie (1991, 420), and Lear (1988, 314–316).

10 For other examples supporting the first solution, see Ramsay (2005, 47) and Holba (2007, 64).

11 This debate can be traced back to Hardie (1965).

12 In Aristotelian framework, nous represents the essential intellectual capacity that enables rational thought. Notably, it seems to operate on a higher plane and is not easily accessible to the common people. In theoretical reasoning, nous can grasp primary principles directly without the need for step-by-step logical processes (cf. EN Ζ 7, 1141a20). In the ethical realm, Aristotle refers to a so-called ‘practical nous [τοῦ πρακτικοῦ νοῦ]’, which functions as a kind of moral intuition, helping agents make the right decisions in situations where logos may be insufficient (cf. DA Γ 10, 433a16). This suggests that nous is a special, almost divine, intellectual faculty that allows humans to perceive fundamental truths.

13 Like many Greek philosophical terms, homonoia admits of many translations, with recent scholarly choices including ‘unanimity’, ‘concord’, ‘like-mindedness’, and even ‘political friendship’. However, these translations often obscure its literal meaning of ‘common sharing of nous’, which is crucial for addressing the problem mentioned here. For this reason, it is preferable to retain the original Greek term in the discussion; cf. Liddell & Scott (1996, 1226).

14 For a comprehensive discussion of their etymological relationship, see Beekes (2010, 1439).

15 Aristotle reinterprets the traditional meaning of hexis, by transforming it into a technical term within his philosophical vocabulary. It is commonly understood as a type of ‘state’, ‘quality’, ‘active condition’, ‘habit’, ‘disposition’, or ‘way of being’. While each of these understandings highlights different aspects of hexis, none of them fully captures its most fundamental sense. The key point is that hexis refers to the possession of certain human faculties which play a causal role in both biological and ethical actions for Aristotle.

16 Rodrigo (2011, 7) helpfully reminds us that hexis ‘has a very wide scope’.

17 Aristotle asserts that performing virtuous activities requires certain agent-conditions, which include individuals residing in a stable hexis-state, see EN II 4, 1109a29–34.