Politologija ISSN 1392-1681 eISSN 2424-6034

2023/3, vol. 111, pp. 8–40 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Polit.2023.111.1

Attitudes of Parliamentary Candidates towards the Politics of Memory in Post-Communist Lithuania1

Irmina Matonytė

Professor, General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania,

Research Group of Global Politics

E-mail: irmina.matonyte@lka.lt

Gintaras Šumskas

Associate professor, Vytautas Magnus University, Department of Political Science

E-mail: gintaras.sumskas@vdu.lt

Abstract: The paper dwells on the longitudinal data set of Lithuanian parliamentary candidates’ views and investigates the post-communist politics of memory. The analyzed surveys are conducted in 2008, 2012 and 2016. Several hypotheses regarding the impact of time, democratic consolidation and geopolitical challenges on the national level of the politics of memory are tested, and we examine differences among party families regarding the politics of memory. The list of dependent variables of this study includes the attitudes of the parliamentary candidates and their determination to implement lustration, ban the public display of Soviet symbols and implement the claim that Russia must compensate the damage inflicted on Lithuania during the Soviet occupation. The study reveals that the politics of memory remains a matter of contention shaped by the dynamic interaction of three kinds of logic: transitional (based on the need to mark a break from the previous regime), post-transitional (encouraged by expiring early transitional conventions and re-articulated geopolitical visions), and partisan (inspired by multi-party electoral competition).

Key words: politics of memory, parliamentary candidates, Soviet symbols, compensation from Russia, collaboration, Lithuania.

Kandidatų į Seimą požiūriai į atminties politiką pokomunistinėje Lietuvoje

Santrauka. Straipsnyje aptariamas ir analizuojamas kandidatų į Lietuvos Respublikos Seimo narius požiūrių į atminties politiką duomenų rinkinys. Analizuojamos ãpklausos, atliktos 2008, 2012 ir 2016 metais. Tikrinamos kelios hipotezės dėl laiko, demokratinės konsolidacijos ir geopolitinių iššūkių įtakos atminties politikai, nagrinėjami partijų šeimų skirtumai atminties politikos atžvilgiu. Šios studijos priklausomų kintamųjų sąrašas apima kandidatų į parlamentarus nuostatas ir jų pasiryžimą įgyvendinti liustraciją, uždrausti viešą sovietinės simbolikos demonstravimą ir įgyvendinti reikalavimą, kad Rusija atlygintų žalą, Lietuvai sukeltą per sovietų okupacijos metus. Tyrimas atskleidžia, kad atminties politika yra intensyvių politinių ginčų objektas, kurį formuoja dinamiška trijų logikų sąveika: pereinamojo laikotarpio (poreikio išreikšti atotrūkį nuo sovietinio režimo), posttranzitinio (kurį skatina nustojantys galioti ankstyvojo pereinamojo laikotarpio susitarimai ir naujai peržiūrimos geopolitinės vizijos) ir partinio (įkvėpto daugiapartinės rinkimų konkurencijos).

Reikšminiai žodžiai: atminties politika, kandidatai į Seimą, sovietiniai simboliai, kompensacija iš Rusijos, kolaboravimas, Lietuva.

_________

Received: 05/04/2023. Accepted: 03/07/2023

Copyright © 2023 Irmina Matonytė, Gintaras Šumskas. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

________

Introduction: The post-communist politics of memory and the parliamentary candidates

In post-communist times, the national, transnational, and international politics of memory remain hotly contested. Historians, political philosophers, sociologists, comparative political scientists, cultural anthropologists, and lawyers produce copious amounts of academic research on these and related issues. However, the analysis focuses mostly on the tip of the iceberg, i.e. on the tightly intertwined legal, institutional, commemorative, and monumental dimensions. There are case studies that analyze the content and the dynamics of decisions of political elites – elites that promote, and eventually revise those decisions as well as initiatives in reaction to the structural and contingent characteristics of transition and post-transition2 and competitive electoral processes.3 These studies mostly deal with discrete issues and temporalities of memory. They seldom question whether politicians treat the politics of memory as an aggregate policy sphere (thus putting forward and manipulating many measures at once). One notable exception is Pettai & Pettai, where a complex matrix assessing various measures of post-communist transitional justice is used.4 David explores several combinations of the instruments of the politics of memory in another politico-cultural context (Japan–Korea).5

These studies primarily focus on the period of rupture, leading to the regime change, and employ a ‘linear and continuous’ time approach as if the reasons behind an active interest into the past eventually expire when the transition is over and democracy is consolidated. Although social attitudes towards the recent past are acknowledged as constituting one of the dimensions which structure the political field, memory researchers rarely focus on electoral campaigns or other specific instances of ‘high season’ for political communication. However, the discourse of the politics of memory may be understood ‘not as a carrier of meaning but as an activity in and of itself.’6

Politics of memory provided strong arguments for Europeanization of the newly independent Baltic States7 and it still endows Baltic politicians with unique instruments of mobilization.8 Particularly notorious instances of political instrumentalism of the communist past were the removal of the Soviet Bronze Soldier in Tallinn in 2007 and the demolition of the Soviet Statutes on the Green Bridge in Vilnius in 2015. The 2014 Russia’s annexation of Crimea contributed to another upsurge of the politics of memory in post-communist Europe in general, and in the Baltic countries in particular.9

The analysis of parliamentary candidates’ attitudes in this case study constitutes one of its major contributions, as this type of empirics is under-researched in post-communist memory politics. We specifically focus on parliamentary candidates since they are the key figures in the representational process of parliamentary democracies. In addition, they are usually also mnemonic agents. For instance, Bernhard and Kubik,10 developed the typology of mnemonic actors where they distinguish mnemonic warriors, pluralists, and abnegators.

In politics, collective memory exerts its influence both from the bottom up, as folk interpretations of the past affect understandings of political elites, as well as from the top down, as statements by public figures emphasize certain events while silencing or forgetting others.11 As observed by numerous researchers, the politics of memory encompasses a wide range of mnemonic actors, concerns various issues, employs different instruments, where legal, institutional, commemorative, symbolic and monumental dimensions are tightly intertwined. The politics of memory refers to a wide range of socio-political mechanisms and processes, which shape public perceptions of the past and help to articulate as well as display past-related collective values.

Along with political elites, the mnemonic actors include representatives of other institutions and communities. The repertoire of the parliamentary politics of memory includes political statements, legislative acts and budgetary allocations that substantiate particular interpretations of the past.12 In this article, we use the term politics of memory, pointing to dynamic, interactive, and purposeful activities in the field of memory and to the involved political actors, who in the parliamentary campaigns contest existing policies relative to collective memory of the Soviet past.

Parliamentary candidates’ attitudes towards specific, memory-related legislation, which are passed by a national parliament and solicit public controversies, constitute a worthy reservoir of empirical data. They allow examining if (how) the politics of memory – which captures formal decisions made by incumbent politicians (alias by the democratic majority, or by the coalition government) – is reactivated in electoral campaigns, which specifically frame ‘situated practices in public discourse.’13 The surveys of candidates’ stances invite us to examine sets of attitudes and arguments, which address various aspects of collective memory of the Soviet past as a powerful, action-oriented resource that shapes understanding of public controversies over individual and collective meaning of the recent communist regime. The politics of memory during electoral campaigns might become a centrifugal force questioning the enacted policies of truth and justice which strive to institutionalize, make certain patterns of reckoning with the past irreversible and, by default, it attempts to suppress the virulent political in memory and to reduce the range of mnemonic struggles as well as viable actors. Candidates’ attitudes as an empirical basis of research are especially worthy in post-communist settings because typically post-communist party programs (electoral manifestos) are shallow with very little explicit information relative to the politics of memory. In addition, an analysis of the multidimensionality of the Lithuanian political space revealed that the party candidates and the electorate share only one single policy dimension – the post-Soviet versus anti-Soviet cleavage combined with the attitudes towards Russia.14

Lithuania is classified as a post-communist country with a ‘strong approach to transitional justice.’15 Since the early post-communist times, in Lithuania lustration is treated broadly and is related to the overall rejection of the culture of nomenklatura, a politico-administrative system, based on the communist party-loyalty, lack of concerns in public interests as well as the arbitrary and corrupt decision-making process. The elements of the anti-nomenklatura and anti-KGB discourse have always been and are still virulent in Lithuanian electoral campaigns.16 The elements of discourse, directed against the Soviet nomenklatura, have noticeably extended also to the most recent parliamentary campaign, which took place in October 2020. The 1998 Lithuania’s lustration law (adopted in 1998) banned former Soviet secret services collaborators from high-ranking positions in public service and the educational system. Amendments to Lithuania’s electoral law require candidates to inform voters about any past collaboration with the KGB. Legislation concerning compensation for damage resulting from the Soviet occupation was adopted in June 2000.17 Since 2008, the Lithuanian civil code bans the public display of Soviet (and Nazi) symbols and prohibits their sale, except as antiques. All three laws have been amended several times. The public display of Soviet symbols (and the legal regulation of the matter) relentlessly stirs political emotions in Lithuania, where the role of cultural and intellectual elites remains very prominent.18 Specific clauses on decommunization have also been included into the post-electoral coalition agreement in 2020.

However, there are no clearly-cut and sharp lines distinguishing how political parties and political entrepreneurs use the politics of memory.19 The Lithuanian party system is evolving from a two-party system towards a multiparty system.20 The origins of two mainstream parties – the Social Democrats and the Conservatives – can be traced back to the very early post-communist transition. The consolidation of the liberal camp and the emergence of populist contenders happened only around the time of Lithuania’s integration into the EU and NATO (2004). The Liberals entered the coalition government in 2008–2012 and reached the peak of their popularity before the parliamentary elections of 2016, but a corruption scandal decreased their popularity.21 In 2016, populists significantly expanded their electoral base taking advantage of the reputation crisis in the liberal camp.

Based on this context, we examine Lithuanian parliamentary candidates’ stances towards the politics of memory, expressed in the 2008, 2012 and 2016 parliamentary campaigns. These attitudes are offered on the electoral marketplace, where they attract various levels of electoral support. Parliamentary candidates, because of their public visibility, resources and greater authority lead, or at least efficiently affect, public opinion on any issue – the politics of memory included. Indeed, the parliamentary candidates are the ‘political elites in the making,’ who – if successful in elections – will hold strategic positions in policymaking.

1. Theoretical framework: transitional, post-transitional, and partisan logic of the politics of memory

The seminal writings of Elster have forcefully established that to be effective, measures of transitional justice must be quick and strong, due to that later on the momentum is quickly lost;22 emotions and memories associated with the previous repressive regime might eventually dissipate, replaced by other socio-economic and political concerns. The Lithuanian statehood was re-established in 1990–1991 and Lithuania’s relations with Russia, the successor state of its former occupant, are tense – more tense and difficult than those of other post-communist Central Eastern European democracies that did not have to fight for international recognition of their newly asserted sovereignty after the breakdown of communism. The sovereignty of a newly re-established State is closely related to the very nationhood, which, after complicated past experiences, embarks on searches for novel opportunities to emphasize its values, ideologies, aspirations, and ideals. Among these, the relationship to its former occupant’s successor is of special importance.

In the Baltic States, politics of memory was of utmost importance in the breakthrough years. In 1989–1990 the secret protocols of the Ribbentrop–Molotov pact were politically condemned. Post-communist Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia claimed legal continuity from their interwar statehoods. Particularly in Lithuania, harsh memory debates emerged as a powerful political axis.23

To mark the rupture, ‘occupants’ and ‘collaborators’ were banished from the national community of heroes, Soviet symbols were proclaimed rogue, and new initiatives aimed at post-colonial assertion of Lithuanian nationhood were put forward. Instruments used for that purpose include awaiting recognition from Russia that the Baltic States were indeed occupied by the USSR; that the Soviet regime had a negative impact on Lithuania; and that Russia, the legal successor of the USSR, should acknowledge its wrongdoings. Radical measures to this effect were adopted because the early transitional politics of memory thrive in that very peculiar emotional context where retributive emotions abound and the collective desire to punish those who incarnate the fallen regime is strong.24

The measures of transitional politics of memory interlink democratization with social attitudes and practices. The case of ‘lustration’ (the banning of communist officials and the secret police from occupying decision-making positions in new post-communist democracies) is revelatory, since it provides a ritual purification as well as represents a change in the moral culture of citizens.25 Similar value-changing effects are attributed to the ban on public display of Soviet symbols.

In the domain of international relations, current paradigms of human rights and reconciliation are characterized by the enabling of former victims to present their interpretations of the past and to question dominant narratives. To transcend the counterproductive blame games across the (new) borders between the former colony and its imperial center, memory and reconciliation need to be interwoven.26 Baltic demands for Russia to compensate the damages inflicted by the Soviet occupation merit special consideration. ‘Baltic truth and justice politics have reverberated in the three countries bilateral relations with Russia <…>. The flow of influence has not always been one way.’27 The temporality of transitional politics of memory is defined narrowly: it seeks to compensate victims and punish wrongdoers. It is crucial to inquire how sustainable the transitional, revolutionary logic of post-communist politics of memory is, and how much it still aims at marking the rupture from the previous regime and signaling a new beginning.

In late post-communist times, the memories of the Soviet Union have already reached their radioactive ‘half-life,’ becoming a cold memory. A past that has reached its half-life threshold (i.e. it is no longer a living or immediate memory for a critical mass of the population) is ‘susceptible to being approached from a normalizing angle, rather than with a loaded emotional agenda of seeking memorial justice.’28 Revisions in the politics of memory become even more important as many post-communist States experience politicized, delayed, narrowed or truncated measures over the course of their transitional justice efforts.29

Chronologically, the post-transitional politics of memory begins when democratic politics not only becomes ‘the only game in town,’ but when a society also invites itself to re-examine what in the transitional period was ‘present.’ The main idea of the post-transitional logic of the politics of memory is that democratic consolidation allows and encourages a tendency to defy the dominant view and to revisit the early initiatives of transitional politics of memory. It offers a qualitatively new and different way of looking at issues of memory. The post-transitional logic of the politics of memory is less radical: it explicitly relies on the rule of law principles and refers to the evaluation of the immediate transitional justice process. Thus, the post-transitional politics of memory arises as a function of transitional policies of memory, or, better to say, is generated by their failure.

The notion of post-transition implies that numerous issues might be re-examined in what would most likely be a calmer emotional context, inviting critical reconsideration of previous orders and decisions.30 The initial formats of post-communist transitions, based on explicit elite pacts and tacit elites’ conventions, which have been functional in maintaining social peace under a new regime, might have expired. Under the conditions of consolidated democracy, tolerance for partial and biased means of memory policies decreases and more attention is paid to the full establishment of the rule of law, to the respect for human rights, and to the values of an open society. In the post-transitional period, lustration may come to be seen as a violation of human rights (rights to work and to choose freely by what work to make a living) and as an extension of illegitimate retroactive justice. If it is post-transitional lustration, then settling accounts from the more distant past is even more damaging as it becomes a quasi-autonomous sphere of elite action, disconnected from public control.

As for foreign affairs, the accession to the EU and NATO in 2004 brought Lithuania into a new geopolitical situation, in which an imperative of distancing itself from the former colonial center (Russia) seemed as losing its urgency and as the setting where the politics of memory might be ‘unfastened.’ Alongside, post-communist EU enlargement has catalyzed normative debates about the communist past and raised questions about the EU’s moral engagement in advancing justice with respect to the prior suffering of former colonies of the USSR.31 Thus, the post-transitional politics of memory might lead not only to a revision of the principles of lustration, but also to shifts in foreign affairs. Multi-layered and close links between collective memory and various policies of memory may reinvigorate the bilateral or transnational debates and be the reason why so many countries fail in their efforts to pursue transitional or historical justice with their neighbors (as shown, for instance, in the analysis of a still unfinished reconciliation between Japan and Korea).32 Claims of compensation or an official apology from Russia is a measure of the politics of memory in Lithuania insofar as it unequivocally evokes the moral vocabulary of guilt, shame, responsibility and remembering, i.e. ethical notions which widely bypass transitional urgency to mark the rupture and essentially frame collective identity.33

Another typologically distinguishable logic of the politics of memory during the electoral campaigns relates to multi-party democratic competition. The democratic institutions of fair and free elections and the multi-party system empower, and oblige, political candidates to propose various ways of collective dealing with traumatic past, to contest diverse interpretations of historical events and to institutionalize frames of collective memory. Political entrepreneurs might be quick to react to collective memory related issues, especially if they remind the voters those parts of the past, which would delegitimize their political rivals. On the contrary, they might try to conceal other past episodes that negatively implicate them.

During an election campaign, candidates’ attitudes towards the politics of memory may be considered as part of the partisan competition for voter support. The potential for a post-communist partisan politics of memory is huge. The reasons for partisan elites to reactivate the past and politicize selected aspects of collective memory may include not only their search for historical truth, but also their attempts to divert the voters’ attention from financial and economic difficulties, mismanagement of reforms, and their severe social costs. Alternatively, incumbent elites might initiate laws towards the end of their parliamentary term that would harm their opposition or significantly reduce available alternatives for memory policies.34

However, in democracies, uses and abuses of the past by elites cannot be reduced to vulgar instrumentalism. Viable political actors care about the ideological coherence of those claims as well as about their ethical as well as cultural consequences.35 There may be segments of the population that want to see changes in the current politics of memory and political parties may want to respond to those expectations.

Therefore, the thesis of opportunist instrumentalism of the past, which refuses to accept that political actors are likely to hold firm positions on memory matters, needs to be revisited. A good way to test this thesis is by comparing parliamentary candidates’ announced stances on the issues of politics of memory and seeing how coherent those partisan stances are, whether they change from one electoral campaign to another, and in which direction the eventual changes unfold. This type of inquiry would also address research questions such as how ideological, stable, and coherent political parties’ stances are vis-à-vis the politics of memory and how (if) multi-party competition affects the politics of memory. Even though personalization of electoral campaigns is becoming the new fashion of political communication, political parties still serve as the main anchors in democratic elections. Post-communist Europe is known for the problems related to the development of stable partisan commitments among political elites.36 Empirical studies reveal that while party labels in post-communist countries are switched relatively often, major political vectors do not change as much as it may appear to external observers.37 These insights encourage us to use the notion of ‘party families,’ where a ‘party family’ functions as a perceptual screen and influences how the voters evaluate issues and candidates. Similar parties might be grouped into what is called ‘party families.’ The notion of party families is based on the criteria of shared ideology/policies, genetic origin, and membership in international party federations.38 Several parties could be aggregated under the same label instead of the extensive documentation of constantly changing brand names of the parties.

As for the impact of time and democratic consolidation on the dynamics of the politics of memory, we could typologically distinguish three temporalities that guide the politics of memory: the transitional, backward-looking temporality when coping with a traumatic past, the post-transitional projection of a liberal democratic future, and partisan ‘here-and-now’ oriented democratic competition.

2. The case study: hypotheses and research design

Following the above political context and the logic of transition, which, in Lithuania, resulted in dealing with the Soviet past harshly, we would expect that the political appetite for revenge would diminish with each electoral cycle, replaced by more moderate and restrained attitudes towards the Soviet past, its symbols, and collaborators, while negative feelings vis-à-vis the former imperial center (Russia) would be soothed. Accordingly, we would expect that, comparing data from 2008–2016:

H1. Parliamentary candidates’ attitudes towards the politics of memory will be dynamic, changing into lukewarm, permissive attitudes (de-radicalization).

The alternative, post-transitional logic suggests that with every year of democratic experience the fabric of political-cultural sensitivities significantly alters, eventually expanding and refining harsh judgments about the Soviet past. Accordingly, we would expect that, comparing 2008–2016 data:

H2. Parliamentary candidates’ attitudes towards the politics of memory will tend to radicalize around contested issues.

According to partisan logic, we would expect that during 2008–2016 Lithuanian politicians’ attitudes towards the politics of memory would cluster as specifically partisan. In particular:

H3. Representatives of different political party families will significantly diverge in their attitudes towards the politics of memory.

Alongside, we would expect that groupings by party families, given that they fit the above political context of Lithuania’s political system and are based on the criteria of shared ideologies and genetic origin, would provide distinguishable and concentrated party-family clusters of attitudes towards the politics of memory.

H4. The representatives of political party families will be coherent and consistent in their views.

The candidates’ attitudes towards the legislation, in particular those regulating lustration, the ban of public display of the Soviet symbols, and the demand of compensation from Russia, could serve as proxies for assessing the dominant logics of electorally contestable issues of the politics of memory. They allow the measurement of the content and the changes in attitudes about the politics of memory as expressed by parliamentary candidates in election campaigns in Lithuania in 2008, 2012 and 2016. Obviously, we should keep in mind that politicians may or may not treat the politics of memory as an aggregate policy sphere and that the selected proxies might reinforce or contradict each other, or be considered as discrete policy stances.

This factual situation enables us to study in situ the features of the politics of memory, its politization, and its political agency. The empirical data are obtained from a joint project of the Institute of International Relations and Political Science at Vilnius University, Transparency International Lithuania and the Central Electoral Commission of the Republic of Lithuania. The on-going project publishes political candidates’ responses on the website ‘Mano balsas’ (www.manobalsas.lt). The website in Lithuania has been in operation since 2007, and it makes the on-line questionnaires available to anyone who wants to check the proximity of their views to any political candidate.39 The questionnaires are designed by national experts for each election and reflect the most intensive public discussions. The questionnaires include 40–60 political issues that the respondent must evaluate using a scale of one to four (4 means ‘Strongly agree’, 3 - ‘Agree’, 2 – ‘Disagree’ and 1 means ‘Strongly disagree’). The list of the survey questions used in our study is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. List of the survey questions

|

Variables |

Description and Coding |

|

|

1. |

Collaboration with the KGB |

Question wording: Should restrictions be imposed on former KGB collaborators regarding holding positions in the civil service and education? The list of answer options: Strongly disagree, Disagree, Agree, and Strongly agree. |

|

2. |

Soviet symbols |

Question wording: Should Soviet symbols be prohibited? The list of answer options: Strongly disagree, Disagree, Agree and Strongly agree. |

|

3. |

Compensation from Russia |

Question wording: Should Lithuania claim compensation from Russia for the damage inflicted by the Soviet occupation? The list of answer options: Strongly disagree, Disagree, Agree and Strongly agree. |

Limitations. The surveys do not produce textual information, which would qualitatively substantiate interpretations. Only candidates to the national parliament answer the questions related to the politics of memory (the questionnaires filled by the candidates to the European Parliament did not include comparable items related to the politics of memory). The candidate survey, conducted during the parliamentary campaign, which took place in October 2020, does not contain comparable questions anymore. Alongside, a visible limitation of our sample is that, due to small N, the design of our study does not permit adequate analysis of the attitudes of Polish minority representatives.

All candidates to the Lithuanian Parliament, the Seimas, for the years 2008, 2012 and 2016 were invited to complete the questionnaire. Answers of around 300 respondents (15–23 percent of the total number of candidates) representing each of three electoral terms are analyzed. Noteworthy, candidates who had a good chance of winning were overrepresented in all three samples (our final data set in 2008 includes 70, one-half of the actually elected parliamentarians, in 2012 – 48, one-third of the actually elected parliamentarians and in 2016 – 64, again almost one-half of the actually elected parliamentarians).40 See Table 2 for a more detailed description of the sample.

Table 2. Overview of the sample

|

Election year |

Number of respondents (N) |

Response rate among the candidates (%) |

Number of respondents elected to the Seimas (N) |

Percentage of the respondents elected to the Seimas (%) |

The effective sample used in the study (N) |

|

2008 |

333 |

20 |

70 |

21 |

318 |

|

2012 |

295 |

15 |

48 |

16 |

286 |

|

2016 |

330 |

23 |

64 |

19 |

305 |

As suggested in the section on the partisan logic of the politics of memory, in our further empirical analysis, we use the concept of party families and produce a typology of four party families (Social Democrats, Conservatives, Liberals, and Populists41), i.e. we cover so-called mainstream parties and, thus, the mainstream electorate that reflects the general attitudes of the Lithuanian society. Jastramskis & Ramonaite highlight the prominence of the Social Democrats, Conservatives, and Populists on the Lithuanian political scene and draw attention to the consolidation of the Liberals.42 Jurkynas also discusses these four party groups as salient in Lithuanian parliamentary elections.43

The three consecutive sets of comparative data (cross-sectional research design) allow us to assess how (whether) the dominant frames of interpretation of past legacies and the public policy instruments designed to deal with them change and what (if any) variations in political party families’ profiles emerge (for the overview of indices used in the study, see Table 3).

Table 3. Overview of indices

|

Index |

Description |

Measurement |

|

Issue consistency |

This index reflects inter-item variation within each party family. |

The standard deviation of mean evaluations is the basis for the issue consistency score (lower scores indicate that a respondent has congruent attitudes towards all three issues measured, the lower the score, the greater the issue consistency). |

|

Party family coherence |

This index reflects the intra-group variation. |

The standard deviation of mean evaluations is the basis for the party family coherence score (lower scores indicate that the respondents from the same party family have congruent attitudes towards the issue). |

|

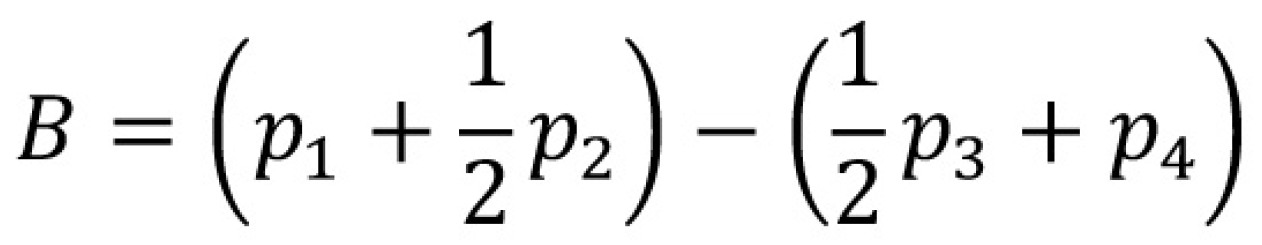

‘Soviet-conformist’ and ‘Soviet-punitive’ attitude measurement (balance score) |

This structuring dichotomy groups data on the axis ‘Soviet-conformist’ and ‘Soviet-punitive’. The category of ‘Soviet-punitive’ views is composed of those ‘Strongly agreeing’ and ‘Agreeing’ with the ideas that restrictions should be imposed on former KGB collaborators regarding holding positions in the civil service and education; that Soviet symbols should be banned; and that Lithuania should claim compensation from Russia for the damage inflicted by the Soviet occupation. Respectively, the category of ‘Soviet-conformist’ views is composed of those ‘Strongly disagreeing’ and ‘Disagreeing’ with the above listed ideas. |

The measurement is based on the balances, which are constructed as the difference between the percentages of respondents giving positive and negative replies. The balance score for the 4 item evaluation scale is calculated following the formula:

where B is the balance of opinions score (range from -100 to +100); P1 – the proportion of answers ‘Strongly agree’; P2 – the proportion of answers ‘Agree’; P3 – the proportion of answers ‘Disagree’; P4 – the proportion of answers ‘Strongly disagree.’ *Similar, survey-based indicators are used in the Consumer Confidence Index and in measuring expert opinion-based perceptions of international financial institutions such as the ECB. |

The analytical framework distinguishing the transitional, post-transitional and partisan logic that shapes the politics of memory provides clues about eventual shifts in direction, intensity, and cohesion of the politics of memory. The fading of political interest in memory issues would signal that the driving force of transitional fervor is expiring. Reinvigorated stances on the politics of memory would indicate the growing importance of a post-transitional logic, and a multi-dimensional structuration of elites’ views would reveal the partisan-ideological divides in the politics of memory.

Further, in the analytical part of the article we measure how (whether) elite attitudes towards the politics of memory are affected by two independent variables: belonging to the ‘party family’ and time. We expect ‘party family’ to have an effect on political candidates’ attitudes towards the politics of memory. As for the dimension of time, we control whether (and, if yes, then in which direction) there are any shifts in the positions of the political elite towards the politics of memory in elections 2008, 2012 and 2016.

3. Results and interpretations

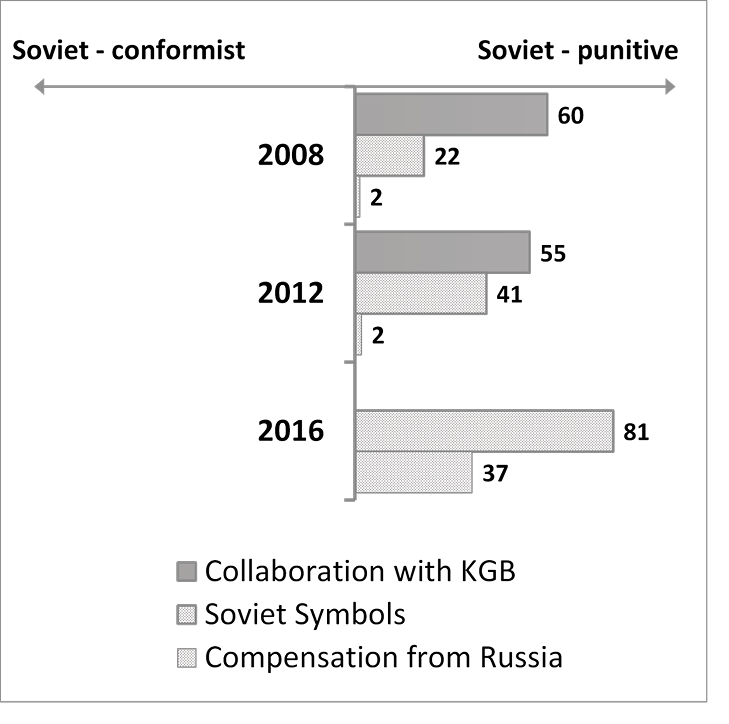

The first general observation is that Lithuanian parliamentary candidates do not populate the whole range of the scale from strongly punitive to strongly conformist and forgetful attitudes. They rather cluster around moderate conformist and moderately–strongly punitive stances towards the Soviet past (see Figure 1). The phenomenal absence of the strongly conformist attitudes towards the Soviet past can be traced back to the founding moment when strongly pro-Soviet stances were discredited by then-pro-Kremlin/USSR-oriented Lithuanian communists, including the defeated instigators of the attempted putsch and bloodshed in January 1991.

Figure 1. Overall dynamics of parliamentary candidates’ views. Balance scores in 2008–2016 (2008 N = 318, 2012 N = 286, 2016 N = 305).

* Balance score ranges from –100 to +100.

The shift observed in 2008–2016 towards more radical punitive positions on the opinion balance score vis-à-vis the removal of Soviet symbols from public spaces clearly contradicts the transitional logic (dismissing H1), eventually leading to a calmer politics of memory. Yet, the underlying transitional logic (supporting H1) is detected in candidates’ views on lustration, generating less punitive attitudes. For 2016, the data on this issue is not available, however, the issue of lustration is far from disappearing from the political agenda. In 2018, an amendment to the lustration law was proposed, it would have guaranteed that the information about citizens who have dully declared their former collaboration with the KGB would be kept sealed for the period of 75 years.

Meanwhile, we see a substantial radicalization of punitive views on the public display of Soviet symbols, thus indicating the post-transitional propensity (supporting H2) to revise and reaffirm the politics of memory. Post-transitional logic is also supported by the increase of radical stances towards the compensation from Russia issue.

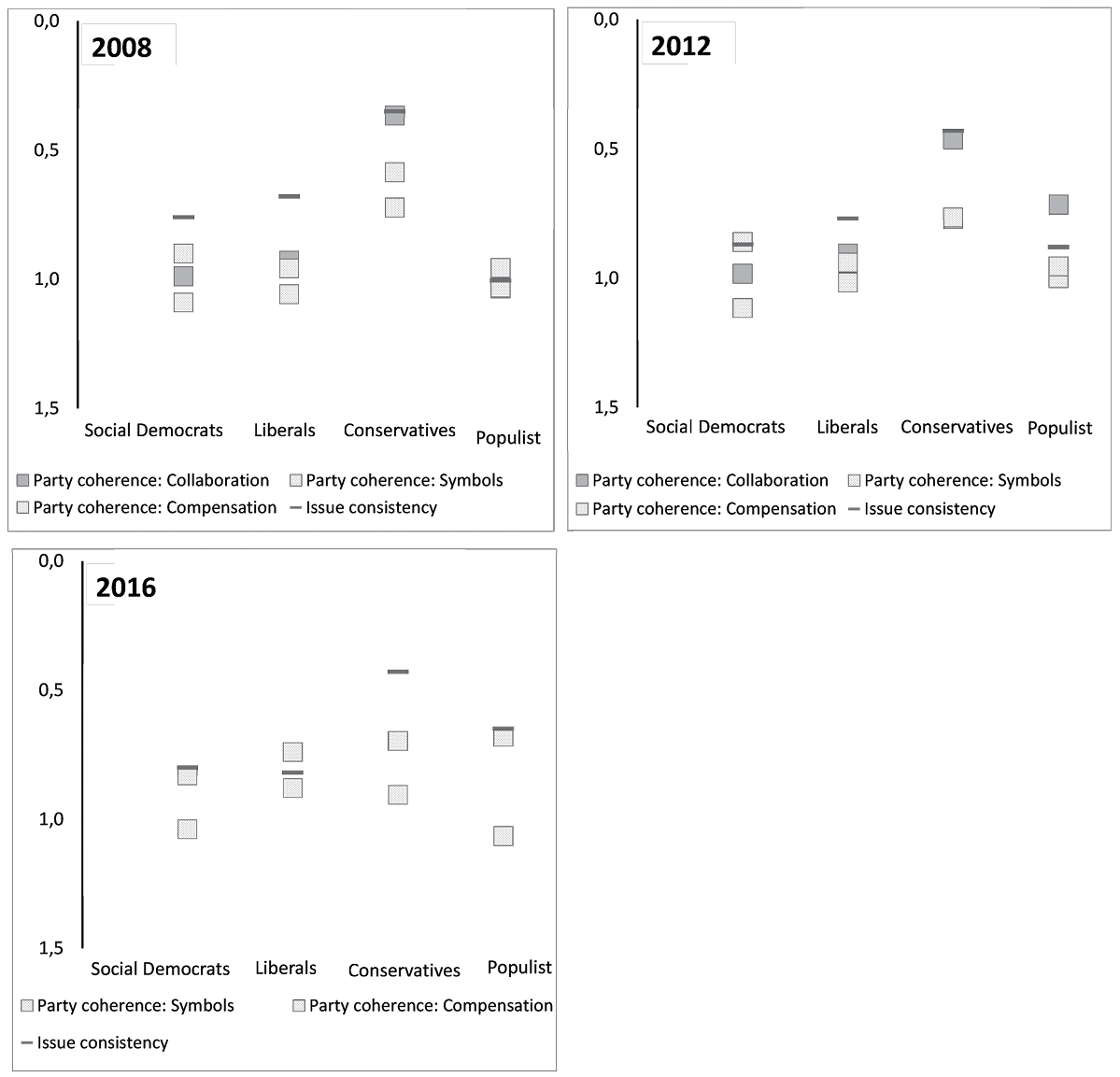

Figure 2 shows data distinguishing different patterns of stability and change in party-family coherence and issue consistency during 2008–2016. H3 is largely confirmed: political party families differ in their attitudes towards the politics of memory. The Lithuanian Conservatives stand out as the party family with the most coherent views towards all three selected issues of the politics of memory and the issue consistency among their elites is the highest. The views of Liberal family elites are also quite issue-consistent. However, the intra-party family coherence of Liberal views is not high. Issue consistency among Social Democrats is noticeably lower. Their intra-party family coherence is only moderate. The Populists have remarkably inconsistent and incoherent views on the politics of memory. During 2008–2016, their scores on issue consistency and intra-party family coherence marginally increased. For them, the issue of lustration (on which their conformist stances increased in 2012) stimulated higher intra-party family coherence. Two Populist leaders in 2008 were accused of collaboration with the KGB, but later they were cleared of these allegations. Populist stances regarding the public display of Soviet symbols became more punitive in 2016.

Therefore, H4 is only partially confirmed, since – with the exception of the Conservatives – the coherence and consistency of all the other party families’ stances on the politics of memory vacillate noticeably. In 2016 all party families display the highest coherence with regard to the display of Soviet symbols (their removal). Consistency of liberal views decreased in 2016 and significantly increased among Populists. During 2008–2016, the Social Democrats proved to be the least ‘mobile.’

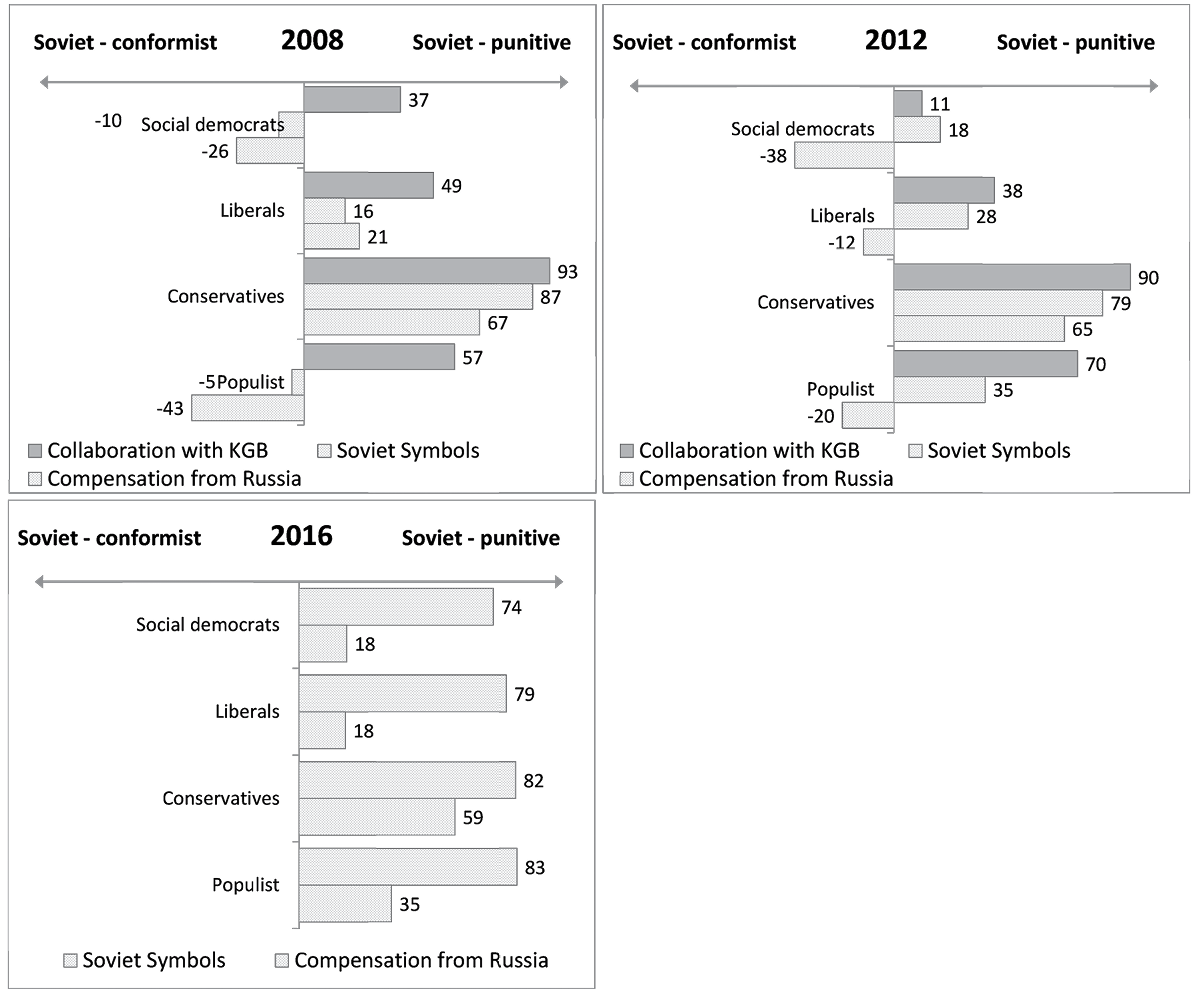

Figure 2. Intra-party family coherence and issue-consistency by party families (2008 N = 318, 2012 N = 286, 2016 N = 305).

Partisan differences can be seen in the variations of attitudes towards all three selected issues. In the case of three out of four party families, the patterns change significantly from one electoral period to another (Figure 3). While analyzing data from 2016, we should consider the change in the geopolitical situation (the annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014) and the increase of threat perceptions. In 2016, the attitudes towards the memory questions related to Russia undergo radical change: Populists along with Conservatives become the most ardent advocates of the demands for compensation from Russia. Compared to 2008–2012, in 2016, all the four party families ‘revise’ their attitudes and on all memory accounts switch to punitive stances. In 2016, the issue of Soviet symbols ceases to polarize the Lithuanian political life: all four party families become highly punitive (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Patterns and dynamics of party families’ views. Balance scores in 2008–2016 (2008 N = 318, 2012 N = 286, 2016 N = 305).

* Shifts in the politics of memory among party families during the 2008–2016 period.

** Balance score ranges from –100 to +100.

Conservatives display their strongly punitive attitudes towards all three selected issues: collaboration with the KGB, Soviet symbols, and compensation from Russia. As anticipated by H4, in terms of the politics of memory, the Conservatives are programmatic and do not mold and refashion their electoral stances.

The Liberals advance overall moderately punitive stances. However, the Liberal’s attitudes are dynamic and change significantly from one election campaign to another. Opportunistic, strategic, and tactical calculations form the basis of the Liberals’ attitudes towards the politics of memory. If, in 2008, the Liberals were moderately punitive on all three selected issues, they became more conformist and accommodating on the issue of compensation from Russia in 2012. In 2016 the punitive stances among Liberals further radicalized. The changes in the Liberals’ stances on the politics of memory contradict H4. However, given that Liberals are relatively younger and less entrenched as a party family in Lithuania, these changes might also be understood as a revision of their programmatic stances.

The Social Democrats are ambivalent and dynamic in their attitudes towards the politics of memory. On the issue of collaboration with the KGB, they are moderately punitive (of all party families, the Social Democrats always were the least supportive of lustration). The Social Democrats were conformist in 2008 in relation to Soviet symbols, but later became more restrictive. However, in 2012, they became even more conformist towards the claim that Russia should compensate for Soviet damage. This contradictory move (towards a more restrictive stance in relation to Soviet symbols and towards a more conformist position in relation to compensation from Russia) in 2008–2012 shows that Social Democrats instrumentalize the politics of memory and do not relate it to programmatic party family positions. Thus, the case of the Social Democrats contradicts H4.

The Populists as a political group have remarkably contradictory views. They are rather (and increasingly) supportive of lustration. However, they are moderately conformist when it comes to compensation from Russia. During the electoral campaign for the Presidency of the Republic in spring 2019, the candidate of the Lithuanian Green and Farmers’ Party LVŽS declared that better relations with Russia are in ‘our interest.’ The Populists’ attitudes towards Soviet symbols are malleable: from moderately conformist in 2008 they shift to restrictive in 2012 and to harshly punitive in 2016 (on this account exceeding the Liberals and approaching the stance of Conservatives). Similarly, as in the case of Social Democrats, this dynamic of Populists’ attitudes is to be interpreted as an instrumentalization of the past during election campaigns (contradicting H4). This trend testifies to the nonprogrammatic characteristics of the Populists, who act as opportunistic communicators.

The shifts in radicalization (or de-radicalization) of the partisan politics of memory in 2008–2016 are visualized in Figure 3: the softened positions are indicated on the left side of the scheme, while radicalization can be seen on the right side. Comparisons in 2008–2016 by party families show the overall shift towards more moderate evaluations of the Soviet past (consistently with transitional logic, i.e. as H1 predicts) among the Conservatives, Social Democrats, and Liberals. The Populists are an exception to this trend: their positions became more radical on all three issues.

In support of H2, the attitudes of the four party families towards Soviet symbols and compensation from Russia for Soviet occupation stand out as very specific and they radicalize across the political spectrum in Lithuania in 2012–2016.

The empirical evidence suggests that parliamentary candidates do not treat the various aspects of the politics of memory as an aggregate issue. Their attitudes towards the three selected issues relevant to the politics of memory are dynamic and malleable. Lustration remains salient and, on this issue, the majority of the parliamentary candidates express punitive views.

The attitudes towards compensation from Russia for damage inflicted by the Soviet occupation are rather perplexing. In this respect, it is important to note that such claims bypass and transcend the domestic political market and deal with bilateral and international relations as well as with transnational discourses. In 2008, the Conservatives and Liberals, articulating their stances around the politics of rupture and maintaining a firm orientation towards the West, were the most vocal in demanding compensation from Russia, while the Social Democrats and Populists favored less demanding stances. The data from 2012 show an overall softening (de-radicalization) of demands for compensation from Russia and a more conformist and less coherent positions on this issue. These trends support the transitional logic hypothesis (H1) and partially support the hypotheses of partisan differentiation (H3) and the partisan programmatic approach (H4). However, in 2016 all tables are turned upside down as Russia’s war in Ukraine newly reinvigorated politics of memory.

Parliamentary candidates’ opinions on the ban of public display of Soviet symbols follow an exceptional path and support H2. Back in 2008, moderately conformist opinions about Soviet symbols were registered across the political spectrum, but the radicalization and hardening of stances towards this issue in 2008–2012 represented a trend that contrasted with the general trend of softening (less radical) attitudes towards collaboration with the KGB and compensation from Russia. It is notable that none of the party families moved in the direction of ‘de-criminalization’ and acceptance of Soviet symbols. The issue of Soviet symbols, which is rather abstract and easy to manipulate (i.e. it does not cause any direct damage to any social group and/or international actor), becomes more prominent in the politics of memory. Meanwhile, the issues of compensation from Russia and lustration, with their more tangible scope, tended to become less vibrant in 2012. However, in 2012–2016 all memory issues became securitized and reactivated among the Lithuanian political elites, threatened by Russia’s will to re-write the history and to renew its imperialistic policies, even by military force as demonstrated in Ukraine since 2014.44

Conclusions and perspectives for future research

The analysis reveals that, using the typology of mnemonic actors developed by Bernhard and Kubik that distinguishes mnemonic warriors, pluralists and abnegators,45 the politics of memory in Lithuania is dominated by mnemonic warriors joined by a chorus of more permissive pluralists, whose voices were heard in 2012 (only). Since the early 90s, punitive, harsh and intensive official appraisal of communism, the mnemonic warriors continue playing an important role in shaping collective memory in post-communist Lithuania. The seemingly ‘external’ event (Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and war in Ukraine) reactivated sensibilities of Lithuanian collective memory.

These geopolitical shifts perceptibly shattered the Liberals, who as a specific mnemonic community used to be rather permissive in their politics of memory, but in 2016, they became especially punitive. The radicalization of Liberals is reflected not only in their parliamentary candidates’ attitudes but also in the liberal politicians’ engagement into ‘symbolic exorcism,’46 as witnessed by the removal of the Soviet Statues from the Green Bridge in Vilnius.

The mnemonic community of Conservatives, harboring quite a few Soviet dissidents, former political deportees, and other victims of Soviet repressions, dwells on confrontationist strategies and promotes the ‘politics of anamnesis,’47 cultivating complex ways of remembering in a post-colonial society which ‘naturally’ tends to overlook, disavow, or repress memories of violence and local knowledge. The harsh and intensive politics of memory continues forming the ideological backbone of Lithuanian Conservatives.

Concerning the mnemonic community aspect, the ex-nomenklatura and former Communist party members are most typically found among Social Democrats. This structural feature helps when explaining more conformist attitudes towards the Soviet past in their ranks. As Tileagă explains, the ‘notion of conformity goes with the terms of cognitive dissonance and selective remembering.’48 Even though coherent ‘conformist’ public discourse is not produced by Social Democrats, yet, on the level of individual attitudes they stand out as inducing to less punitive practices and relations that people themselves make relevant in the course of confronting different aspects of their own past, or of that of their in-group members. To characterize Populists as a specific mnemonic community is difficult.

Getting back to the typology, proposed by Bernhard and Kubik, the third type of mnemonic actors, the abnegators, who would advance explicitly forgetful and conformist stances and radically deny the injustices of the Soviet past,49 has not been vocally represented in Lithuanian election campaigns. Presumably, this state of affairs shows that political elites in a post-communist democracy (Lithuania) effectively reduce the scope of the politics of memory. This finding also indicates a substantial potential for eventual post-transitional revisions of the politics of memory, engaging domestic and transnational civil society.

As to temporalities, which guide the politics of memory, our study illustrates how intricately several layers of temporalities are interwoven. Comparative data from electoral campaigns of 2008 and 2012 reveal that the dominant trend lends itself to the transitional logic of de-radicalization in the politics of memory. However, the abrupt changes in the Lithuanian geopolitical environment after the annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014 triggered the radicalization of punitive anti-Soviet stances and aroused collective memories of the traumatic past.

The increase in issue consistency and intra-party family coherence during the consecutive electoral periods of 2008, 2012 and 2016 indicates that besides the transitional logic there is evidence that parliamentary candidates are also inclined to operate following partisan logic. Conservatives represent a rather exceptional programmatic specimen that maintains consistent and coherent views towards the politics of memory. Obviously, deeper research into eventual differences and tensions in the frères-enemies parties in the same party family might shed more light on how that affects (or does not affect) the coherence and consistency of partisan stances towards the politics of memory. Party by party (not party family) approach in future research might offer interesting insights. This avenue for future research is especially attractive in the case of the Populist family, which widely engages into the personalization of electoral campaigns and expands its electoral shares assembling unconventional political actors.

The data on the dynamics of attitudes towards the politics of memory within other than Conservative party families reveal that parties are predisposed to act as strategic players and to manipulate the politics of memory. The Populists are particularly inclined to use the politics of memory for the purposes of electoral mobilization. The Social Democrats and Liberals also engage in electoral engineering. Both party families tend to abandon the issues of lustration, but their public stances on compensation from Russia and on Soviet symbols become more radical. However, we must remind the limitations of our data: the absence of ethnic political parties in the sample limits a comprehensive enquiry into programmatic and strategic partisan logic in the field of memory politics.

Summing up the findings in the case study of post-communist Lithuania, we can conclude that in the elite-driven politics of memory, the transitional effects up to 2012 were the most salient, but after 2016 they changed to post-transitional. Partisan tactical logic finds ample reflection in a selectively growing interest in bans on Soviet symbols while the signs of post-transitional logic are increasingly revealed by perceived fragility of the sovereign state. Our research does not support the arguments of a post-transitional calmer emotional context,50 but – on the contrary – reveals that political relevance of the memory of communism is ongoing.

References

Bernhard, Michael & Jan Kubik. Twenty Years after Communism: The Politics of Memory and Commemoration. Oxford University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199375134.001.0001

Dae, Soon Kim & Nigel Swain. “Party Politics, Political Competition and Coming to Terms with the Past in Post-Communist Hungary.” Europe-Asia Studies 67, no. 9 (2015): 1445–1468. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2015.1087969

David, Roman. Lustration and Transitional Justice Personnel Systems in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812205763

David, Roman. “The Past or the Politics of the Present? Dealing with the Japanese Occupation of South Korea.” Contemporary Politics 22, no. 1 (2016): 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2015.1112953

Elster, Jon. Closing the Books: Transitional Justice in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511607011

Eglitis, Daina & Laura Ardava. “Remembering the Revolution: Contested Pasts in the Baltic Countries.” In Twenty Years after Communism. Edited by Michael Bernhard & Jan Kubik (pp. 123–145). New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199375134.003.0007

Gnatiuk, Olexiy. “The Renaming of Streets in Post-Revolutionary Ukraine: Regional Strategies to construct a New National Identity.” Acta Universitatis Carolinae Geographica 53, no. 2 (2018): 119–136. https://doi.org/10.14712/23361980.2018.13

Horne, Cynthia. “Lustration, Transitional Justice, and Social Trust in Post-Communist Countries. Repairing or Wrestling the Ties That Bind?” Europe-Asia Studies 66, no. 2 (2014): 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2014.882620

Ivanauskas, Vilius. “Ne už tokią Lietuvą dėjome parašą: posovietinės Lietuvos kultūrininkų praregėjimo, kaltės ir atsinaujinimo trajektorijos.” Darbai ir dienos 62, no. 2 (2014): 209–227. https://eltalpykla.vdu.lt/1/567

Jastramskis, Mažvydas & Ainė Ramonaitė. “Lithuania.” European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 56, (2017):176–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/2047-8852.12165

Jurkynas, Mindaugas. “The Parliamentary Election in Lithuania, October 2012.” Electoral Studies 34 (2014): 334–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2013.08.019

Karpavičiūtė, Ieva. “Securitization and Lithuania’s National Security Change.” Lithuanian Foreign Policy Review 36 (2017): 9–32. https://doi.org/10.1515/lfpr-2017-0005

Kiss, Csilla. “The Misuses of Manipulation: The Failure of Transitional Justice in Post-Communist Hungary.” Europe-Asia Studies 58, no. 6 (2006): 925–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130600831142

Kritz, Neil. “Policy Implications of Empirical Research on Transitional Justice.” In Assessing the Impact of Transitional Justice: Challenges for Empirical Research. Edited by Hugo Van der Merwe, Victoria Baxter, & Audrey Chapman (pp. 13–22). United States Institute of Peace, 2009.

Lašas, Ainius. European Union and NATO Expansion: Central and Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230106673

Lieven, Anatol. The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Path to Independence. Yale University Press, 1993.

Mano balsas (2008–2019). Available at: www.manobalsas.lt (accessed 4 April 2023).

Matonytė, Irmina. “The Elites’ Games in the Field of Memory: Insights from Lithuania.“ In History, Memory and Politics in Central and Eastern Europe Memory Games. Edited by Georges Mink & Laure Neumayer (pp. 105–120). Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Matonytė, Irmina & Gintaras Šumskas. “Lithuanian Parliamentary Elites after 1990: Dilemmas of Political Representation and Political Professionalism.” In Parliamentary Elites in Central and Eastern Europe: Recruitment and Representation. Edited by Elena Semenova, Michael Edinger & Heinrich Best (pp. 145–168). Routledge, 2014. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315857978.

Mink, Georges & Laure Neumayer. (Eds.). History, Memory and Politics in Central and Eastern Europe Memory Games. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Nalepa, Monika. Skeletons in the Closet: Transitional Justice in Post-Communist Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815362

Neumayer, Laure. “Integrating the Central European Past into a Common Narrative: The Mobilizations around the Crimes of Communism in the European Parliament.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 23, no. 3 (2015): 344–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2014.1001825

Onken, Eva-Clarita. “The Baltic States and Moscow’s 9 May Commemoration: Analysing Memory Politics in Europe.” Europe-Asia Studies 59, no. 1 (2007): 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130601072589

Perchoc, Philippe. “Un passé, deux assemblées. L’assemblée parlementaire du Conseil de l’Europe, le parlement européen et l’interprétation de l’histoire (2004–2009).” Revue d’Etudes Comparatives Est-Ouest 45, no. 3–4 (2014): 112–138. https://doi.org/10.4074/S0338059914003088

Pettai, Eva-Clarita & Vello Pettai. Transitional and Retrospective Justice in the Baltic States. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Pettai, Eva-Clarita. “Debating Baltic Memory Regimes. A Discussion of Michael Bernhard and Jan Kubik: Twenty Years after Communism. The Politics of Memory and Commemoration.” Journal of Baltic Studies 47, no. 2 (2016): 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629778.2015.1108347

Raimundo, Filipa. “Dealing with the Past in Central and Southern European Democracies: Comparing Spain and Poland.” In History, Memory and Politics in Central and Eastern Europe Memory Games. Edited by Georges Mink & Laure Neumayer (pp. 136–154). Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Ramonaitė, Ainė. “Mapping the Political Space in Lithuania: The Discrepancy between Party Elites and Party Supporters.” Journal of Baltic Studies 51, no. 4 (2020): 477–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629778.2020.1792521

Rusu, Mihai Stelian. “Transitional Politics of Memory: Political Strategies of Managing the Past in Post-Communist Romania.” Europe-Asia Studies 69, no. 8 (2017): 1257–1279. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2017.1380783

Saarts, Tonis. “Comparative Party System Analysis in Central and Eastern Europe: The Case of the Baltic States.” Studies of Transition States and Societies 3, no. 3 (2011): 83–104. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-363800

Sadowski, Ireneusz. “The Constant Electoral Flux? Party System and the Circulation of Candidates and Parliamentarians in Poland, 1989–2011.” International Journal of Sociology 48, no 1 (2018): 34–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2018.1414502

Semenova, Elena, Michael Edinger, & Heinrich Best. (Eds.). Parliamentary Elites in Central and Eastern Europe: Recruitment and Representation. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014.

Shabad, Goldie & Kazimierz Slomczynski. “Inter-Party Mobility among Parliamentary Candidates in Post-Communist East Central Europe.” Party Politics 10, no. 2 (2004): 151–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068804040498

Siddi, Marco. “The Ukraine Crisis and European Memory Politics of the Second World War.” European Politics & Society18, no. 4 (2017): 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2016.1261435

Stan, Lavinia. “Reckoning with the Communist Past in Romania: A Scorecard.” Europe-Asia Studies 65, no. 1 (2013): 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2012.698052

Tileagă, Cristian. Representing Communism after the Fall: Discourse, Memory, and Historical Redress. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97394-4

Verovšek, Peter. “Collective Memory, Politics, and the Influence of the Past: The Politics of Memory as a Research Paradigm.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 4, no. 3 (2016): 529–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2016.1167094

Žalimas, Dainius. “SSRS okupacijos žalos atlyginimo įstatymas ir Rusijos Federacijos atsakomybės tarptautiniai teisiniai pagrindai.” Politologija 4, no. 44 (2006): 3–53.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50