Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2023, vol. 14, no. 1(27), pp. 152–170 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2023.14.86

Low Consumer Social Responsibility Increases Willingness to Buy from Large vs. Small Companies

Elze Uzdavinyte (corresponding author)

ISM University of Management and Economics, Lithuania

Institute for Advanced Behavioral Research, AdCogito, Lithuania

elze.uzdavinyte@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1180-1404

Zivile Kaminskiene

ISM University of Management and Economics, Lithuania

Institute for Advanced Behavioral Research, AdCogito, Lithuania

zivile.kaminskiene@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2655-3570

Abstract. Previous research mainly concentrated on the link between the company size and consumer perceptions related to corporate social responsibility (CSR). Here we aim to extend the previous findings to the context of the consumer’s individual trait of social responsibility. Building on signaling theory, we analyze such signals as company size and demonstrate that consumers have a decreased willingness to buy a product originating from a large company as compared to a small company. However, the effect flips for consumers with low social responsibility as they show a higher willingness to buy large company products. We contribute to signaling theory by showing that consumer traits such as consumer social responsibility can play an important role in the effectiveness of the signal. In addition, these findings contribute to consumer social responsibility research as well as consumer behavior literature by showing that the company size effect is moderated by consumer social responsibility. Theoretical and managerial implications are discussed together with directions for future research.

Keywords: company size, willingness to buy, consumer social responsibility

Received: 24/1/2023. Accepted: 26/3/2023

Copyright © 2023 Elze Uzdavinyte, Zivile Kaminskiene. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Such terms as “Big Pharma” and “Big Tech” show that the adjective “big” has become more than a descriptor of company size but refers to the general demonization of large companies (Ovide, 2020; Thiessen, 2021). Indeed, sometimes large companies receive negative consumer evaluations and are seen as less ethical than small companies (Freund et al., 2023), less authentic (Özsomer, 2012), and tend to be associated with such wrongdoings as higher pollution (Grant et al., 2002) or illegal actions (Mishina et al., 2010). However, another line of research shows rather contradictory findings indicating consumers’ support for large companies (e. g., Bartsch et al., 2016) due to their superior quality, strong image, global appeal, conformity to consumption trends (Zhou et al., 2008; Strizhakova et al., 2008), or status and prestige (Davvetas & Diamantopoulos, 2016; Liu et al., 2021; Steenkamp, 2014).

As the previous research findings are mixed, it could be argued that there is an additional explanation that can elucidate why consumer support for large and small companies differs. One reason why consumers prefer small companies over large companies is related to the consumer tendency to evaluate small companies as more sincere (De Vries & Duque, 2018) or more trustworthy (Green & Peloza, 2014). Another explanation proposed by the previous research might be that consumer traits drive the company size effect (e. g., Thompson & Arsel, 2004; Paharia et al., 2011). Knowing that consumers show more favorable attitudes (Bhattacharya & Sen, 2004) and a willingness to pay a premium (Rahman & Norman, 2016) when a small locally-owned company is performing CSR and that small companies are de facto considered socially responsible compared to large companies (Green & Peloza, 2014), we propose that there is a trait linking company size and CSR – namely, consumer social responsibility, defined as the conscious and deliberate choice to make certain consumption choices based on personal and moral beliefs (Devinney et al., 2006).

Building on this knowledge, we propose that consumers will show a higher willingness to buy a small company’s product rather than a product originating from a large company and that the company size effect will flip for individuals with low consumer social responsibility as they will show a higher willingness to buy a product originating from a large company. This paper aims to contribute to the existing knowledge in four ways. First, even though the effect of the company size on consumer perceptions and decisions has been addressed in previous literature (e. g., Green & Peloza, 2014; De Vries & Duque, 2018; Uzdavinyte et al., 2023 under review), there is still little knowledge of the company size effect on a consumer’s willingness to buy, and our research aims to shed light on this phenomenon. Second, we analyze the company size effect in regard to signaling theory. Existing research analyzed competence and quality‐related signals (e. g., Boulding & Kirmani, 1993; Erdem & Swait, 1998, 2004; White &Yuan, 2012, Zhang & Wiersema, 2009) or signals related to the family nature of the company (Rauschendorfer et al., 2021). We aim to address these shortcomings by following the suggestion by Connelly et al. (2011) to explore different signals, precisely in reference to company size. Third, while the majority of research has concentrated on corporate social responsibility and how it impacts consumer behavior, this study looks into consumers and how their internal trait of social responsibility can affect their behavioral decisions. This is the first study that addresses the consumer social responsibility trait in the context of the company size signal and willingness to buy a product. We contribute to the signaling theory by showing that consumer traits such as consumer social responsibility can play an important role in the effectiveness of the signal. Furthermore, we aim to reconcile the contradictory findings of previous research by showing that consumer support for different company sizes depends on the consumer’s internal trait of social responsibility. Finally, our findings provide insights for marketers by showing that it is not only company attributes, in this case company size, that matter to consumer decisions, but also how intrinsic individual traits such as consumer social responsibility can affect consumer intentions. We discuss how this knowledge might enable practitioners to tailor specific communication messages for different consumers.

1. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

1.1 Organizational Stereotypes and Signaling Theory

Stereotypes are conceptualized as evaluations about an individual or entity, such as a company, based on its membership in a specific category (Dovidio & Gaertner, 1993). Recent research has identified one fundamental characteristic that shapes judgments, namely company size (Freund et al., 2023), as an important category used for evaluation and classification of organizations (Hall et al., 1967; Kimberly, 1976). Company size may refer to different measures such as the number of employees, market share, or value of the company. Though small companies are sometimes associated with locally based organizations (e. g., Rahman & Norman, 2016; Paharia et al., 2014), and large companies are often understood as multinational corporations (e. g., Baumann-Pauly et al., 2013; Rahman & Norman, 2016; Jamali et al., 2009), in this research we conceptualize small and large companies in terms of the number of employees, market share, and product assortment (see Appendix A).

A tendency to form certain expectations and perceptions driven merely by the signal of a company’s size has been noted before. For instance, small companies are seen as more capable of developing close and direct relationships with their customers (Spence, 1999), more trustworthy (Green & Peloza, 2014), more communal (Yang & Aggarwal, 2019), and more sincere (De Vries & Duque, 2018). Consumers support small companies for several underlying reasons: willingness to emphasize their beliefs regarding anti-commercialization (Thompson & Arsel, 2004), a tendency to identify with underdogs (Paharia et al., 2011), or a consumer’s quest for authenticity (Newman & Bloom, 2012).

Given the variety of different research related to the company size effect on consumer perceptions and evaluations, it is still unclear what can be the underlying theory explaining why small and large companies garner such differing support from consumers. Our suggestion is signaling theory with its core idea that one party credibly conveys some information about itself to another party (Spence, 1973). Applied in a wide variety of disciplines and different contexts (Smith & Bliege Bird, 2005), signaling theory was also tested in consumer behavior research (Boulding & Kirmani, 1993; Erdem & Swait, 1998, 2004; White & Yuan, 2012). Previous research has noted various signaling effects on consumer perceptions and evaluations. For instance, the extrinsic signals of price or warranties are used by consumers as “signals” of product quality (Wright 1986; Zeithaml 1988; Boulding & Kirmani, 1993). Brand credibility signals affect consumer choices and brand consideration (Erdem & Swait, 1998). More recent research by Rauschendorfer et al. (2021) shows that consumers consider a product signaling the family nature of a firm to be made with love and are willing to pay a price premium.

We apply signaling theory as a framework for our argument that the company size signal plays an important role in forming a consumer’s willingness to buy. Our research model is comprised of the independent variable of company size (small vs. large) representing the signal, the dependent variable of the willingness to buy (the intention formed by the receiver of the signal) and the moderator of consumer social responsibility. We aim to contribute to signaling theory by showing that consumer traits such as consumer social responsibility can play an important role in the effectiveness of the signal.

Figure 1

Research Model

1.2 Company Size Effect on Willingness to Buy

Previous research has demonstrated that company size affects consumer expectations (Yang & Aggarwal, 2019) and perceptions (Green & Peloza, 2014; De Vries & Duque, 2018). Moreover, company size has become an important factor in consumer purchase behavior. For instance, consumer preference for large brands declines, and preference for small brands boosts when these two brands are framed to be competing against each other (Paharia et al., 2014). Consumers are motivated to have an impact on the marketplace as a result of the competitive context of conditions; consumers’ support for large companies declines, and it manifests as decreased purchase intentions, lower real purchases, and less favorable online reviews (Paharia et al., 2014). In addition, some consumers do not identify with large companies, as small underdog brands are better at addressing their identity needs (Paharia et al., 2011). Also, recent research has demonstrated that the large company size signal leads to a decreased perception of product healthiness, and this in turn decreases consumer willingness to buy that product (Uzdavinyte et al., under review). Building on this knowledge, we expect that:

H1: A large company signal (vs. a small company signal) leads to a decreased willingness to buy a product.

1.3 Corporate Social Responsibility and Company Size

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a well-known concept defined as a “firm’s considerations of, and response to, issues beyond the narrow economic, technical, and legal requirements of the firm to accomplish social [and environmental] benefits along with the traditional economic gains which the firm seeks” (Davis, 1973). The European Commission has defined CSR as “the responsibility of enterprises for their impacts on society” (2011). Consumer preference for companies showing CSR behavior has been well documented (Murray & Vogel, 1997; Mohr & Webb, 2005; Becker-Olsen et al., 2006). CSR improves company image and product evaluations (Brown & Dacin, 1997), and increases purchase intentions (Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001; Lee & Shin, 2010). Meanwhile, sometimes consumers also tend to punish companies that exhibit corporate social irresponsibility (Grappi et al., 2013; Sweetin et al, 2013; Valor et al., 2022). Previous research agrees that CSR is an important factor, and consumer awareness of CSR is growing (Jung et al., 2022; Field, 2021). However, sometimes consumers form CSR-related perceptions based on information about the company size (Green & Peloza, 2014).

CSR and company size links have been investigated previously both in emerging economies (Aras et al., 2010; Dartey-Baah & Amoako, 2021) and developed markets ( Green & Peloza, 2014), but knowledge in this area is still scarce as large multinational companies have been the center of attention when discussing the topic of CSR (Rahman & Norman, 2016; Spence, 2007). However, small companies also deserve the spotlight as CSR has not been extensively studied before, and small companies contribute a significant part of economic value (Jamali et al., 2009). Previous research has shown that consumers respond positively when a relatively small company behaves in a way that is beneficial to the community (Miller, 2001; Rahman & Norman, 2016; Bhattacharya & Sen, 2004). Also, consumers have greater trust in small rather than large companies (Green & Peloza, 2014) and perceive small companies engaging in cause-related marketing as exerting greater effort compared to large companies, and this leads to small companies being perceived as more sincere (De Vries & Duque, 2018). When small locally owned companies conduct CSR, consumers show more favorable attitudes (Bhattacharya & Sen, 2004) and a willingness to pay a premium (Rahman & Norman, 2016). Furthermore, some scholars even propose that small companies are de facto considered socially responsible compared to large companies merely because of their size (Green & Peloza, 2014). Indeed, research supports the notion that smaller companies are strong in implementing CSR-related practices in their business operations (Baumann-Pauly et al., 2013). Moreover, as small companies often operate in local communities, such moral proximity to the community stimulates a firm’s engagement in socially responsible actions (Spence, 2004).

1.4 Consumer Social Responsibility

While research on CSR has been extensively analyzed, very little attention has been paid to the consumers themselves and how they differ in terms of their attitudes towards social responsibility (Schlaile et al., 2018; Caruana & Chatzidakis, 2014; Quazi et al., 2016). Webster (1975) made the first attempt to define a socially responsible consumer as “a consumer who takes into account the public consequences of his or her private consumption or who attempts to use his or her purchasing power to bring about social change (p. 188)”. Later definitions followed as “ones who purchase products and services perceived to have a positive (or less negative) influence on the environment or who patronize businesses that attempt to affect related positive social change” (Roberts, 1993, p 140) or as “a person basing his or her acquisition, usage and disposition of products on a desire to minimize or eliminate any harmful effects and maximize the long term beneficial impact on society” (Mohr et al., 2001, p. 47). Researchers agree that consumers demonstrate an increasing interest in CSR initiatives (Jung et al., 2022; Durif et al., 2011), however, the concept of a socially responsible consumer has been largely unexplored (Caruana & Chatzidakis, 2014).

Previous research notes that socially responsible consumers are essential for corporate social responsibility to thrive (Vitell, 2015) and play a significant role in ensuring the success of social initiatives undertaken by businesses leading to economic gains (Quazi et al., 2016). For example, consumers who respond favorably to CSR activities are the ones who are more eager to consume responsibly themselves (Mohr & Webb, 2005; Öberseder et al., 2011).

Hypothesis 1 states that exposure to a large company signal (vs. a small company signal) leads to a decrease in consumer willingness to buy a product. However, this process will likely be not uniformly evident for everyone. According to the Conscious Consumer Spending Index, 64% of consumers supported socially responsible brands in 2021 (Field, 2021) demonstrating an increasing interest in CSR initiatives by consumers (Jung et al., 2022). However, there is still a considerable share of consumers (based on the recent data, 36%) with a low level of concern for CSR initiatives (Roberts, 1993; Belk et al., 2005; Pomering& Dolnicar 2009; Öberseder et al., 2011; Stankovic, 2019). Previous research provided evidence that consumers who are not socially responsible tend to justify themselves by pointing out that large companies are also replete with ethical abuses (Belk et al., 2005). We try to extend this notion by proposing that consumers with low social responsibility not only justify their lack of responsibility but they also are willing to buy products from large companies more than from small ones as it suggestively is more in line with their own values. Building on these notions, we propose that:

H2: A large company signal (vs. a small company signal) leads to an increased willingness to buy for consumers with low social responsibility.

2. Methodology, Data Collection and Results

2.1 Overview of Empirical Research

We carried out two experiments to test the impact of the company size signal on the willingness to buy a product. We also investigated the nature of this effect by addressing the role of consumer social responsibility. The hypotheses were tested with different product categories (water bottles and smoothies). By manipulating company size, we expect that a large company size signal will decrease consumer willingness to buy a product as compared to a small company size signal (H1). Using a different product, Experiment 2 aims to test if the company size effect on willingness to buy is moderated by a consumer’s social responsibility. Specifically, we expect that consumers with low social responsibility will demonstrate a higher willingness to buy a product from a large company rather than a small company (H2).

2.2 Experiment 1

Experiment 1 aims to show the initial effect of a company size signal on the willingness to buy a product. We expect that a large company signal (vs. a small company signal) will lead to a lower willingness to buy a product.

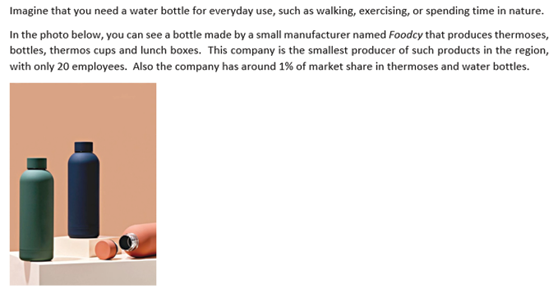

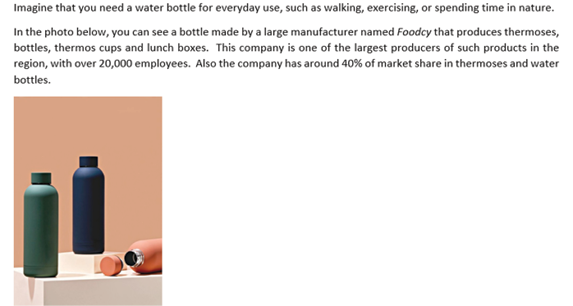

Method and measures. 400 adult participants were recruited from a professional research agency based in a mid-sized European country, Lithuania (Mage = 49.5 years, SD = 17.61, 55% female). The design was a single-factor experiment with three-levels (small vs. medium vs. large of the company size signal; the dummy coded large company signal being the reference condition; 0 = small, 1 = large, medium = 2). The participants were randomly assigned to read one of the three experimental conditions about a company producing water bottles and thermoses and were shown a picture of the water bottle that they make. In the large company condition, participants read: “In the photo below, you can see a bottle made by a large manufacturer named Foodcy that produces thermoses, bottles, thermos cups and lunch boxes”. While in the small company condition, they read: “In the photo below, you can see a bottle made by a small manufacturer named Foodcy that produces thermoses, bottles, thermos cups and lunch boxes”. In the medium-sized company condition, they read: “In the photo below, you can see a bottle made by a medium-sized manufacturer named Foodcy that produces thermoses, bottles, thermos cups and lunch boxes” (for full wording of manipulations, see Appendix A).

Participants were asked to evaluate their willingness to buy the water bottle shown in the picture using a five-item 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = ‘totally disagree’ to 7 = ‘totally agree’ (adapted from Dodds, Monroe, & Grewal, 1991), Cronbach’s α = 0.92; M = 3.20; SD = 1.44, see Appendix B, sample item: If I were going to buy a water bottle, I would consider buying this one) with higher scores representing a higher willingness to buy the product.

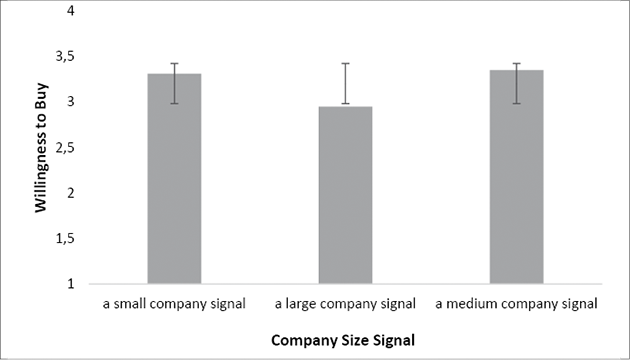

Results. To assess if the manipulation of the company size signal was successful, we asked if participants recalled what kind of company was described at the beginning of the questionnaire and asked them the following question: “How big is the company described in the text? 1 – not big at all, 7 – very big”. The company size signal manipulation was successful as respondents evaluated the large company condition to be significantly larger than the condition of the small company (Mlarge = 5.93, SDlarge = 1.23 vs. Msmall = 1.65, SDsmall = 1.05, t(264) = 30.58, p <.001) or medium-sized company

(Mmedium = 3.78, SDmedium = 1.38, t(265) = 13.43, p<.001).

To test the effect of the company size signal on the willingness to buy the product, an independent sample t-test was conducted. The result indicates a main effect t(264) = - 2.07, p = .04, so that the willingness to buy a water bottle from a large company is significantly lower than the willingness to buy the identical product from a small company (Mlarge = 2.95, SDlarge = 1.41, Msmall = 3.31, SDsmall = 1.41, see Figure 1). In addition, the willingness to buy a water bottle from a large company is significantly lower than the willingness to buy an identical product from a medium-sized company (Mlarge = 2.95, SDlarge = 1.41, Mmedium = 3.35, SDmedium = 1.49, t(265)= -2.28, p = .02). The result indicates no significant difference in the willingness to buy a product originating from small or medium-sized companies (Msmall = 3.31, SDsmall = 1.41; Mmedium = 3.35,

SDmedium = 1.49, t(265)= .26, p = .80).

Figure 1

Company Size Signal (Large vs. Small vs. Medium) Effect on Willingness to Buy

Discussion. Experiment 1 shows that the company size signal has an effect on consumers’ willingness to buy the product. Specifically, a large company signal (vs. a small company signal) decreases consumers’ willingness to buy it, hence supporting H1.

1.3 Experiment 2

Experiment 2 aims to expand the results reported in Experiment 1, by using another product, “fruit smoothie”. In addition, we test the consumer social responsibility trait as a moderator of the company size effect on the willingness to buy the product.

Method and measures. We used the Prolific Academic online panel to recruit UK participants in exchange for a small monetary payment. We did not analyze the responses of any participants who never buy smoothies. Thus, we used the responses of a sample of three hundred forty-three participants for further analysis (Mage = 37.76 years, SD = 12.68, 49.9% female).

The design was a single-factor experiment with a four-level (small vs. large vs. medium vs. control company size signal; dummy variable was coded as 0 = control, 1 = small, 2 = large, 3 = medium). The participants were randomly assigned to read one of the four experimental conditions (see Appendix A).

Willingness to buy was measured using a three-item 7-point Likert scale (adapted from Aaker & Keller, 1990; Taylor & Bearden, 2002), Cronbach’s α = 0.93, M = 4.38, SD = 1.35, sample item: I have the intention of buying this smoothie) with higher scores representing a higher intention to buy the product. Consumer social responsibility was measured using a 7-point Likert scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.81, M = 5.07, SD = 1.06, see Appendix B, sample item: In my opinion, I am a socially responsible person).

Results. We used the same manipulation check as in Experiment 1. The size manipulation was successful as respondents evaluated the small company condition to be significantly smaller than the large company condition (Msmall = 1.73, SDsmall = .96 vs. Mlarge = 5.71, SDlarge = 1.15; t(168) = - 24.53, p < 0.001) and significantly smaller than the control condition (Mcontrol = 3.68, SDcontrol = 1.16; t(175) = -12.25, p < .001) or medium condition (Mmedium = 3.49, SDmedium= 1.20; t(178) = -10.86, p < .001).

Next, we analyzed how a company’s size signal affects the willingness to buy the product. We found no significant differences in the willingness to buy from the small company vs the control (Msmall = 4.51, SDsmall = 1.38, Mcontrol = 4.29, SDcontrol = 1.46, t(175)= 1.07, p = .29), vs the medium (Mmedium = 4.23, SDmedium = 1.31, t(178)= 1.40, p = .16 ) or the large one (Msmall = 4.51, SDsmall = 1.38, Mlarge = 4.50, SDlarge = 1.22, t(168)= .09, p = .93) .

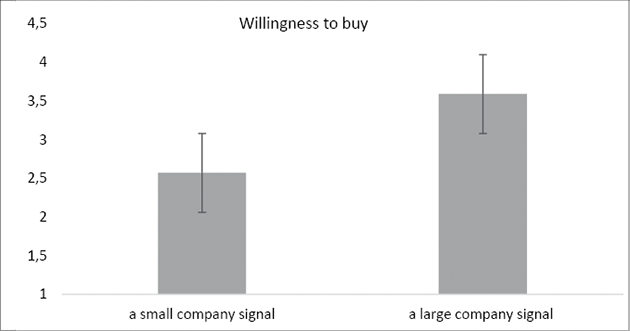

Moderation analysis. Using Model 1 (moderation) of Hayes’ (2022) PROCESS macro with 5,000 boot-strapped samples, we observed an interaction among the company size signal (small vs. large) and consumer social responsibility on the willingness to buy a fruit smoothie (B=.38. SE = 0.16, t(166)= 2.33, p = 0.02). Furthermore, individuals with low consumer social responsibility showed a higher willingness to buy the large company’s product as compared to the small company’s product (B= -1.02. SE = 0.50, t(166)= -2.05, p = 0.04).

Figure 2

Small vs Large Company Size Signal Effect on Willingness to Buy for Consumers with Low Social Responsibility

Discussion. Experiment 2 expands the findings reported in Experiment 1 by showing a boundary condition when the effect of the company size signal on the willingness to buy the product flips. In Experiment 2, we show that consumers with low social responsibility are more willing to buy the product originating from the large company as compared to the small one.

3. Theoretical Discussion

Grounded in signaling theory (Spence, 1973, 2002) through two online experimental studies with different products (a water bottle and a smoothie) in Lithuania and the United Kingdom, this research demonstrates that a large company signal (vs. a small company signal) leads to a decreased consumer willingness to buy. However, the effect flips for consumers with low social responsibility as exposure to a large company signal leads to a higher willingness to buy the product. These findings contribute to current knowledge in four ways. First, previous research applying signaling theory was focused on competence and quality‐related signals (Boulding & Kirmani, 1992; Certo et al., 2001; Certo, 2003; Connelly et al., 2011; Kharouf et al., 2020) or the signaling of the family nature of a company (Rauschendorfer et al., 2021). Following the suggestion by Connelly et al. (2011) to explore various signals more in-depth, we propose that signaling theory can be extended by analyzing such signals as company size. Second, we show that consumer traits such as consumer social responsibility can play an important role in the effectiveness of the signal. In addition, our research adds to the existing consumer behavior literature on the effect of the company size on consumer evaluations. Third, though the majority of previous research has been concentrated on the effect of CSR on consumer perceptions, very little attention has been paid to consumers themselves and how their internal trait of social responsibility affects their perception and behavioral intentions (Schlaile et al., 2018; Caruana & Chatzidakis, 2014; Quazi et al., 2016). Precisely, this research investigates consumer social responsibility and how it can affect consumer decisions. Fourth, our studies reconcile the contradictory findings of previous research by showing that the main driver for consumer support for different company sizes depends on the consumer’s internal trait of social responsibility.

4. Managerial Implications

The findings provide several important implications for marketers of both small and large companies. First, this research provides evidence that the company size signal matters to consumers, therefore, managers should pay attention to it when creating communication messages. Second, according to these research findings, the effect of the company size signal on the willingness to buy the product differs for different consumers. Specifically, the effect flipped for consumers with low social responsibility as they showed an increased willingness to buy from a large rather than a small company. Knowing that companies would not want to lose revenue it is recommended to target both the consumers with low and high social responsibility by tailoring specific communication messages. Even though segmenting consumers according to their consumer social responsibility attitude is rather difficult, it is a valuable approach (Öberseder et al., 2011). This strategy is the most relevant for online shopping platforms that digitally track consumer online behavior, segment consumers according to their online habits, and can adapt company communication messages to different consumer types such as consumers with low and high social responsibility. Thus, it is recommended that large companies provide company size information, while small companies conceal their size when creating communication messages aimed at consumers with low social responsibility.

5. Limitations and Direction for Future Research

Several limitations and suggestions for future research are proposed. First, in this research, we used products that were not positioned as sustainable or environmentally friendly. However, it might be that providing sustainability or environmental labels to consumers with low social responsibility could operate as a boundary condition and annul the large company size effect on the increased willingness to buy a product. Therefore, future research could test the generalizability of our findings and how the company size effect differs depending on products with sustainability information. In addition, our research did not consider the possibility that a company’s size might have influenced participants’ perceptions related to the product price that in turn could influence one’s willingness to buy it. Second, our research limitations include testing different products in two different markets (water bottle in the Lithuanian market and fruit smoothie in the UK market). Therefore, we suggest future research replicate the generalizability of our findings by testing different products in the same market (e. g., water bottle and fruit smoothie in the UK market) or consider testing the same product across different markets. Third, we concentrated on a western sample. However, it could be that a company size signal creates different meanings for consumers who have different cultural backgrounds as cultural differences are noted to have an impact on consumer behavior (Kim et al., 2002; Belk et al., 2005). Fourth, even though these experimental studies are strong in internal validity, they capture behavioral intentions expressed as a willingness to buy a product. Future research should consider measuring real behavior in a controlled lab setting or even in the field. Finally, it would be interesting to assess what happens if a small company shows irresponsible behavior. Previous research has demonstrated that when small companies do not behave in line with consumer expectations and show non-communal behavior, consumers show decreased company evaluations (Yang & Aggarwal, 2019). However, it is interesting whether the same effect would hold for consumers with low social responsibility or they would show an increased willingness to buy from such a small company as it presumably aligns with their own internal values.

References

Aaker, D. A., & Keller, K. L. (1990). Consumer Evaluations of Brand Extensions. Journal of Marketing, 54, 27–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252171

Aras, G., Aybars, A., & Kutlu, O. (2010). Managing corporate performance: Investigating the relationship between corporate social responsibility and financial performance in emerging markets. International Journal of Productivity and Performa nce Management, 59(3), 229–254. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410401011023573

Bartsch, F., Riefler, P., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2016). A Taxonomy and Review of Positive Consumer Dispositions toward Foreign Countries and Globalization. Journal of International Marketing, 24(1), 82–110. https://doi.org/10.1509/jim.15.0021

Baumann-Pauly, D., Wickert, C., Spence, L. J., & Scherer, A. G. (2013). Organizing Corporate Social Responsibility in Small and Large Firms: Size Matters. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(4), 693–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1827-7

Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.01.001

Belk, R., Devinney, T., & Eckhardt, G. (2005). Consumer Ethics Across Cultures. Consumption Markets & Culture, 8(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253860500160411

Bhattacharya, C., & Sen, S. (2004). Doing Better at Doing Good: When, Why, and How Consumers Respond to Corporate Social Initiatives. California Management Review, 47(1), 9–24. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166284

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The Company and the Product: Corporate Associations and Consumer Product Responses. Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252190

Boulding, W., & Kirmani, A. (1993). A Consumer-Side Experimental Examination of Signaling Theory: Do Consumers Perceive Warranties as Signals of Quality?. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 111–123.

Caruana, R., & Chatzidakis, A. (2014). Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR): Toward a Multi-Level, Multi-Agent Conceptualization of the “Other CSR”. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(4), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1739-6

Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2011). Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67.

Dartey-Baah, K., & Amoako, G. K. (2021). A review of empirical research on corporate social responsibility in emerging economies. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 16(7), 1330–1347. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-12-2019-1062

Davis, K. (1973). The Case for and Against Business Assumption of Social Responsibilities. Academy of Management Journal, 16, 312–323.

Davvetas, V., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2016). How Product Category Shapes Preferences Toward Global and Local Brands: A Schema Theory Perspective. Journal of International Marketing, 24(4), 61–81. https://doi.org/10.1509/jim.15.0110

Devinney, T. M., Auger, P., Eckhardt, G., & Birtchnell, T. (2006). The Other CSR: Consumer Social Responsibility. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Leeds University Business School Working Paper No. 15-04, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.901863

De Vries, E. L., & Duque, L. C. (2018). Small but Sincere: How Firm Size and Gratitude Determine the Effectiveness of Cause Marketing Campaigns. Journal of Retailing, 94(4), 352–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2018.08.002

Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., & Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of Price, Brand, and Store Information on Buyers’ Product Evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(3), 307–319. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3172866

Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (1993). Stereotypes and evaluative intergroup bias. In D. M. Mackie & D. L. Hamilton (Eds.), Affect, Cognition and Stereotyping: Interactive processes in group perception (pp. 167–193). Academic Press.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2010). Maximizing Business Returns to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of CSR Communication. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12, 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00276.x

Durif, F., Boivin, C., Rajaobelina, L., & François-Lecompte, A. (2011). Socially Responsible Consumers: Profile and Implications for Marketing Strategy. International Review of Business Research Papers, 7(6), 215–224.

European Commission. (2011). Corporate Social Responsibility: A new definition, a new agenda for action. MEMO/11/730.

Erdem, T., & Swait, J. (1998). Brand Equity as a Signaling Phenomenon. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 7(2), 131–157.

Erdem, T., & Swait, J. (2004). Brand Credibility, Brand Consideration, and Choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 191–198.

Field, A. (2021, December) Socially Responsible Consumer Spending At A Record High. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/annefield/2021/12/19/socially-responsible-consumer-spending-at-a-record-high/?sh=5027903a4eb6

Freund, A., Flynn, F., & O’Connor, K. (2023). Big Is Bad: Stereotypes About Organizational Size, Profit-Seeking, and Corporate Ethicality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672231151791

Grant, D. S. I., Bergesen, A. J., & Jones, A. W. (2002). Organizational Size and Pollution: The Case of the U.S. Chemical Industry. American Sociological Review, 67(3), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088963

Grappi, S., Romani, S., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2013). Consumer response to corporate irresponsible behavior: Moral emotions and virtues. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1814–1821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.002

Green, T., & Peloza, J. (2014). How do consumers infer corporate social responsibility? The role of organisation size. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 13(4), 282–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1466

Hall, R. H., Johnson, N. J., & Haas, J. E. (1967). Organizational Size, Complexity, and Formalization. American Sociological Review, 32(6), 903–912. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092844

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). Guilford publications.

Jamali, D., Zanhour, M., & Keshishian, T. (2009). Peculiar Strengths and Relational Attributes of SMEs in the Context of CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(3), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9925-7

Jung, H., Bae, J., & Kim, H. (2022). The effect of corporate social responsibility and corporate social irresponsibility: Why company size matters based on consumers’ need for self-expression. Journal of Business Research, 146, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.03.024

Kim, J. O., Forsythe, S., Gu, Q., & Moon, S. J. (2002). Cross‐cultural consumer values, needs and purchase behavior. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19(6), 481–502. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760210444869

Kimberly, J. R. (1976). Organizational Size and the Structuralist Perspective: A Review, Critique, and Proposal. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21, 571–597.

Lee, K., & Shin, D. (2010). Consumers’ responses to CSR activities: The linkage between increased awareness and purchase intention. Public Relations Review, 36(2), 193–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.10.014

Liu, H., Schoefer, K., Fastoso, F., & Tzemou, E. (2021). Perceived Brand Globalness/Localness: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Directions for Further Research. Journal of International Marketing, 29(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069031X209731

Miller, N. J. (2001). Contributions of social capital theory in predicting rural community in shopping behavior. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 30(6), 475–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(01)00122-6

Mishina, Y., Dykes, B., Block, E., & Pollock, T. (2010). Why “Good” Firms do Bad Things: The Effects of High Aspirations, High Expectations, and Prominence on the Incidence of Corporate Illegality. Academy of Management Journal, 53(4), 701–722. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.52814578

Mohr, L. A., Webb, D. J., & Harris, K. E. (2001). Do Consumers Expect Companies to be Socially Responsible? The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Buying Behavior. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 35(1), 45–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2001.tb00102.x

Mohr, L. A., & Webb, D. J. (2005). The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39(1), 121–147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2005.00006.x

Murray, K. B., & Vogel, C. M. (1997). Using a hierarchy-of-effects approach to gauge the effectiveness of corporate social responsibility to generate goodwill toward the firm: Financial versus nonfinancial impacts. Journal of Business Research, 38(2), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(96)00061-6

Newman, G. E., & Bloom, P. (2012). Art and authenticity: The importance of originals in judgments of value. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(3), 558–569. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026035

Öberseder, M., Schlegelmilch, B. B., & Gruber, V. (2011). “Why Don’t Consumers Care About CSR?”: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Role of CSR in Consumption Decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(4), 449–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0925-7

Ovide, S. (2020, October 23). Why Washington Hates Big Tech. The New York Times.

Özsomer, A. (2012). The Interplay between Global and Local Brands: A Closer Look at Perceived Brand Globalness and Local Iconness. Journal of International Marketing, 20(2), 72–95.

Paharia, N., Avery, J., & Keinan A., (2014). Positioning Brands against Large Competitors to Increase Sales. Journal of Marketing Research, 51(6), 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.13.0438

Paharia, N., Keinan, A., Avery, J. & Schor, J. (2011). The Underdog Effect: The Marketing of Disadvantage and Determination through Brand Biography. Journal of Consumer Research,37(5), 775–790. https://doi.org/10.1086/656219

Pomering, A., & Dolnicar, S. (2009). Assessing the Prerequisite of Successful CSR Implementation: Are Consumers Aware of CSR Initiatives?. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 285–301.

Quazi, A., Amran, A., & Nejati, M. (2016). Conceptualizing and measuring consumer social responsibility: A neglected aspect of consumer research. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12211

Rahman, F., & Norman, R. T. (2016). The effect of firm scale and CSR geographical scope of impact on consumers’ response. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 28, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.10.006

Rauschendorfer, N., Prügl, R., & Lude, M. (2022). Love is in the air. Consumers’ perception of products from firms signaling their family nature. Psychology & Marketing, 39, 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21592

Remmé, J. H. M. (2015). Corporate Social Responsibility in the Netherlands. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance. In S. O. Idowu, R. Schmidpeter & M. S. Fifka (Eds.), Corporate Social Responsibility in Europe (Edition 127, pp. 93–123). Springer. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-13566-3_6

Roberts, J. A. (1993). Sex Differences in Socially Responsible Consumers’ Behavior. Psychological Reports, 73(1), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1993.73.1.139

Schlaile, M. P., Klein, K., & Böck, W. (2018). From Bounded Morality to Consumer Social Responsibility: A Transdisciplinary Approach to Socially Responsible Consumption and its Obstacles. Journal of Business Ethics, 149(3), 561–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3096-8

Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does Doing Good Always Lead to Doing Better? Consumer Reactions to Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.2.225.18838

Smith, E. A., & Bliege Bird, R. (2005). Costly Signaling and Cooperative Behavior. In H. Gintis, S.Bowles, R.Boyd & E.Fehr (Eds.), Moral Sentiments and Material Interests: The Foundations of Cooperation in Economic Life (pp. 115–148).

Spence, L. J. (1999). Does size matter? The state of the art in small business ethics. Business Ethics, the Environment and Responsibility, 8(3), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8608.00144

Spence, L. J. (2004). Small firm accountability and integrity. In G. Brenkert (Ed.), Corporate Integrity and Accountability (pp. 115–128). London: Sage.

Spence, L. J. (2007). CSR and Small Business in a European Policy Context: The Five “C” s of CSR and Small Business Research Agenda 2007. Business and Society Review, 112(4), 533–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8594.2007.00308.x

Spence, M. (1973). Job Market Signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374.

Spence, M. (2002). Signaling in Retrospect and the Informational Structure of Markets. American Economic Review, 92, 434–459.

Stankovic, K. (2019, September) Do Consumers Actually Care about Corporate Social Responsibility? GWI. https://blog.gwi.com/chart-of-the-week/corporate-social-responsibility/

Steenkamp, J. B. (2014). How global brands create firm value: The 4V model. International Marketing Review, 31(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-10-2013-0233

Strizhakova, Y., Coulter, R. A., & Price, L. L. (2008). The Meanings of Branded Products: A Cross-National Scale Development and Meaning Assessment. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 25(2), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2008.01.001

Sweetin, V. H., Knowles, L. L., Summey, J. H., & McQueen, K. S. (2013). Willingness-to-punish the corporate brand for corporate social irresponsibility. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1822–1830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.003

Taylor, V. A., & Bearden, W. O. (2002). The Effects of Price on Brand Extension Evaluations: The Moderating Role of Extension Similarity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30, 131–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/03079459994380

Thiessen, M. A. (2021, March 4). Democrats demonized Big Pharma. Now it’s saving us from covid-19. The Washington Post.

Thompson, C., & Arsel, Z. (2004). The Starbucks Brandscape and Consumers’ (Anticorporate) Experiences of Glocalization. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(3), 631–642. https://doi.org/10.1086/425098

Uzdavinyte, E., Gineikiene, J., Kaminskiene, Z. (2023 under review). It’s the Smallness that Counts: Consumer Preferences for Small vs. Large Companies Products

Valor, C., Antonetti, P., & Zasuwa, G. (2022). Corporate social irresponsibility and consumer punishment: A systematic review and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 144, 1218–1233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.02.063

Vitell, S. J. (2015). A Case for Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR): Including a Selected Review of Consumer Ethics/Social Responsibility Research. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(4), 767–774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2110-2

Webster Jr, F. E. (1975). Determining the Characteristics of the Socially Conscious Consumer. Journal of Consumer Research, 2(3), 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1086/208631

White, T. B., & Yuan, H. (2012). Building trust to increase purchase intentions: The signaling impact of low pricing policies. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(3), 384–394.

Wright, P. (1986). Presidential Address Schemer Schema: Consumers’ Intuitive Theories about Marketers’ Influence Tactics. Advances in Consumer Research, 13, 1–3.

Yang, L. W., & Aggarwal, P. (2019). No Small Matter: How Company Size Affects Consumer Expectations and Evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(6), 1369–1384. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy042

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52 (July), 2–22.

Zhang, Y., & Wiersema, M. F. (2009). Stock Market Reaction to CEO Certification: The Signaling Role of CEO Background. Strategic Management Journal, 30(7), 693–710. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.772

Zhou, L., Teng, L., & Poon, P. S. (2008). Susceptibility to global consumer culture: A three‐dimensional scale. Psychology & Marketing, 25(4), 336–351. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20212

Appendix A

Scenarios of Experiments

Scenario for Experiment 1

Small company condition

Large company condition

Medium company condition

Scenario for Experiment 2

Small company condition

Large company condition

Medium-sized company condition

Control condition

Appendix B

Measurement of Constructs

|

|

Experiment |

Experiment |

|

Willingness to Buy (adapted from Dodds, Monroe, & Grewal, 1991) |

||

|

The likelihood that I will purchase this water bottle is: (1-very low, 7-very high). |

α = 0.92 M = 3.20 SD = 1.44 |

N/A |

|

If I were going to buy a water bottle, I would consider buying this one (1-strongly disagree, 7-strongly agree). |

||

|

The probability that I would consider buying this water bottle is: (1-very low, 7-very high). |

||

|

My willingness to buy this water bottle is: (1 very low, 7 very high). |

||

|

I would recommend this water bottle to other people in the future (1-strongly disagree, 7-strongly agree). |

||

|

Willingness to buy (adapted from Aaker & Keller, 1990; Taylor & Bearden, 2002) |

||

|

I have the intention of buying this smoothie. |

N/A |

α = 0.93 M = 4.38 SD = 1.35 |

|

I would recommend this smoothie to other people in the future. |

||

|

I prefer buying this smoothie. |

||

|

Consumer social responsibility (self-developed scale) |

||

|

In my opinion, I am a socially responsible person. |

N/A |

α = 0.81 M = 5.07 SD = 1.06 |

|

I am very concerned about the well-being of society. |

||

|

I follow high ethical standards. |

||

Note. N/A – not assessed