Lietuvos chirurgija ISSN 1392–0995 eISSN 1648–9942

2024, vol. 23(3), pp. 181–197 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/LietChirur.2024.23(3).5

Amyand’s Hernia in Adults – an Analysis of Recent Literature

Sajad Ahmad Salati

Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, Qassim University, Saudi Arabia

E-mail: s.salati@qu.edu.sa

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2998-7542

https://ror.org/01wsfe280

Lamees Sulaiman AlSulaim

Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, Qassim University, Saudi Arabia

E-mail: dr.lameesz@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5785-8468

https://ror.org/01wsfe280

Mohammad Ahmed Elmuttalut

Department of Community Medicine, Al-Rayan National College of Medicine, Al-Madinah Al-Munawarah, Saudi Arabia

E-mail: motallat@gamil.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0677-6390

Abstract. Amyand’s hernia is a rare disorder characterized by the presence of the vermiform appendix within an inguinal hernia. It is predominantly found in the pediatric age group, and its occurrence in adulthood is rare. Hence, a systematic analysis of twenty-six case reports of Amyand’s hernia published in the peer-reviewed literature in the year 2023 is presented with emphasis on variables including age of the patient, gender, clinical presentation, side of the inguinal hernia, imaging modalities used for evaluation, achievement of preoperative diagnosis or otherwise, classification, appendix management, hernia management, surgical approach, and outcomes.

Keywords: Amyand’s hernia, vermiform appendix, inguinal hernia, appendicitis, abscess, perforation, mesh, hernia repair.

Received: 2024 05 20. Accepted: 2024 07 05.

Copyright © 2024 Sajad Ahmad Salati, Lamees Sulaiman AlSulaim, Mohammad Ahmed Elmuttalut. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Abdominal hernia is defined as a protrusion of the viscera through an anatomical opening. All intraabdominal organs, except for the pancreas, can potentially herniate. Herniation of the vermiform appendix occurs rarely, and an inguinal hernia containing the appendix is termed an Amyand’s hernia (AH), after the name of Claudius Amyand, who, in 1735, reported the first inguinal hernia containing an inflamed perforated appendix with faecal fistula in an 11-year-old boy [1]. It was in 1953 that the eponym Amyand Hernia was coined by Creese and further used by Hiatt and Hutchinson to give due credit to Amyand for being the first surgeon to have operated on this rare type of condition [1, 2].

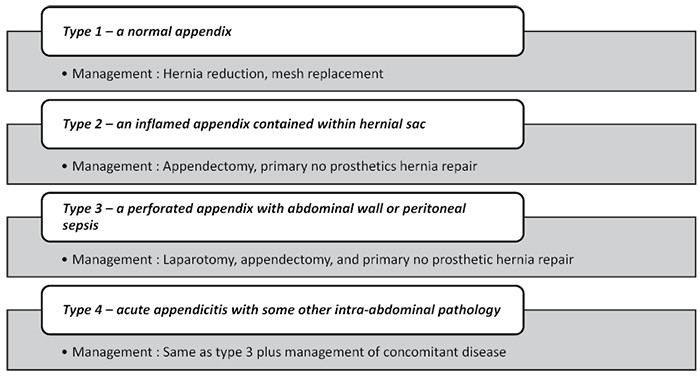

About 20 million inguinal hernia repair operations are conducted annually worldwide, and the incidence of AH is approximately 0.19% to 1.7% [3]. AH containing an inflamed or perforated appendix have an estimated incidence of 0.07–0.13% [4]. AH is mostly located on the right side, and cases have been recorded in every age group, but as a result of the patency of the processus vaginalis in the pediatric population, it is about three times more common in children, frequently affecting males. In adults, this condition is rare and tends to present a diagnostic challenge due to its rarity, indistinct clinical presentation, and ambiguous appearance on imaging [5]. Losanoff and Basson [6] proposed in 2007 a classification scheme to determine the management of AH (Figure 1), and in the article, this classification has been used due to its simplicity of application.

Figure 1. Losanoff and Basson classification of Amyand’s hernia

This context led to the compilation of this review in order to gather information on the latest research on the subject of AH in the adult population.

Materials and methods

Methods. A literature search was conducted systematically through electronic databases, including PubMed, ResearchGate, Google Scholar, and Scopus, using the key words “Amyand hernia; appendix; inguinal hernia”. The search was carried out by using individual keywords with a combination of Boolean logic (AND). The study was limited to the literature published in 2023.

Criteria for Considering Articles

Study design. The articles from the peer-reviewed literature were included in the study if they provided an account of the selected variables.

Participants. Male patients of both genders above 18 years of age, diagnosed with Amyand hernia.

Language. English.

Type of article. Case series and case reports.

Participants. Only the patients with a confirmed diagnosis of an AH were included.

Exclusion. All the articles, including editorials, original studies, conference letters, and systematic reviews, that were deficient in information related to the variables of interest were excluded. Similarly, articles in languages other than English were excluded.

Risk of Bias / Limitations. The Saudi Digital Library’s subscription journals, ResearchGate, or Open Access, were the sources of the featured publications. Therefore, it’s possible that some articles may have been overlooked if they weren’t available through these sites.

Methodological Quality Checking. This review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Version 2020 guidelines. Furthermore, the previously published literature reviews were considered for comparison with this study.

Data Synthesis (Extraction and Analysis). The reference lists of articles were investigated manually, and data related to the eleven variables was extracted and arranged in Table 1. The variables included age of the patient, gender, clinical presentation, side of the inguinal hernia (right or left), imaging modalities used for evaluation, achievement of a preoperative diagnosis or otherwise, classification, appendix management, hernia management, surgical approach (laparoscopic or open), and outcome. The collected data were then analyzed with the aid of Microsoft Excel (Office Version 2019). The characteristics of the included cases were described with descriptive statistical analyses, and the information was presented using measures of frequency, dispersion (range, standard deviation), and central tendency (mean), as shown in the results. Any disagreements were settled by the authors’ consensus, and they adhered to the PRISMA statement’s principles.

Table 1. Patient characteristics in the included articles

|

Serial No. |

Series |

Age (years) |

Gender (M/F) |

Clinical features |

Imaging |

Preoperatively diagnosed |

Losanoff and Bassof |

Appendix management |

Hernia Management |

Surgical Approach |

Outcome |

Other relevant remarks |

|

1. |

Litchinko et al. [7] |

56 |

M |

Acute right scrotal pain and fever – 3 days O/E a giant type 3 right inguinoscrotal hernia extending below the superior border of the patellar bone. Notably, there was erythema and tenderness localized below the right side of the scrotum. |

CT scan: perforated appendicitis located in the inferior part of the scrotum. |

Y |

3 |

Appendectomy |

Mesh-free Shouldice repair |

OL |

Uneventful postoperative phase; |

Before the onset of acute presenting symptoms, patient had progressive right inguinoscrotal hernia (giant) for approximately 15 years with intermittent discomfort. |

|

2. |

Bawa |

65 |

M |

Intermittent pain and swelling in right groin since months |

None. |

N |

1 |

Reduction |

Tension-free hernioplasty with mesh |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase; no hernia recurrence at 2 weeks. |

High risk cardiac disorder, hence operated under local anaesthesia. |

|

3. |

Banouei & |

83 |

M |

Right Inguinoscrotal swelling of 10 years with recent increase in size O/E irreducible, tender inguinoscrotal hernia with erythema of overlying skin. |

USG: 12 mm defect in the floor of inguinal canal with fatty tissue herniation. Appendix not seen. |

N |

2 |

Appendectomy |

Mesh-free repair |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase; no hernia recurrence at 2 weeks. |

Operated under spinal anaesthesia; inflamed appendix was 23 cm long, adhered to spermatic cord. |

|

4. |

Riojas-Garza et al. [10] |

57 |

M |

10-day history of generalized weakness, anorexia, myalgias, lethargy, breathlessness, right lumbar and diffuse abdominal pain which had increased in the last 2 days. O/E tender lower abdomen; tender, indurated, right inguinoscrotal hernia. |

CT scan: a giant inflamed sigmoid diverticulum (10.4 cm) and an Amyand hernia with a complicated appendicitis. |

Y |

4 |

Appendectomy |

Mesh-free Desarda repair |

OLI |

Postoperative respiratory failure requiring ICU care; sepsis, multiorgan failure and death after 1 month. |

Hartman’s procedure was also accomplished as sigmoid diverticulum had multiple ischemic patches. |

|

5. |

Siddiqui et al. [11] |

60 |

M |

Recent onset right inguinoscrotal swelling O/E right, irreducible hernia with positive cough impulse. |

None. |

N |

1 |

Reduction |

Hernioplasty with polypropylene mesh |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

8 cm long appendix. |

|

6. |

Zhimomi et al. [12] |

64 |

M |

Painful right inguinal swelling for 15 days and foul-smelling discharge for 2 days. O/E a tender, erythematous swelling over the right inguinal region extending up to the base of the right hemiscrotum. There was a 3×3 cm ulcer over the right mid inguinal point with a necrotic and purulent ulcer floor. |

USG: dilated bowel loop and omentum in the right inguinoscrotal region with reduced vascularity and absent peristalsis suggestive of a right inguinal hernia with partial strangulation. |

N |

3 |

Appendectomy |

Mesh-free hernia repair |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

The hernia sac contained a perforated inflamed appendix with a 5×3 mm fecalith. |

|

7. |

Nadzrin [13] |

84 |

M |

Painful right inguinal swelling, constipation and abdominal distension for 3 days. O/E irreducible, tender, right inguinal hernia with no skin changes. |

X-ray abdomen: non-specific small and large intestinal dilatation. |

N |

3 |

Appendectomy |

Mesh-free Bassini hernia repair |

OLI |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

Appendix was perforated at the base and could not be retrieved through groin incision and hence required laparotomy and lavage. |

|

8. |

Radboy et al. |

48 |

M |

Right groin lump for two months and pain in right lower quadrant and groin for 2 days. O/E tenderness in right lower quadrant. |

Abdominopelvic ultrasound: 9 mm appendix in the right inguinal canal. |

Y |

2 |

Appendectomy |

No repair |

L |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

Hernioplasty with mesh was postponed for later date. |

|

9. |

Alyahyawi [15] |

81 |

M |

Pain for 4 days in a longstanding left groin lump. O/E irreducible left inguinoscrotal hernia, with erythema over the overlying skin. |

USG: a left inguinal hernia with a thickened hernia sac with intestinal content. |

N |

1 |

Reduction |

Lichtenstein tension-free mesh repair |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

The intraoperative examination revealed a large, approximately 30 cm by 15 cm left-sided hernia containing a loop of the terminal ileum, cecum, and appendix. |

|

10. |

Craciun [16] |

77 |

M |

Pain for 4 days in right inguinal lump of 3 years O/E irreducible, non-tender, right inguinal hernia (15x10 cm) with erythema of overlying skin. |

None. |

N |

3 |

Right hemicolectomy (+ right orchidectomy) |

Mesh-free hernia repair |

OLI |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

Opened hernia sac revealed a phlegmonous, and dilated appendix with peri-appendicular purulent content and fibrin deposits, dislocated from the caecum. The terminal ileum loop and ascending colon and right testis were encompassed in the septic process. |

|

11. |

Jakovljevic et al. [17] |

84 |

M |

Pain for 2 days in right inguinal lump of 3 months O/E irreducible, non-tender, right inguinal hernia. |

None. |

N |

2 |

Appendectomy |

Modified Bassini |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

– |

|

12 |

Jha et al. [18] |

66 |

M |

Pain for one day in longstanding left inguinal swelling and pain abdomen with vomiting for 3 hours. O/E large irreducible left inguinoscrotal hernia. |

Abdominal X-ray: gas under the diaphragm. Scrotal USG: obstructed left inguinoscrotal hernia with dilated and aperistaltic bowel loop with minimum vascularity. |

N |

4 |

Appendectomy + primary closure of caecal perforation + temporary diversion ileostomy |

Mesh-free hernia repair |

OL |

Uneventful postoperative phase; ileostomy closed at 6 months. |

Appendix, omentum, and caecum were found inside her- |

|

13. |

Shah [19] |

70 |

M |

Acute abdominal pain of few hours. O/E right, irreducible, inguinal hernia. |

None. |

N |

1 |

Appendectomy |

Robotic right inguinal hernia repair with mesh |

R |

Uneventful postoperative phase except for short-term groin pain requiring analgesics |

– |

|

14. |

Das et al. |

60 |

M |

Right inguinal pain and swelling for 3 days; constipation and vomiting 1 day. O/E a distended abdomen with no tenderness; bowel sounds were exaggerated; right, 6x6 cm irreducible, inguinoscrotal hernia with tenderness and erythematous overlying skin. |

Abdominal X-ray: multiple air-fluid levels suggesting small bowelobstruction. USG abdomen: free echogenic fluid in the pelvis with multiple dilated small bowel loops more than 3.8 cm in diameter. USG inguinoscrotal region: a right incarcerated indirect hernia sac with a non-peristaltic, blind-ending tubular structure with fluid collection noted as content. |

N |

3 |

Appendectomy |

Mesh-free Bassini hernia repair |

OLI |

Surgical site infection managed conservatively. |

On exploration, there was a right inguinal hernia sac with thick walls and dense adhesions, separate from the spermatic cord, and testis. The hernia sac, contained 300 ml of pus and a 4 cm impacted fishbone perforating the wall of 10 cm long inflamed oedematous appendix. |

|

15. |

Sun et al. |

57 |

M |

Acute pain in long standing right inguinoscrotal lump. |

None. |

N |

2 |

Appendectomy |

Partially absorbable (ultrapro) mesh reinforced herniorrhaphy |

OI |

Acute renal failure requiring ICU care in immediate postoperative phase. |

The inguinoscrotal hernia extended below the midpoint of his inner thigh. |

|

16. |

Raj et al. |

57 |

M |

Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting for 1 day. On examination, peritonism but no groin lump nor cough impulse. O/E mildly distended abdomen with generalised guarding and signs of generalised Peritonism and reduced bowel sounds. No palpable groin swelling or cough impulse was evident. |

Abdominal X-ray: unremarkable. CT scan: thick-walled appendix (diameter 1.5 cm), with wall irregularity with the tip entering the right inguinal canal, and associated with significant periappendiceal fat stranding and minimal free fluid in the pelvis. |

Y |

3 |

Appendectomy |

No repair |

L |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

Hernia only identified radiologically and clinical not present on postoperative follow-up. Hence repair not undertaken. |

|

17. |

Corvatta et al. [23] |

72 |

F |

Abdominal pain & nausea for 1 day. O/E distended, tender abdomen with tender irreducible left groin lump. |

USG: protrusion of a hollow viscus through a 42 mm fascial continuum. |

N |

1 |

Reduction |

Hernioplasty with mesh |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase with no recurrence at 1 year. |

A synchronous ipsilateral femoral hernia was found on exploration and repaired. |

|

18. |

Heo |

65 |

M |

Intermittent pain in right groin for 1 year. O/E slight non-tender bulge in the right groin. Scars from the previous hernia surgery in the left groin and lower midline, with protrusion on standing (not supine). |

CT scan: a right inguinal hernia containing appendix & left recurrent inguinal hernia with omental fat. |

Y |

1 |

Reduction |

Hernioplasty with mesh |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase with no recurrence at 16 months. |

Left recurrent inguinal hernia was repaired with mesh in the same siting. |

|

19. |

Drogge et al. |

71 |

M |

Severe pain for 3 days in long standing right inguinal hernia. O/E right, irreducible indirect, inguinal hernia with warm surface. |

None. |

N |

2 |

Appendectomy |

Shouldice hernia repair (without mesh) |

OI |

Vacuum Assisted Closure (VAC) was applied; otherwise, uneventful postoperative phase. |

Wound was not closed primarily and VAC dressings was applied for 38 days when secondary closure was undertaken. No recurrence at 3 months. |

|

20. |

Ijah et al. |

25 |

M |

Right groin swelling of 3 years with recent pain. O/E reducible, right indirect inguinoscrotal hernia. |

None. |

N |

2 |

Appendectomy |

Hernia repair without mesh |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

Thick 21 cm long pinkish-grey appendix with prominent serosal vessels, visible caecum in hernia sac. |

|

21. |

Bedaiwi et al. [27] |

72 |

M |

Pain for 2 days in progressively growing scrotal lump (present for 4 months) O/E scars over both groins from previous hernia repair. Tenderness in right lower abdomen and swollen right hemi-scrotum. Cough impulse positive over right groin. |

CT scan: a large (wide neck 7 cm) right inguinal hernia causing mass effect on the urethra, intra-hernia appendix with radiological signs of acute inflamed appendix. |

Y |

2 |

Appendectomy |

Hernia repair with Vypro semi-absorbable mesh |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

– |

|

22. |

Krosser |

33 |

M |

Lower abdomen pain for 4 days and constipation for 2 days. O/E tender, right, indirect, inguinal hernia and tender lower abdomen. |

CT scan: ischemic 12 cm x 12 cm omentum and a right-sided inguinal hernia containing the appendix. |

Y |

4 |

Appendectomy |

No repair |

L |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

Amyand’s hernia and ischemic omentum due to omental torsion occurred simultaneously as separate pathologies and as it was not possible to attribute symptoms to either, hence laparoscopic procedure undertaken. |

|

23. |

Teimouri & Karkeabadi |

45 |

M |

Lower abdominal pain and vomiting for few hours. O/E bulge over right inguinal area with tender lower abdomen. |

USG: revealed an inguinal hernia sac containing inflamed fat, anechoic fluid collection and a distended and inflamed donut shape loop measuring 10.5 mm, suggestive of appendicitis. |

Y |

2 |

Appendectomy |

Bassini repair (without mesh) |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

– |

|

24. |

F. Khurshid et al. [30] |

65 |

M |

Pain for 2 days in right inguinal lump that had appeared 2 months ago O/E there was a right, reducible, indirect inguinal region. |

None. |

N |

2 |

Appendectomy |

Hernia repair with mesh |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

– |

|

25. |

Alvi |

70 |

M |

Pain abdomen with inability to pass stool and flatus history for 12 hours O/E bilateral tender irreducible, direct inguinal hernias with scar of previous surgery in left inguinal region. |

X-ray abdomen: dilated small bowel loops suggestive of bowel obstruction. |

N |

1 |

Reduction |

Bassini repair (without mesh) |

OI |

Patient developed respiratory failure and was kept on ventilator. Patient expired on postoperative day 12. |

Left inguinal hernia sac contained appendix and right hernial sac had gangrenous gut segment which required resection. Patient was a known case of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. |

|

26. |

Hatampour et al. |

65 |

M |

Right inguinal swelling and pain for 1 week. O/E right, reducible, indirect inguinal hernia. |

USG: a reducible inguinal hernia with a 1.5 cm defect that included bowel loops. |

N |

1 |

Reduction |

Hernia repair with mesh (Lichtenstein) |

OI |

Uneventful postoperative phase. |

– |

O/E – On examination; Y – Yes; N – No; CT – Computed tomography; USG – Ultrasonogram; OI – Open-inguinal; OL – Open-laparotomy; OLI – Open-laparotomy and inguinal.

Results

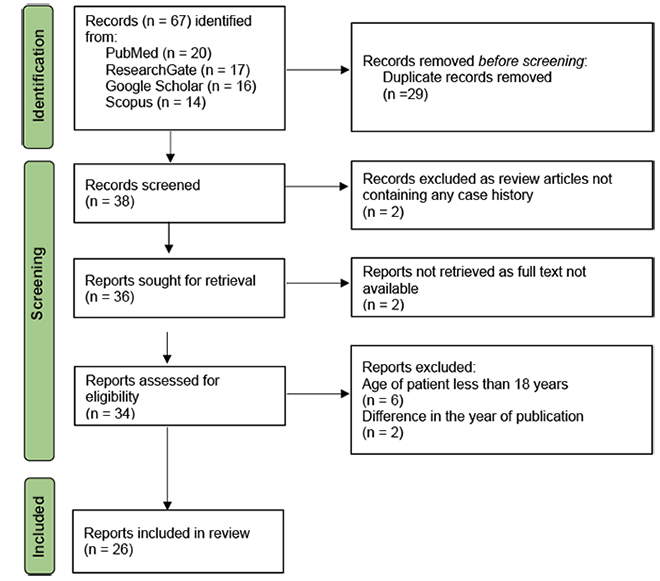

Study Selection. As depicted in Figure 2, the electronic database search resulted in a total of 67 articles. After excluding 29 duplicated articles, titles and abstracts of 38 articles were screened, after which full texts of 36 potentially relevant articles were retrieved for eligibility criteria. Finally, 26 articles were included in the review after detection of an age below 18 years in 6 patients and a difference in the year of publication in 2 case reports.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow chart of the literature search strategies

Study Characteristics. There were 26 cases, ranging in age from 25 to 84 years (mean 62.5 years; SD = 14.159). There were 25 (96.2%) males and 1 (3.8%) female.

Figure 3. Location of hernias

Clinical presentation. Pain in the lower abdomen, groin, and/or scrotum was the commonest chief complaint (n = 25; 96.2%), followed by lumps (n = 24; 92.3%). 10 (38.5%) cases had a preexisting lump (maximum duration 10 years) that turned painful, whereas in 14 (53.8%), the lump and pain appeared acutely within hours or days. Three cases had a history of previous hernia repair on either side.

Location and anatomical type of hernias. 22 (84.6%) hernias were present on the right side and 4 (15.4%) on the left side, as depicted in Figure 3. 25 (96.2%) were indirect inguinal hernias, and 19 (73.1%) were irreducible or incarcerated.

Imaging modalities and achievement of preoperative diagnosis. In 10 (38.7%) cases, no preoperative imaging was undertaken, whereas abdominal/scrotal USG was done in 8 (30.8%), an abdominal CT scan was done in 6 (23.8%), and an abdominal X-ray was done in 5 (19.2%) cases. However, Amyand hernia was diagnosed preoperatively only in 8 (30.8%), with 5 (19.2%) cases being diagnosed on CT scan and 2 (7.7%) on USG. The sensitivity of the CT scan and USG abdomen to pick up Amy and hernia was hence 83.3% and 25%, respectively.

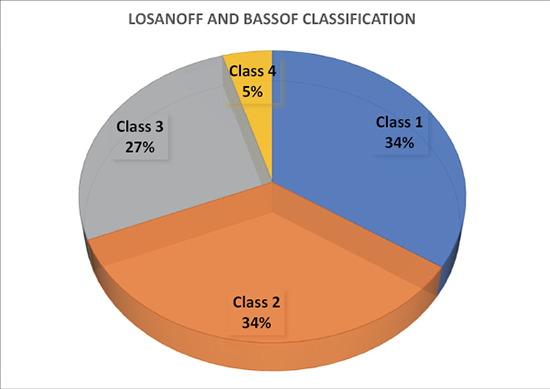

Losanoff and Bassof classification. 8 (30.7%) hernias belonged to Class 1, 9 (34.6%) to Class 2, 6 (23.1%) to Class 3, and 3 (11.5%) to Class 4, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Incidence of Amyand’s hernias as per the Losanoff and Bassof classification

Management. A surgical operation was undertaken in all (100%) cases. The surgical approach was open inguinal in 16 (61.5%), open inguinal plus laparotomy in 4 (15.4%), laparoscopic in 3 (15.4%), laparotomy in 2 (3.8%), and robotic in 1 (3.8%). In Class 1, the vermiform appendix was reduced into the peritoneal cavity along with other hernial contents in 7 out of 8 (87.5%), and an appendectomy was conducted in 1 (12.5%) case. Hernia was repaired by hernioplasty with mesh in 7 (87.5%) cases, and Bassini repair without mesh was undertaken in 1 (12.5%) case.

In Class 2, appendectomy was conducted in all nine (100%) cases. For hernia, herniorrhaphy without mesh was undertaken in 5 (55.6%), hernioplasty with partially absorbable (Ultrapro, Vypro) mesh in 2 (22.2%), and polypropylene mesh in 1 (11.1%). In 1 (11.1%) case, elective hernioplasty with mesh was planned at a later date. In Class 3, appendectomy was conducted in 5 (83.3%) patients, and 1 (16.7%) patient required right hemicolectomy with orchidectomy. Hernia was managed by mesh-free herniorrhaphy in 5 (83.3%) cases, and no repair was undertaken in 1 (16.7%) case. In Class 4, appendectomy was conducted in all three (100%). To manage the additional abdominal pathology, 1 (33.3%) patient each required primary closure of caecal perforation with a temporary diversion ileostomy, Hartman’s procedure to handle sigmoid diverticulum with multiple ischemic patches, and excision of the ischemic omentum, respectively. Hernia was repaired without mesh in 2 (66.7%) patients, and no repair was undertaken in 1 (33.3%) patient.

Outcomes. 22 (84.6%) cases had an uneventful postoperative phase and recovered. 1 (3.8%) case had acute renal failure requiring intensive care, and 1 (3.8%) case had a surgical site infection. 2 (7.7%) cases developed postoperative respiratory failure, sepsis, and multiorgan failure and died.

Discussion

Amyand hernia (AH) is a rare disorder, and a literature search could identify only 28 adult patients in the year 2023. The mean age of 62.5 years and the fact that 10 cases (38.5%) were 70 years and older implies that no age group is immune. Delayed diagnosis can even prove fatal, as in this analysis, 2 (7.7%) patients succumbed to the complications. The pathophysiology of AH is not clear, and many theories have been postulated in the literature to explain the occurrence of AH. There may be a role played by the coexistence of a patent process vaginalis and a fibrous connection between the appendix and testis [33]. A long appendix, loose peritoneal reflections over the colon, and a redundant cecum may potentially cause the appendix to reach into and get retained in the inguinal hernia sac [34]. Similarly, the precise mechanism of appendicitis within an inguinal hernia sac is also not fully understood. It is suggested that the muscle contractions and episodic rise in intraabdominal pressure during acts like defecation, coughing, etc. may compress the appendix in the external inguinal ring, thereby compromising its vascularity and resulting in bacterial overgrowth and inflammation. Narrowing of the neck of the hernia may also play a role by causing extraluminal obstruction [35].

AH behaves differently, as unlike usual inguinal hernia with bowel content, it may not manifest with features of bowel obstruction, and there is a range of complications that can potentially occur, including perforation with localized abscess, or peritonitis, abdominal wall necrotizing fasciitis, epididymo-orchitis, or testicular vascular thrombosis. In this analysis, 5 (19.2%) had perforated appendices, and one of the cases required right hemicolectomy with orchidectomy. AH (Class 4) has an intrabdominal pathology, and in this analysis, there were 3 (11.5%) such cases with associations like sigmoid diverticulum with ischemic patches, caecal perforation, and omental torsion.

In most cases, AH is diagnosed incidentally during a surgical operation, particularly when imaging tools are underutilized and the assessment is made only on the basis of clinical features and blood work. In this analysis, AH was diagnosed preoperatively only in 8 (30.8%) cases. On a retrospective audit of 60 AH cases treated over 12 years, Weber et al. [36] found that preoperative diagnosis had been made in only 1 (1.7%) case. Sharma et al. [4] had treated 18 patients with AH, and none of the patients were diagnosed pre-operatively. However, in our analysis, we found that a CT scan has a sensitivity of 83.3% in the detection of AH, making it a viable tool for diagnosis. On a CT scan, the primary signs deemed pathognomonic for AH include a blind-ending tubular structure arising from the base of the caecum and lying inside the hernia sac. Wall thickening, hyperaemia, and periappendiceal fat stranding indicate appendicitis [37, 38]. In this analysis, the sensitivity of USG in the diagnosis of AH was only 25%, but in the literature, more encouraging results have been published. On analysis of a series of 21 cases of AH, Okur et al. found that a preoperative ultrasound had been performed in 12 cases (57.1%) and a diagnosis had been made in 9/12 (75%) of them. The most significant feature of AH on USG is the presence of a non-compressible tubular structure within the hernia sac.

In this analysis, 22 (85%) hernias were present on the right side and 4 (15%) on the left side, as depicted in Figure 3. The higher frequency on the right side is attributed to the greater incidence of inguinal hernia on the right side. Left-sided AH is ever rare and is considered to be a consequence of the mobile cecum syndrome and lengthy appendix, though theoretically, it can arise in cases of situs inversus or malrotation [33, 39]. Homes et al. [40] reviewed 30 cases of AH, and only 3 (10%) were left-sided.

The management of the analyzed cases was mostly in alignment with the therapeutic scheme of Losanoff and Bassonto (Figure 1). For Class 1 with a healthy appendix, reduction was done in 7 (87.5%), and appendectomy was conducted in 1 (12.5%). Hernia was repaired by hernioplasty with mesh in 7 (87.5%) cases, and Bassini repair without mesh was undertaken in 1 (12.5%) case. Appendectomy for the Class 1 appendix is not recommended as the transection of a fecal-containing organ turns a clean surgery into a clean-contaminated one, thereby increasing the risk of surgical site infection [33]. Furthermore, the retained healthy appendix. Can serve as a reserve for possible future requirements in biliary tract reconstruction, urinary diversion, or appendicostomy [33, 41]. It is recommended in the literature that the appendix be handled with care during reduction, as undue manipulation of a healthy appendix may cause trauma and induce secondary appendicitis [36]. In this analysis, for Class 2 AH, appendectomy was conducted in all nine (100%) cases. For hernia, herniorrhaphy without mesh was undertaken in 5 (55.6%), hernioplasty with partially absorbable mesh in 2 (22.2%), and polypropylene mesh in 1 (11.1%). The Losanoff and Bassonto management scheme does not strongly recommend the use of any prosthetics in hernia repair due to the potentially heightened risk of surgical site infection. But there are other reports in the literature where encouraging results have been derived with the application of mesh with adequate antibiotic coverage [33].

The three patients in this review, where mesh was used after appendectomy for acute appendicitis, did not suffer from any complications. Chatzimavroudis et al. [42] have reported that synthetic mesh can be used with success in cases of inflamed or perforated Amy and hernias without any significant increase in post-operative complications, and that a septic environment is not an absolute contraindication to the use of mesh for hernioplasty. For Class 3 and 4 AH, the cases in this analysis followed the Losanoff and Bassonto management scheme, thereby managing the sepsis and concomitant abdominal pathologies with the avoidance of any mesh or prosthesis in hernia repair. The surgical approach depends on the condition of the patient, the skills of the operating surgeon, and the availability of logistics. In this analysis, the approach was open in 22 (84.6%), laparoscopic in 3 (11.5%), and robotic in 1 (3.8%). The laparoscopic approach offers the advantage of being a minimally invasive diagnostic and therapeutic modality. Vermillion et al. [43] were the first to report laparoscopic reduction of AH, and in recent years, the adoption of this approach has been on the rise [5]. And the discovery of complications may necessitate a conversion from laparoscopic to an open approach, like in other laparoscopic operations. Salemis et al. [44] reported conversion from laparoscopic to midline laparotomy in a case where an indirect inguinal hernia repair revealed a gangrenous perforated appendix with periappendicular abscess within an inguinal hernia.

Conclusions

Amyand’s hernia is a rare entity but healthcare providers should remain vigilant about this potential diagnosis. CT scan is a useful armament to detect this hernia. If discovered during operation, surgeons should adapt their surgical strategies on the basis of recent evidences and aim at prevention of hernia recurrence while effectively minimizing the chances of infection. Though standard therapeutic protocols have not been universally agreed upon, but Losanoff and Basson’s classification scheme serves as a useful guide in management of Amyand’s hernia.

Funding. The Authors declare that they did not receive any grant/funds for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest. The Authors declare that they do not have any relevant financial or non-financial conflicts of interest to report.

Author contributions. All authors committed to assume responsibility for the project and contributed in various degrees to data analysis, article drafting, and critical revision.

Data availability statement. Requests for the data used to support the findings may be sent by email to the corresponding author, who would be glad to provide it to anyone.

Patient Consent. Patient consent is not applicable because no firsthand cases have been presented and the data is obtained from case reports that have already been published by other renowned academics.

Ethics Committee approval. According to the institution’s policy, reviews articles do not need approval from the ethical committee; nonetheless, permission from the departmental research committee has been acquired.

References

1. Bratu D, Mihetiu A, Sandu A, Boicean A, Roman M, Ichim C, Dura H, Hasegan A. Controversies regarding mesh utilisation and the attitude towards the appendix in Amyand’s hernia – a systematic review. Diagnostics 2023; 13(23): 3534.

2. Komorowski AL, Moran Rodriguez J. Amyand’s hernia. Historical perspective and current considerations. Acta Chir Belg 2009; 109(4): 563–564.

3. Shekhani HN, Rohatgi S, Hanna T, Johnson JO. Amyand’s hernia: a case report. J Radiol Case Rep 2016; 10(12): 7–11.

4. Sharma H, Gupta A, Shekhawat NS, Memon B, Memon MA. Amyand’s hernia: a report of 18 consecutive patients over a 15-year period. Hernia 2007; 11(1): 31–35.

5. Ivanschuk G, Cesmebasi A, Sorenson EP, Blaak C, Loukas M, Tubbs SR. Amyand’s hernia: a review. Med Sci Monit 2014; 28(20): 140–146.

6. Losanoff JE, Basson MD. Amyand hernia: what lies beneath – a proposed classification scheme to determine management. Am Surg 2007; 73(12): 1288–1290.

7. Litchinko A, Botti P, Meurette G, Ris F, Dupuis A. A unique case of perforated appendicitis in a giant incarcerated right-sided inguinal hernia: challenges and surgical management. Am J Case Rep 2023; 24: e941649.

8. Bawa A, Kansal R, Sharma S, Rengan V, Sundaram PM. Appendix playing hide and seek: a variation to Amyand’s hernia. Cureus 2023; 15(3): e36326.

9. Banouei F, Komaki M. A rare case of inguinal hernia with complete appendix herniation to the scrotum. Med Case Rep 2023; 9(3): 268.

10. Riojas-Garza A, Hinostroza-Sanchez MA, Gutierrez-Cerda M, Gutierrez-Gandara P, Anguiano-Landa L, Estevez-Cerda SC. Amyand’s hernia in a patient with acute complicated diverticulitis. A case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2023; 112: 108972.

11. Siddiqui A, More R, Kamble A, More S. Management of Amyand’s hernia: a case report. SN Compr Clin Med 2023; 5(1): 237.

12. Zhimomi A, Nandy R, Pradhan D. Amyand’s hernia with a perforated appendix and an enterocutaneous fistula: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2023; 112: 108975.

13. Mohd Nadzrin NA. Perforated Amyand’s hernia. J Surg Surgic Case Rep 2023; 4(2): 1034.

14. Radboy M, Kalantari ME, Einafshar N, Zandbaf T, Bagherzadeh AA, Shari’at Moghani M. Amyand hernia as a rare cause of abdominal pain: a case report and literature review. Clin Case Rep 2023; 11(10): e7929.

15. Alyahyawi K. Left-sided Amyand’s hernia: a rare variant of inguinal hernia. Cureus 2023; 15(9): e45113.

16. Crăciun C, Mocian F, Crăciun R, Nemeş A, Coroş M. Perforated appendiceal mucocele within an Amyand’s hernia: a case report and a brief review of literature. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2023; 118(eCollection):1.

17. Jakovljevic S, Cvetkovic A, Spasic M, Spasic B, Petrovic M, Milosevic B. A rare case of type II Amyand’s hernia. J Pak Med Assoc 2023; 73(7): 1518–1520.

18. Jha S, Kandel A, Baral B, Ghimire P. Perforated caecum in a left-sided Amyand’s hernia: a case report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 2023; 61(260): 387–389.

19. Shah S, Syed S, Bayrakdar K, Elsayed O, Poluru K. A rare case of Amyand’s hernia. Cureus 2023; 15(5): e38641.

20. Das A, Pandurangappa V, Tanwar S, Mohan SK, Naik H. Fishbone-induced appendicular perforation: a rare case report of Amyand’s hernia. Cureus 2023; 15(4): e37313.

21. Sun SL, Chen KL, Gauci C. Appendiceal abscess within a giant Amyand’s hernia: a case report. Cureus 2023; 15(3): e36947.

22. Raj N, Andrews BT, Sood R, Saani I, Conroy M. Amyand’s hernia: a radiological solution of a surgical dilemma. Cureus 2023; 15(1): e33983.

23. Corvatta FA, Palacios Huatuco RM, Bertone S, Viñas JF. Incarcerated left-sided Amyand’s hernia and synchronous ipsilateral femoral hernia: first case report. Surg Case Rep 2023; 9(1): 15.

24. Heo TG. Amyand’s hernia combined with contralateral recurrent inguinal hernia: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2023; 102: 107837.

25. Drogge S, Kräutner J, Kremer M, Loupasis T, Manzini G, Kettenring M. Amyand hernia repair and negative pressure wound therapy. Ann Case Report 2023; 8: 1532.

26. Ijah RF, Sonye U, Nkadam NM. A long vermiform appendix in inguinal hernia sac (Amyand hernia): a case report in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. The Nigerian Health Journal 2023; 23(2): 692–697.

27. Bedaiwi L, Aljohani F, Badr G, Khan MLU. Amyand’s hernia; a case report in King Fahad Hospital, Medina. IJMDC 2023; 7(2): 374–377.

28. Krosser A, Ghirardo S. Amyand’s hernia and ischemic omentum due to omental torsion: a case report. Laparosc Surg 2023; 7: 11.

29. Teimouri A, Karkeabadi N. Amyand hernia with acute appendicitis and gangrenous mesoappendix: a case report. Authorea 2023; 2: 1–6.

30. Khurshid F, Hussain M, Chaudry S, Malik K, Touseef S. A case study on Amyand hernia: the uncommon form of hernia. Traditional Medicine and Modern Medicine 2023; 6: 39–42.

31. Alvi E, Khan I, Faridi SH, Ali I. Bilateral obstructed inguinal hernia with left Amyand’s hernia: a rare case report. Int J Med Pharm Case Rep 2023; 16(3): 26–30.

32. Hatampour K, Zamani A, Asil RS, Ebrahimian M. Amyand’s hernia in an elective inguinal hernia repair: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2023; 110: 108699.

33. Patoulias D, Kalogirou M, Patoulias I . Amyand’s hernia: an up-to-date review of the literature. Acta Medica (Hradec Králové) 2017; 60(3): 131–134.

34. Barut I, Tarhan OR. A rare variation of Amyand’s hernia: gangrenous appendicitis in an incarcerated inguinal hernia sac. Eur J General Med 2008; 5(2): 112–114.

35. Solecki R, Matyja A, Milanowski W. Amyand’s hernia: a report of two cases. Hernia, 2003; 7(1): 50–51.

36. Weber RV, Hunt ZC, Kral JC. Amyand’s hernia. Etiologic and therapeutic implications of two complications. Surg Rounds 1999; 22: 552–556.

37. Okur MH, Arslan MA, Zeytun H, Otcu S. Amyand’s hernia complicated with acute appendicitis: a case report and literature review. Ped Urol Case Rep 2015; 2(4): 7–12.

38. Okur MH, Karacay S, Uygun I, Topçu K, Öztürk H. Amyand’s hernias in childhood (a report on 21 patients): a single-centre experience. Pediatr Surg Int 2013; 29(6): 571–574.

39. Mewa Kinoo S, Aboobakar MR, Singh B. Amyand’s hernia: a serendipitous diagnosis. Case Rep Surg 2013; 2013: 125095.

40. Holmes M, Ee M, Fenton E, Jones N. Left Amyand’s hernia in children: method, management and myth. J Pediatr Child Health 2013; 49(9): 789–790.

41. Ofili OP. Spontaneous appendectomy and inguinal herniorraphy could be beneficial? Ethiopian Med J 1991; 29(1): 37–38.

42. Chatzimavroudis G, Papaziogas B, Koutelidakis I. The role of prosthetic repair in the treatment of an incarcerated recurrent inguinal hernia with acute appendicitis (inflamed Amyand’s hernia). Hernia 2009; 13(3): 335–336.

43. Vermillion JM, Abernathy SW, Snyder SK. Laparoscopic reduction of Amyand’s hernia. Hernia 1999; 3: 159–160.

44. Salemis NS, Nisotakis K, Nazos K, Stavrinou P, Tsohataridis E. Perforated appendix and periappendicular abscess within an inguinal hernia. Hernia 2006; 10(6): 528–530.