Acta humanitarica academiae Saulensis eISSN 2783-6789

2022, vol. 29, pp. 21–35 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/AHAS.2022.29.2

Transition and Transformation of the Slovak Society and Slovak Identity

Ivana Pondelíková

University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava, Slovakia

ivana.pondelikova@ucm.sk

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4557-0616

Abstract. The aim of this paper is to disseminate partial results of the Europe for Citizens / Share EU – Shaping of the European citizenship in the post-totalitarian societies: Reflections after 15 years of European Union enlargement project. The project focuses on linking the educational process, historical memory, and social change 15 years after EU enlargement. Based on in-depth interviews, we have examined the transformation of Slovak society since the Velvet Revolution (1989) and joining EU (2004). The focus is given to the historical background that led to the change of a regime. The transformation to a democratic society resulted in the formation of a new Slovak identity, which was examined through Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Respondents provided facts, thoughts, and their views of living in Slovak society since these two significant milestones.

Keywords: transformation, transition, society, identity, Slovaks, democracy, European Union, integration, cultural dimensions.

Slovakijos visuomenės ir slovakų tapatybės pereinamasis laikotarpis ir pokyčiai

Anotacija. Šio straipsnio tikslas – supažindinti su daliniais projekto Europa piliečiams / Pasidalinti ES – Europos pilietybės formavimas posttotalitarinėse visuomenėse: atspindžiai po 15 metų ES plėtros rezultatais. Projektas skirtas susieti ugdymo procesui, istorinei atminčiai ir socialiniams pokyčiams, praėjus 15 metų po Europos Sąjungos plėtros. Remdamiesi nuodugniais interviu, nagrinėjome Slovakijos visuomenės perėjimą nuo aksominės revoliucijos (1989 metai) iki įstojimo į Europos Sąjungą (2004 metai). Dėmesys skiriamas istoriniam fonui, lėmusiam santvarkos pasikeitimą. Virsmas į demokratinę visuomenę sąlygojo naujos slovakų tapatybės formavimąsi, kuri buvo nagrinėjama per Hofstedo suformuotus kultūrinius aspektus. Respondentai pateikė faktus, mintis ir savo požiūrį į gyvenimą Slovakijos visuomenėje per šių dviejų reikšmingų įvykių prizmę.

Pagrindinės sąvokos: perėjimas, pereinamasis laikotarpis, visuomenė, tapatybė, slovakai, demokratija, Europos Sąjunga, integracija, kultūrinis aspektas.

Received: 21/07/2022. Accepted: 30/12/2022.

Copyright © 2022 Ivana Pondelíková. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The mass protests of civil society in the late 1980s ended the era of communism in the European countries, which were politically and ideologically controlled by the Soviet Union. This created a space for a new beginning, which brought with it a new political order, as well as a fundamental breakthrough in the understanding of civil society. Slovakia has come through a difficult transformation process and by transitioning from a communist country to a democratic country; it has become a part of major international organizations and brought freedom to its citizens. How do the citizens of the Slovak Republic perceive these possibilities, how do they evaluate the changes in society, which do they consider to be positive or negative, and what impact has the transformation of society had on forming Slovak identity, were all questions we surveyed through in-depth interviews with 10 respondents as well as by using Hofstede’s 6-D model.

Theoretical background to phenomena of transition and transformation

The transition is characterized by the fact that during its course the political game is not defined by rules. Therefore, in countries that are in the process of transformation, it is not possible to define a specific type of regime, because it is a process that depends on the organization of actors and institutions and has far-reaching consequences for the future organization of the state (Tökölyová, 2019, p. 95). Transition occurs if we recognize at least two different systems (Wüsten, 1992, p. 51). In post-socialist societies, this means changing original socialist system to the target capitalist system. A typical feature of the transition is the adjustment of the regime by the authoritarian government itself to ensure a greater range of protected rights for individuals and groups, including elections and voting for new representatives. The holding of elections and the establishment of new legislative assemblies are generally considered to be the completion of the transition process (Lindberg, 2009).

The process of democratic transition should be linked to the process of consolidation of democracy. In the 20th century, the focus turned to the issues of consolidated civic society and promotion of democracy was connected to depolarisation of public life (Tökölyová, 2017, p. 141).

Transformation is a complex process that covers changes on economic, social, political level that influence demographical behavior of inhabitants. Transformation is an alternative and open process that we cannot say with certainty when it is completed and what the exact result will be, because it consists of several successive transitions within the same development (Rusnák & Korec, 2013, p. 398). Moravay summarizing the findings of other authors argues that the transformation process begins with a decision to move to a market economy and ends only when:

(1) The requirement of a functioning market mechanism is met.

(2) The requirement to generate strong sustainable growth.

(3) The requirement to eliminate distortions and defects, which will allow them to interact in equal terms with more advanced market economies (Moravay, 2005, p. 6).

The problem of determining the end of the post-socialist transformation depends on the definition of the target state of the transforming nation. This goal is shaped naturally during the course of transformation. In case of Slovakia, the transformation process can be observed in forming a small state, which is characterized by indicators such as population, size of the country and the share of gross world product (Rusiňák, 2010, pp. 94–102). Slovakia as a small state prefers using soft power tools in foreign relations and diplomacy. Building an image or a brand of the country and forming national identity of a small state is based on its history, ethnic and cultural aspects (Tökölyová & Kočnerová, 2017, p. 130). After the fall of the authoritarian regime, Slovakia has transformed into a democratic, politically and economically independent and perspective country. For transforming states that have undergone a revolutionary change in the system, it is necessary that other states perceive this change, recognize the new direction of the state (Ibid., p. 134), accept and recognize their national identity.

Research methodology and research sample

The aim of this paper is to disseminate partial results of the Europe for Citizens / Share EU – Shaping of the European citizenship in the post-totalitarian societies: Reflections after 15 years of EU enlargement project. The project focuses on contribution to a better understanding of the democratic social processes taking place in the European Union, both in the historical and contemporary dimension. Its main goal is to create a supranational debate and reflection on educational and social activities related to shaping European citizenship in post-totalitarian societies; historical memory, cultural heritage, and common European values; and demonstrating various approaches to common historical events and their effects. The project consortium is composed of the Jagiellonian University in Poland, University of L’Aquila in Italy, and Matej Bel University in Slovakia.

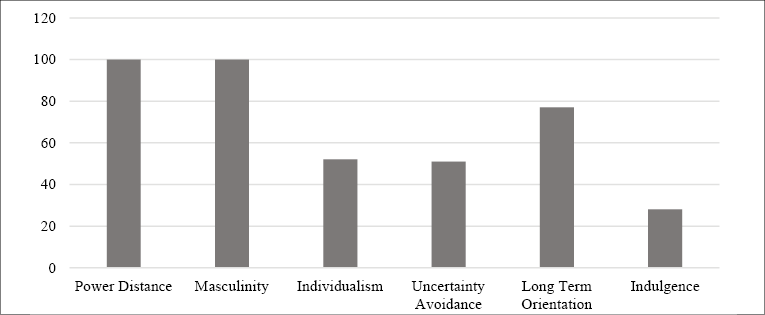

The research has mapped the educational process as “democracy seems to be the bearer of fundamental human and common values and is characterized as an effective approach to improve the quality of life, even if the basic question still remains that of how to teach it” (Rizzi et al., 2022, p. 149); and nature of the construction of the active civil society in the post-totalitarian reality of Central and Eastern Europe, covering the period of systemic transformations in the region from 1989 to social changes 15 years after EU enlargement (2004) examined by using in-depth interviews. In Slovakia, the focus is given to the historical background that led to the change of regime, which started with the Velvet Revolution (1989). The transformation to a democratic society resulted in the formation of a new Slovak identity, which was examined through Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Cultural dimensions are an important tool in the study of culture and national identity because they point to the context of the culture which an individual comes from. Currently, Hofstede provides the opportunity to compare cultures in the so-called 6-D model, which describes in detail the ways, manifestations, and norms of behavior in individual cultures. Based on this model, it is possible to create a characteristic of a certain country (see Figure 1) and its national identity.

The in-depth interview is an effective scientific research method that allows researchers to capture not only the facts but also obtain a deeper insight into the motives and attitudes of the respondents (Gavora, 2010). Since the research was carried out in three countries (Slovakia, Poland and Italy), the research team opted for the form of structured interview, in which the research areas and related issues are created in advance. All respondents answered the same questions in the same order. The first part of the interview focused on local democracy and respondents expressed their thoughts about changes in their town/city and civic engagement. The second part mapped the authoritarian and totalitarian past and respondents were expected to share their views on the transformation process, its advantages and disadvantages as well as the outcome of this process whether they consider their country democratic or not. The third part studied European integration and the formation of European identity. Slovak respondents provided facts, thoughts, and their views of living in Slovak society since two significant milestones (the Velvet Revolution and joining the EU). The advantage of this method is that the necessary information can be obtained in a short time and then compared and categorized with each other. The disadvantage is that the researcher cannot react flexibly and ask additional questions during this type of interview. The aim of this research was to find out subjective evaluations and opinions, without requiring expertise in this topic but not excluding it.

In qualitative research, the selection of a research sample is always intentional (Hendl, 2008). To achieve the highest possible degree of validity of the submitted research, we carried out the selection of respondents so that they fully met the criteria arising from the research objectives. We only included those respondents in the research who had personal experience with the studied phenomena, and we created 5 target groups:

(1) common people – family members, friends, acquaintances, or strangers;

(2) teachers;

(3) students;

(4) decision makers – people in leadership positions who directly affect the running of the city, school, business;

(5) leaders or members of NGOs – people active in civil society.

This research represents only a part of a comprehensive research, which, in addition to historical memory, includes mapping of educational processes about democracy at secondary schools, as well as a public opinion survey of 100 respondents performed online through the questionnaire, whose main task was to find out the answer to the question whether Slovak citizens can be considered active in the European context (Pecníková et al., 2021, p. 27). In addition to in-depth interviews, we have examined the shaping of Slovak identity based on Hofstede’s comparative research in the field of interculture. Based on Hofstede’s findings it is possible to describe a national identity. One of the well-known authors to describe the concept of national identity is Smith (1991), who sees recognizing a homeland as the basis and identification of the nation’s direction and identity as key, because this self-identification remains even at a time when the citizen does not live directly in the territory of his/her origin. Self-determination based on the value of creating a sense of uniqueness and belonging can subsequently be associated with a sense of political belonging (Tökölyová, 2019, p. 65). In the present research, we wanted to find out what is the attitude of Slovaks to changes in society since 1989.

Research results and their interpretation

Slovakia on its way to democracy

Slovakia has been an independent state for less than three decades. In the past (except for the Slovak state during World War II) it was either under the domination of another country or group of countries or in a joint union with the Czech Republic. After 1993, when Slovakia embarked on the path of economic, political, and social transformation, it was clear that it would not do without foreign aid and would not be able to function independently within Europe for a long time. It was not long before negotiations on Slovakia’s membership in the European Union began. On 1 May 2004, Slovakia became a member of the EU and since 1 January 2009 it has also been a member of the European Monetary Union, the Eurozone. The official currency became the Euro, which is considered one of the most tangible symbols of European identity.

Slovakia has been a democratic country since 1989, providing citizens with various rights and freedoms. Equality and freedom, which Slovaks had long awaited, are considered to be the most important benefits in a democracy. Gaining freedom was a difficult process, preceded by a long period of unfreedom (1939–1989). During World War II, Slovakia turned into an authoritarian state with fascist elements, with great powers accorded to President Jozef Tiso, and with Hlinka’s Slovak People’s Party took over all the power. Hruboň defines this regime from 1938 to 1945 as “originally a nationalist-authoritarian regime, which under the influence of domestic and foreign factors transformed into a regime of national-socialist (fascist) type and subsequently mutated into a hybrid regime without a clear political identity” (Hruboň, 2020, p. 336). The ideas of Nazism and fascism penetrated Slovak society and fundamental civil rights ceased to be respected, press censorship was introduced and freedom of speech did not exist. In short, Slovakia changed into a totalitarian regime. In the research, we have found out that frequently used terms such as Nazism, fascism, totalitarian regime, authoritarian regime are confusing for many. We asked about the difference between authoritarian and totalitarian regimes and also about what the regime was in Slovakia in the period from 1960 to 1989. Two respondents considered them to be identical, four respondents did not know the difference between them, and three respondents were aware of the difference. One of these three also deals with this topic professionally and explained the concepts as follows: “The authoritarian regime wants to control all institutions in the state, formally maintain democratic features such as parliament. The totalitarian regime is a complex reconstruction of society, institutions, the spiritual revolution of the nation. The totalitarian regime wants to control the people and ideologically indoctrinate them”. Eight of the respondents described Slovakia in the period from 1960s to the end of 1980s as a country with a totalitarian regime, two respondents thought that Slovakia was a country in which a hybrid form of both regimes operated.

In 1948, the Communists took absolute power and began to consolidate a totalitarian regime along the lines of the Soviet Union. Forty years under the red star meant for many a period of restriction of personal liberty, persecution, fear, and cruel punishment. General dissatisfaction led in January 1968 to a change called the Prague Spring. Alexander Dubček led the Communist Party at that time and under his rule, censorship was lifted, people were allowed to travel, religious life was revived, all moves which met with opposition from the Soviet Union. After a series of fruitless negotiations, Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia on the night of August 20–21, 1968. The period of normalization brought a lot of suffering, but nevertheless many refer to it as the “golden good times”. We asked respondents what they consider to be the main positives of this period. Surprisingly, the youngest respondent said that people were disciplined and, together with two other respondents, agreed on job security. The other seven do not consider anything positive of that era. Apart from the negatives, as one of the respondents stated that socialism is based on the philosophy of collectivism, and it presupposes a positive effect of solidarity. The respondent added that people were closer to each other than today, where work and property come first. However, life in a totalitarian society restricts personal freedom in particular, which was confirmed by half of the respondents. Totalitarianism is characterized by drastic means of total control. Regardless of specific national traditions or the specific spiritual source of their ideology, the totalitarian form of government has always changed classes to masses, replaced the party system with a dictatorship, shifted the centre of power from the military to the police, and pursued foreign policy to rule the world (Arendtová, 2018, p. 126).

Opponents of the regime and their families were bullied yet they were not silenced. The activities of dissidents initially focused on the dissemination of forbidden professional and philosophical texts. On January 1, 1977, the civic initiative Charter 77 emerged from the environment of Czech intellectuals, criticizing the Czechoslovak regime for violating human rights. The Communists held the power tight and relied on the Soviet Union. In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev was elected the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, launching a series of reforms known as perestroika (reconstruction). Together with the policy of glasnost (openness), they meant the reconstruction of an ossified regime, but also the opportunity to freely express one’s opinions. The opportunity to express oneself freely was only a step towards the fall of communism. Gorbachev’s policy led to the collapse of the Soviet Union and he did not intervene militarily in the changes going on in socialist countries. In 1989, all of the countries of the Soviet bloc experienced these, with free elections prepared in Poland, Hungary opening its borders with Austria, the dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu being executed in Romania, the Berlin Wall fell in Germany, which led to the unification of the two German states (the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic) in 1990. The situation in Czechoslovakia could be described as “the atmosphere of anticipation in the wake of events” in its “neighbouring socialist countries” (Carter, 1990, p. 254). Following the mentioned events, the Czechoslovak alliance with the Soviet Union, which was supposed to be “forever”, also ended.

The Revolution that was going on at the time was labelled “Velvet” because of its peaceful course. The ethos of the revolution manifested itself in three ways: in unity, in the social desire for freedom, and in nonviolence. Both the Czech Civic Forum and Slovak Public Against Violence were “all loosely-knit organizations without any clear goals or strategies and without even clear membership. Neither of these organizations had worked out a political or economic program during the initial period of mass demonstrations. Rather than striving to conquer the state, they demanded further elections and the resignation of the most hard-line leaders” (Saxonberg, 1999, p. 30). The process of power-transition and country’s gradual democratization could be seen as a “result of ‘negotiated revolution’ and, therefore, a native product created ‘at home’ rather than imported” (Pop, 2013, p. 357). One of the most significant power shifts was the election of the dissident and playwright Václav Havel as President of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. Sekerák (2018, p. 25) adds “almost none of the past official have been punished for crimes of the totalitarian regime”. On the contrary, the outcome of these events, many of them (or their children) have become successful business people or politicians, especially thanks to the social capital they have accumulated through the years (Ibid., p. 15).

Slovakia embarked on the path to democracy, but while in 1989 the violence against communism, imprisonment behind the Iron Curtain, repression against free thoughts, punishment for freedom of speech and discrimination were fought, today we are struggling with the consequences of the 1990s, which allowed the country to be looted, in which the power was taken over by the mafia and oligarchy. We asked the respondents whether Slovakia could be considered a democratic country. Only one answered, “yes”. Four respondents stated that Slovakia is a de jure democratic country, but de facto only has the elements of democracy. They do not consider Slovakia to be an advanced democratic country; they even claim that “Slovakia was not ready for transformation”. The transformation brought not only economic but also political problems. Imperfect laws have been abused, especially for enrichment. Crime, unemployment and corruption have risen to enormous proportions. That time, the United State of America Secretary of State Madeline Albright assessed the situation in Slovakia very harshly: “Currently, there is a black hole on the map of Europe called Slovakia”. The 2020 parliamentary elections reflected a desire for change. People believe that the new government will expose the fraud and unfair practices of previous governments and establish justice in a country where law and order did not have a strong position. One respondent said that “change is necessary”. Currently, the threat is posed by the parliamentary party People’s Party Our Slovakia, which has features of nationalism and fascism. Seven respondents consider this party’s presence in parliament to be incorrect. One respondent considers this to be a positive phenomenon. In a democratic society, there is no room for such radical ideas and attitudes. If Slovakia wants to become an advanced democracy, it must create an open, democratic society in which the law applies equally to everyone, human rights are respected, social responsibility is promoted and space for a functioning civil society is created, to which European integration makes a significant contribution.

The question of identity1

Identity is a modern phenomenon that did not exist in the Middle Ages as we know it today. In an agrarian society, people were bounded by social class, religion, and local ties to the lord of the manor. All of this began to change with the rise of industrial society; these older ties dissolved, and society needed a different kind of glue to hold it together (Fukuyama, 2012). This glue was typically formed of language and culture, as they create new bonds so that people could communicate with each other and live together in a pluralistic, multicultural and modern society. Identity is a key to understand human beings, their thoughts and views, but also to perceive the life of the communities in which they live.

Personal identity is primarily associated with the environment in which a human being is born. Over time, the institutional aspect of identity develops, allowing a person to choose, based on their own decisions, what will shape their identity. In today’s individualized society, therefore, there is a shift in emphasis from primordiality, the aspect of identity, which is given, permanent, inherited or fixed, to instrumentality, a basis of identity which one chooses and forms. This does not mean that concepts of essentialism are no longer alive and important, but it leads to the view that these two approaches to the study of identity are not completely mutually exclusive. Identity can take various forms, like national, transnational, ethnic or religious, but also modern forms of identity as such as digital, intercultural, and hybrid.

National and transnational identity

Identity is the key to understand human beings as well as the communities in which they live. National identity is more strongly tied to the primordial aspects of race, ancestors, common language, religion, and territory. It can be defined as the identity of a person who perceives his/her affiliation to a particular nation or state and is thus associated with a sense of solidarity. From a functional point of view, we can classify it among the main group of identities. National identity, like all other identities, is reflected in the linguistic expression of the individual on various formal and informal occasions. In terms of content, it is about emphasizing the differences between members of a particular nation and other nations, recalling a common past, expressing an emotional relationship with own country, and highlighting national culture and identifying the country and the nation into one whole.

The global mobility of people, information, and consumer goods is one of the forces, which have provoked a widespread intensification of cultural exchanges within and beyond the border of the nation. Regarding this context, the concepts of transnationalism and transculture have occurred in recent years and have often been adopted to describe the new identity formation process. In an era of global migration, it is possible to be connected to several places in both the real and the virtual world. Thus, transcultural identity can be defined as an individual identity formed beyond national and virtual borders as well as cultural borders that includes religion, language and ethnic background.

In the 1990s, the American political scientist Samuel P. Huntington divided the world into civilization units that create transnational forms of identity. This division helps to classify individual units on the basis of similar cultural parameters, but it does not take into account the specificity and uniqueness of individual countries. It also contributes to the creation and consolidation of stereotypes and prejudices.

European integration and its impact on Slovak identity

The issue of identity is a current problem, especially in the European cultural space, under the influence of tensions brought about by multiculturalism and pluralism, as well as the mutual misunderstanding of different cultural identities. European identity is a broader concept than national identity and is based on the principle of unity in diversity. The majority of the population of the European Union prefer their national identity to a European identity. The exception, however, is among young people, who are more often keen to identify as Europeans. The EU is constantly changing its territory, and under this influence the identity of individual nations is changing as well.

By joining the EU, Slovakia has taken an important step in its development. We were interested in whether European integration leads to the development of democracy in Slovakia. Half of the respondents agreed, three disagreed and two said that “it should lead to the development of democracy”. They consider the development of infrastructure, the revitalization and reconstruction of monuments, the opportunity to travel, study and work abroad, and the use of EU funds to be the greatest positives of European integration, but on the other hand the bureaucracy associated with them is considered to be a considerable negative factor. Respondents further stated that in addition to the fact that people in Slovakia do not understand European regulations and directions, they still complicate them. They consider the “brain drain” to be another negative. Pecníková (2015, p. 735) states that “as a result, there is a silent emigration in Slovak society, when 25 % of young people over the age of 18 go to work abroad”. Two respondents said that those who stayed at home feel threatened by migrants and are afraid of otherness. Generally speaking, the reluctance and xenophobic attitudes of the Slovak population are not only confirmed by numerous public opinion polls, but often also by the opinions and experiences of tourists, as well as by foreigners living in Slovakia (Bitušíková, 2009, p. 36). One respondent stated that there are no positives of European integration and considers it as a suppression of national sovereignty.

The issue of national identity is also related to European integration. Half of the respondents feel that their national identity is endangered, claiming that “typical Slovak things are disappearing”. The other half agrees that the EU, as the representative of a united Europe, respects the identity of each country based on its motto “united in diversity”. In order to implement integration policy, the EU is transforming Europe into new geopolitical structures, removing economic-administrative barriers and political borders. It also manages, not with the same speed and intensity, to remove barriers between the citizens and the cultures they represent. What still makes citizens different is their identity based on ethnic, cultural, religious, and national grounds. Six respondents consider themselves Europeans, respectively they consider the European and Slovak identities to be “two connected vessels”, and they cannot imagine that Slovakia would not be a part of the EU. European identity is a phenomenon that often appears in the discussions of the professional public, but also in society as a whole. Questions arise as to whether European identity exists, on what foundations it is built, whether it is merely an artificial construct or does it actually live in the consciousness of the citizens of the individual states of a united Europe, and whether national and European identities can coexist (Sekan & Gabura, 2013, p. 132). Delanty (2012) states that the term European identity tends to be replaced by the term “spirit of European”, reflecting the soul of the European. As Pecníková (2017, p. 46) states, some experts consider European identity to be only complementary (Herrman, 2004; Risse, 2011), which complements only national and regional identities. European states must define or redefine who they are, where they are heading so that they do not lose their own identity, they remain themselves, but also a part of a large unit.

Characteristics of Slovak national identity through Hofstede’s cultural dimensions2

Cultural dimensions are an important tool in the study of culture and national identity, because they point to the context of the culture from which one comes. At present, Hofstede provides the opportunity to compare cultures in the so-called 6-D model, which describes in detail the ways, manifestations and norms of behaviour in individual cultures. Based on this model, it is possible to create a characteristic of a particular country and its national identity.

Figure 1. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions

Source: own processing according to Hofstede (2021)

Power distance

A high score in this dimension means that Slovaks generally accept authorities and superiors, rarely express their opinion and are not accustomed to opposing them. This behaviour is the result of the socialist past, which was confirmed by the respondents. After 1989, there were changes not only in the regime, but also in people’s thinking and behaviour. As one respondent stated the change was needed. The young generation is more ambitious and “braver” than the previous one. They have experience of studying abroad, they travel much more and get to know other cultures. They work in international companies where a company-oriented performance policy is applied, employees participate in the management of the company and do not have to be afraid of expressing their opinions.

Masculinity versus femininity

In masculine societies, assertiveness and toughness are preferred in connection to material success, while in feminine societies modesty and interest in quality of life are preferred. Masculinity is typical of cultures, which gender roles are strictly differentiated in, femininity for cultures where gender roles overlap. A high score in this dimension indicates that the company is driven by competition, competitiveness and success. People are also educated to achieve their goals. The motives for achieving success are mainly related to better financial evaluation. The respondents confirmed that Slovaks want to take care of their families, so they spend more time at work. Material values have become more important in Slovak society than interpersonal relationships. This change in people’s minds was also caused by the previous regime, in which people felt the material limitations of goods and services now commonly available.

Individualism versus collectivism

Individualist societies do not usually feel a great commitment to the family, while collectivist societies form cohesive groups. This dimension correlates with the amount of gross domestic product per person. The higher the standard of living in a country is, the higher the level of individualism of the members of the community is. Since 1989, we can observe a change from collectivism to individualism in Slovak society, which, as the respondent stated, is also caused by the possibilities that came with joining EU. Young people are not afraid to travel for work or study, gradually breaking family ties. They take responsibility for their decisions, they are proactive at their work, independent and are expected to express their individual opinion. If they work in an international environment, it is common for them to adapt to a foreign culture.

Uncertainty avoidance

This dimension reflects how people feel threatened by uncertainty and unknown impulses and situations. Slovakia achieved a score in the middle of the scale, which does not indicate clear preferences. Based on this finding, we cannot determine exactly how Slovaks react to changes, resp. they accept challenges and to what extent they are willing to try something new or different. Based on the research results, it can be confirmed that Slovakia is in the middle regarding perceiving unknown and unexplored spheres.

Long term orientation

According to Hofstede’s research, Slovakia is a pragmatic country in which most people believe that the truth depends on a specific situation, context, and time. Slovaks tend to save, invest, and do not strictly adhere to their own traditions as confirmed by the research that typical Slovak tradition are disappearing. Pragmatism expresses how people cope with the fact that much of what is happening around them cannot be explained. In a pragmatic society, most people do not need to have everything explained, believing that it is impossible to fully understand the complexity of life. The challenge is not to know the truth, but to live an honest and decent life. Pragmatic societies believe that truth largely depends on the particular situation, context and time. In addition to this, these societies are able to accept inconsistencies, adapt to circumstances and conditions, postpone, save, invest and persist in achieving results (Hofstede et al., 2010, p. 275). On the other hand, in normative societies, most people have a strong desire, even the need to have explained as much as possible. They have a keen interest in establishing absolute truth and personal stability. In such a society, there is a clear respect for social conventions and traditions, a focus on achieving rapid goals and a low tendency to save for the future.

Indulgence

Indulgence means in particular general enjoyment of life, leisure, entertainment, holidays, etc. The value of the indulgence index expresses how a certain society is able to renounce them. Societies that suppress the satisfaction of their needs do so by adhering to strict social standards (Ibid., p. 281). According to Hofstede’s (Hofstede insights online) findings, Slovakia ranks among the countries and cultures that are characterized by self-control and renunciation of pleasures. We would like to point out that changes have also taken place in this area, as Slovaks, especially the younger generation, decide how they spend their free time and place increasing emphasis on the quality of life. Social life has become very important for Slovaks in recent years.

Given that Slovakia has been in the process of transforming society since 1989, some of Hofstede’s findings could be debated. Changes occurred not only in the regime, but also in people’s opinions, attitudes and behaviour. As we have confirmed by research, the younger generation is not only considered Slovaks, but also Europeans. They do not recognize only one national identity, they are no longer connected only with their own nation, but they acquire the multiple identity (Moree, 2015, p. 15). Especially among the younger generation of Slovaks, a gradual trend towards the cosmopolitan citizenship can be observed. The cosmopolitan citizenship combines humanistic principles and norms with equality, while emphasizing diversity (Pecníková, 2017, p. 19).

Conclusion

Slovakia has undergone a path of change that is slowly and gradually helping to create a civil society that can provide adequate space for active citizens. Forming a civil society in Slovakia is created on the basis of dissolving socialistic establishments (Tökölyová & Sedláková, 2005, p. 35). Transition to democracy expresses wished result of this process (Tökölyová, 2017, p. 140). Slovaks freed themselves from the communist regime and set a democratic one. Regarding the statements of respondents, the research results showed that nowadays, Slovakia is a good country for the ambitious people, however the rights are above the duties. The older generation finds it difficult to accept personal responsibilities for their lives as they were used to for a state support. Comparing two regimes, in the past Slovakia was a good country for party supporters and the West was considered evil. At present, the East represents evil and the presence of People’s Party Our Slovakia in parliament is generally considered to be a threat.

Transformation of the society is a complex process on economic, political and social level that is in Slovak conditions ongoing. It is visible in shaping of the national identity that undergone various phases from accepting independence to turbulent era of “a black hole” towards being presented as “Switzerland in the Central Europe” up to “Tatra tiger”. Identity of a nation is reflexive, because it is formed in an interaction with perceiving of the others. Nation branding is a new phenomenon, which mirrors positive and negative image of a country. Nowadays, Slovakia is perceived as a small state, economically orientated to automobile industry, which draws on the rich natural and cultural heritage (Tökölyová & Kočnerová, 2017, p. 145). However, its negative image is that there is still much corruption, insufficient health care system and regional differences. Moreover, Slovakia cannot get rid of the label of post-socialist country. A unique phenomenon is that Slovakia has managed to maintain its independence, and what is even more essentially is that Slovakia is still keeping its own language.

Positive turn is mainly among the young ones, who are moving towards cosmopolitan citizenship (Pecníková, 2017, p. 75), which recognizes the European values. A cosmopolitan citizen combines humanistic principles and norms with equality, while emphasizing diversity. Monolithic identity is vanishing as international migration leads to the emergence of transnational communities and culturally diversified societies. A citizen does not have only one national identity, he/she is no longer connected with one nation, but we are talking about its so-called multiple identity.

For the needs of the submitted research, we have chosen the qualitative method of research. In the social sciences and humanities is increasingly used as a complementary, but also the main method of research of selected phenomena. Still, it is sometimes understood only as a complement to traditional quantitative research, sometimes as its opposite. Qualitative research is considered an emergent and flexible type of research (Hendl, 2008, p. 256). However, data collection and analysis take place over a longer period of time, so the research process is longitudinal in nature.

We consider it appropriate to list here a few of the limitations or shortcomings of the presented research. The weakness of any qualitative research is its reliability, i.e. the accuracy with which the researcher can interpret what he/she heard or read, so we interpreted the data obtained as respondents’ statements about a certain phenomenon. We see the strength of the presented research in its interdisciplinary nature. We are convinced that the results of research can be applied in several scientific disciplines, such as cultural studies, history or social sciences. More insight into the research results of the whole project can be found in the scientific journal Politeja 1(76) (2022) edited by Sondel-Cedarmas, Fijał, and Mach, and edited book Post-totalitarian Societies in Transformation. From Systemic Change into European Integration (2022) by Sondel-Cedarmas, Pożarlik and Mach. Additionally, Kultúra – identita – občianstvo v kontexte transformácie Slovenska 15 rokov po vstupe do EÚ (2021) by Pecníková, Pondelíková, and Mališová also provides valuable research outcomes.

References

Arendtová, H. (2018). Pôvod totalitarizmu, I–III. Bratislava: Premedia.

Bitušíková, A. (2009). Spoločné kontexty integrácie cudzincov na Slovensku. Kultúrna a sociálna diverzita na Slovensku, II. Cudzinci medzi nami, Banská Bystrica: Ústav vedy a výskumu Univerzity Mateja Bela v Banskej Bystrici.

Carter, F. (1990). Czechoslovakia. Geographical prospects for enemy, environment and economy. Geography, 75(3), 253–255.

Country comparison. Slovakia. Hofstede insights online. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/slovakia/

Delanty, G. (2012). Europe in an age of austerity: Contradictions of capitalism and democracy. International Critical Thought. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/21598282.2012.730371

Fukuyama, F. (2012). The Challenges for European Identity. The Global Journal. http://www.theglobaljournal.net/article/view/469/

Hendl, J. (2008). Kvalitativní výzkum. Základní teorie, metody a aplikace. Praha: Portál.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J. & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Oragnizations. Software of the Mind.

Intercultural Cooperation and its Importance for Survival, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hruboň, A. (2020). Prečo slovenská historiografia a spoločnosť potrebujú novú paradigmu európskeho fašizmu? Poznámky (nielen) k monografii Jakuba Drábika Fašizmus. Historický časopis, 68(2), 335–351.

Lindberg, S. (2009). Democratization by Elections. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Moravay, K. (2005). Stratégia a priebeh ekonomickej transformácie na Slovensku. Ekonomický časopis, 53(1), 5–32.

Moree, D. (2015). Základy interkulturního soužití. Praha: Portál.

Pecníková, J., Pondelíková, I. & Mališová, D. (2021). Kultúra – identita – občianstvo v kontexte transformácie Slovenska 15 rokov po vstupe do EÚ. Banská Bystrica: Koprint.

Pecníková, J. (2017). Aktívne občianstvo: európske či lokálne? Banská Bystrica: Dali BB.

Pecníková, J. (2015). Občianska spoločnosť na križovatke. Smer Európa alebo ... ? Sociálne posolstvo Jána Pavla II. Pre dnešný svet. Ružomberok: Verbum.

Pondelíková, I. (2020). Úvod do medzinárodných kultúrnych vzťahov a interkultúrnej komunikácie. Banská Bystrica: Dali BB.

Pop, A. (2013). The 1989 Revolution in retrospect. Europe-Asia Studies, 65(2), 347–369.

Rizzi, P., Nuzzaci, A. & Natalini, A. (2022). Democracy between spaces of citizenship and civic competences. Two Explorations With Privileged Witnesses In Italian Context. Politeja, 1(76), 147–156.

Rusiňák, P. (2010). Malé štáty v medzinárodných vzťahoch a ich bezpečnosť. Almanach (Actual Issues in World Economics and Politics), 5(2), 94–102.

Rusnák, J. & Korec, P. (2013). Alternatívne koncepcie postsocialistickej transformácie. Ekonomický časopis, 61(4), 396–418.

Saxonberg, S. (1999). The ‘Velvet Revolution’ and the limits of rational choice models. Czech Sociological Review, 7(1), 23–36.

Sekan, F., & Gabura, P. (2013). Teoretický koncept európskej identity. Dimenzie občianstva Európskej únie, Banská Bystrica: Vydavateľstvo Univerzity Mateja Bela v Banskej Bystrici.

Sekerák, M. (2018). The Velvet Revolution and the Centre/Periphery Model: The Case of South Bohemia.

Politické vedy, 21(4), 1335–2741.

Smith, A. (1991). National identity. London: Penguin Books.

Sondel-Cedarmas, J., Fijał, M. & Mach, E. (2022). Politeja, 1(76). https://journals.akademicka.pl/politeja/issue/view/285

Sondel-Cedarmas, J., Pożarlik, G. & Mach, E. (2022). Post-totalitarian Societies in Transformation. From

Systemic Change into European Integration. Warsaw : Peter Lang.

Tökölyová, T. & Kočnerová, M. (2017). Význam národnej identity pre zahraničnú politiku malého štátu v

globalizovanom svete. Formovanie identity v čase a priestore. Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského.

Tökölyová, T. & Sedláková, L. (2005). Development of the civil society of the Visegrad region. Social,

Economic and Political Cohesion in the Danube Region in Light of EU Enlargement. https://www.drcsummerschool.eu/proceedings?order=getLinks&categoryId=4

Tökölyová, T. (2017). Democratic transition – Case of Czechoslovakia. Democratic transition in Slovakia:

Model situation for challenges of Ukraine a democratic transition. http://www.vip-vs.sk/images/dokumenty/nf

democratic-transition-in-slovakia.pdf

Tökölyová, T. (2019). Výzva napĺňania rozvojového potenciálu tichomorských demokracií. Bratislava:

Central European Education Institute.

Wűsten, H. (1992). Transitions. Changing Territorial Administration in Czechoslovakia: International

Viewpoints. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.