Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2024, vol. 53, pp. 106–127 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2024.53.8

Rūta Girdzijauskienė

Klaipėda University, Lithuania

E-mail: girdzijauskiene.ruta@gmail.com

Liudmila Rupšienė

Klaipėda University, Lithuania

E-mail: liudmila.rupsiene@ku.lt

Milda Ratkevičienė

Kaunas University of Technology, Lithuania

E-mail: b_milda@yahoo.com

Abstract. The healthcare system has long discussed the need to remove barriers faced by people with disabilities, however, health workers are often still not prepared to efficiently work with such people, and their education is still inadequate. This article explores future health workers’ understanding of the work with people with disabilities. The research study included five students from institutions of higher education studying in programmes training health workers. Research analysis included collages by two groups, transcripts of their presentations and researcher field notes. Analysis of the research study has helped to identify the topics of contextuality of professional activity and professional agency. When considering their future professional work with people with disabilities, students paid attention to the geographical (local), social and political contexts. The agency in the professional activity was expressed weakly. Research participants introduced several ideas how it would be possible to solve problems of people with disabilities. However, they did not consider actions how it could be done, nor did they make a connection between the changes in the healthcare system and their future professional activities. The article raised a question how to consolidate the education of future health specialists so that, after graduation, they would be able to work more efficiently with people with disabilities and meet their needs.

Keywords: healthcare education, collage method, people with disabilities.

Santrauka. Sveikatos sistemoje seniai diskutuojama, kaip pašalinti kliūtis, su kuriomis susiduria žmonės, turintys negalią. Sveikatos sistemos darbuotojų edukacija šiuo požiūriu iki šiol yra nepakankama ir todėl šie darbuotojai dažnai yra nepasirengę efektyviai dirbti su tokiais žmonėmis. Šiame straipsnyje nagrinėjama, kaip būsimieji sveikatos sistemos darbuotojai supranta jų darbą su žmonėmis, turinčiais negalią. Tyrime dalyvavo penki studijų programų, rengiančių sveikatos darbuotojus, aukštesnių kursų studentai. Tyrimo duomenų analizei naudoti dviejų grupių koliažai, jų pristatymo transkripcijos, tyrėjų lauko užrašai. Analizuojant tyrimo duomenis išskirtos profesinės veiklos kontekstualumo ir profesinio agentiškumo temos. Svarstydami apie būsimo profesinio darbo su žmonėmis, turinčiais negalią, paskirtį studentai atkreipė dėmesį į geografinį (vietos), socialinį ir politinį kontekstus. Profesinės veiklos agentiškumas, jų supratimu, silpnas. Tyrimo dalyviai pateikė keletą idėjų, kaip būtų galima prisidėti prie negalią turinčių žmonių problemų sprendimo. Tačiau nesvarstė, kaip tai turėtų būti daroma, sveikatos sistemos pokyčių nesiejo su savo būsima profesine veikla. Straipsnyje buvo keliamas klausimas, kaip stiprinti būsimųjų sveikatos darbuotojų edukaciją, kad baigę aukštąsias mokyklas jie gebėtų efektyviau dirbti su negalią turinčiais žmonėmis ir būtų kuo geriau atliepti šių žmonių poreikiai.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: sveikatos edukacija, koliažo metodas, žmonės su negalia.

_______

Acknowledgement. This research is funded by the European Social Fund in the framework of the activity “Improvement of Researchers’ Qualification by Implementing World-Class R&D Projects” of Measure No. 09.3.3-LMT-K-712.

Received: 10/04/2024. Accepted: 10/07/2024

Copyright © Rūta Girdzijauskienė

World Health Organisation of the United Nations has currently started putting increasingly more emphasis on the fact that health is not only the birth right of every person and an important element of life and adequate functioning in it, but also one of the most important priorities of each country individually and the entire world in general, encouraging growth, development and the overall well-being of people (World Health Organisation, 2015, 2016). Therefore, in this context, the disability issue becomes increasingly more relevant when looking for the ways to solve the problems of people with disabilities, improving and promoting their integration, quality of life, accessibility of healthcare, while also contributing to the sustainable development of the humankind, growth of economy and the well-being of the humanity in general. When formulating its policies regarding health/disabilities, World Health Organisation (2015) adopted the following position and has been encouraging the states to adhere to it: disability is not simply a social or biological phenomenon; it is a general problem of the public health, an issue of human rights, and a development priority.

According to the data of World Health Organisation (2015), there are over 1,000 million (i.e., 1 billion) people with disabilities – around 15 per cent (or one out of seven) people living in the world. According to the data of 2011, 2–4 per cent of all people with disabilities have experienced great functioning difficulties (World Health Organisation, 2011). According to the calculations of World Health Organisation (2011), the number of people with disabilities grew from 1970 to 2010 by, respectively, from 10 to 15 per cent, and this was influenced by such factors as life expectancy and the growth of chronic diseases related to it, as well as the improved system to diagnose disabilities. According to the communication by the European Commission (2015), around 80 million people with disabilities cannot be fully involved into the public and economic activities, and, due to the limited opportunities of employment, the poverty level of people with disabilities is as much as 70 per cent higher than the average. With Lithuania in mind, and according to the data of the Ministry of Social Security and Labour of the Republic of Lithuania (2019), at the end of 2017, 242,000 people received disability pensions in Lithuania (of whom, around 47 per cent males and 53 per cent females, 8.5 per cent of all residents of the country), while the number of disabled children was estimated at around 14,800 (2.9 per cent of all children in the country). Statistical indicators prove once more that a relatively significant part of our society is being affected in its everyday life by one disability or another. Therefore, ensuring the universal rights of people with disabilities must be at the constant centre of policy-makers, practitioners, and scientists.

Within the last decade, the rights of people with disabilities have been declared both globally and individually by each country. One of the most important documents regulating the rights of people with disabilities is the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006). Not only does the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) declare the rights of people with disabilities, but it also details the obligations for countries that have ratified this concept. This Convention (2006) emphasises that the countries hereby are obliged to ensure proper healthcare for people with disabilities, without discriminating them against their disability, while health workers must provide them with the services of the same quality as they do to all other persons. Therefore, it can be stated that even though the aim is to make sure that the rights of people with disabilities on the global level would be equally understood and enforced (in the specific case of this article, in the healthcare system), still, the main responsibility when shaping this policy related to the rights of people with disabilities belongs to the countries themselves.

According to Article 7(1) of the Law of the Republic of Lithuania on the Social Integration of the Disabled (2004), “to ensure equal rights of people with disabilities in the area of healthcare, services provided to people with disabilities in the healthcare system shall be of the level and in accordance with the same system as to other members of the society.” According to the Public Audit Report of the National Audit Office of the Republic of Lithuania (2018), it is stated that, currently, there is a lot of attention being paid to the quality of healthcare services in Lithuania. The aim is to make them safe (safety in the sense of ‘not causing harm’), effective (efficiency here refers to the provision of the best result), accessible (accessibility in this context means that the services are to be provided at the right time, the right place, while also using the most relevant competences and resources), patient-oriented (orientation to the patient, taking into consideration his or her individual expectations, priorities and community culture). However, while the position of people with disabilities in the healthcare system is a constant subject of both scientific and practical discussions in Lithuania and the entire world, their equal rights to the healthcare services are not ensured completely.

According to the communication by the United Nations (no date), people with disabilities who need to receive healthcare services are still facing quite a few serious challenges: difficult physical access to healthcare institutions, lack of proper transport, as well as negative approach of healthcare service providers to them. In this case, it is noteworthy that the negative attitude of health workers, according to Santoroa et al. (2017), can be related to the fact that health workers are still not properly equipped to work with people with disabilities, and their education in this area is still insufficient. According to the World Health Organisation (2016), the entire world feels a clear need to increase the ability of health workers to provide human-oriented services, which requires socially accountable education that includes training on how to work in a team, ethical practice, ensuring communication which is sensitive to rights, gender and culture and patient empowerment, because investment into the education of health workers ensures the economic growth of the country. Therefore, the proper training of health workers focuses not only on the health sciences but also, as it is very important, on people with whom they will have to work, communication with them and the work ethics, etc. It must become a self-evident thing just like the development and progress of health sciences.

In Lithuania, health workers are trained at four universities as well as six universities of applied sciences. According to the data of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Lithuania (no date), university studies in the relevant field take from 4 years (studies of public health, nursing and rehabilitation), to 6 years (medical studies); medical residency studies take (depending on the specialty) 3 to 6 years, dentistry – 3 years, master studies of public health, nursing and rehabilitation span over two years; the duration of doctoral studies is 4 years; non-university studies take from 2 to 3.5 years (depending on the study programme). General requirements for the training of health workers are regulated by the legislation of the Republic of Lithuania, namely, the General Requirements for Study Programmes (2016), the Description of General Requirements for Degree-Awarding First Cycle and Integrated Study Programs (2010), and the Description of General Requirements for the Master’s Study Programs (2010).

According to the List of Branches Comprising the Study Fields (2010), there are ten study fields established in Lithuania (Medicine, Dentistry, Professional Oral Hygiene, Public Health, Pharmacy, Rehabilitation, Nutrition, Nursing, Medical Technology, Medicine and Health, and the title of the latter matches the name of the group of the study area), branching out into 22 subsequent areas of studies. All fields of studies assigned to the group of Medicine and Health fields of studies (except for Medicine and Health and Medicine Technologies) are regulated by the descriptions of the fields of studies approved by the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport of the Republic of Lithuania, and this means that all these institutions of higher education that offer study programmes in these fields of studies must comply with the provisions established in these descriptions. Currently, there are no descriptions of either Medicine and Health or Medicine Technology fields of studies formally approved by the Minister of Education, Science and Sport of the Republic of Lithuania. According to the website of the Centre for Quality Assessment in Higher Education (2015, 2018), it is planned to implement the project Development of a System for the Description of Studies (SKAR-3) by 2021; the project was expected to involve drafting, preparation and updating of documents regulating the study areas and thus completing the development of a system of descriptions of the study areas of Lithuania.

The analysis of documents regulating the training of health workers has revealed that they lack focus on people with disabilities. From all the descriptions of the group of the Medicine and Health study areas, only the descriptions of Medicine, Rehabilitation and Nursing refer to people with disabilities to a minimum extent:

• In the Description of Medicine Field of Studies (2015), one of the special outcomes of studies claim that, after the graduation, the specialist will be able to “convey information for patients, patient’s relatives, the disabled and colleagues in a clear, sensitive and efficient manner, including written and spoken communication (also applicable to medical documentation).”

• In the Description of the Rehabilitation Field of Studies (2015), it is stated that one of the personal abilities of Cycle 2 graduates to be achieved is an ability to make independent decisions in situations that require to demonstrate the understanding combining various scientific disciplines, deep and critical assessment of scientific knowledge and experience solving problems of health care, rehabilitation and integration of the disabled, modelling strategies to solve problems.”

• Description of the Rehabilitation Field of Studies (2015) defines that the proper organisation of the study programme requires a specific material basis, and one of the requirements is the equipment for the people with disabilities.

• In the Description of the Nursing Field of Studies (2015), it is stipulated that “knowledge, skills and values of nursing and obstetrics can be applied to all levels of personal healthcare institutions, providing healthcare services to all age groups of patients; in healthcare institutions of national defence, and the system of home affairs; institutions of social services – foster home of healthy and disabled people of all ages, and private personal healthcare institutions.”

Therefore, it can be stated that orientation towards people with disabilities in documents regulating the training of health workers is eminently minimal. It is noteworthy that this problem is relevant not only in Lithuania. According to the World Health Organisation (2016), all countries independently from their sociocultural level are facing certain issues with the training of health workers. There is quite a number of research proving how important it is to properly train health workers to work with people with disabilities, yet countries constantly face the fact that the legal system designed to train these employees is still poorly addressing the issue. For example, research carried out in Greece from 2014 to 2016 focusing on nursing and medicine students as participants revealed that, according to Kritsotakis et al. (2017), the attitude of students in healthcare programmes towards people with disabilities in Greece is negative, and it in its turn causes other problems – an unfavourable attitude, the minimal level of communication with people with disabilities, and insufficient quality assurance. A similar situation can be found in the USA, where, according to the research carried out by Sarmiento et al. (2016), most schools training health workers do not have specific programmes oriented towards people with disabilities (except for individual cases, when disability is perceived as a disorder of deficiency that needs to be treated). It is also of importance that while it is known and scientifically based that the ensurance of efficiency and quality services of the healthcare system for people with disabilities is directly related to the orientation of health workers to people with disabilities, the attention to the matter is not sufficient (Rogers et al., 2016; Kritsotakis et al., 2017; Kirshblum et al., 2020).

This discussion allows identifying the currently existing discrepancies between:1) expectations that people with disabilities should receive equal and high-quality healthcare services; 2) the minimal focus in the documents regulating the training of health workers on this aspect governing the affairs in the healthcare system; 3) issues faced by health workers working with people with disabilities established through research; and 4) the call of the World Health Organisation of the United Nations to improve the specialist training in a way that would enable the healthcare system to cater better to people with disabilities. These contradictions encourage a closer look at the education of health workers and raise a question how to enhance it, so that health workers who have graduated from the schools of higher education would be able to work more effectively with people with disabilities, thereby reflecting the disabled people’s needs. Finding the answer to this strategic question is multi-faceted and nuanced. The focus in this article will fall on the following exploration: how future health workers (students of schools of higher education) understand their professional work with people with disabilities. Such understanding is the result of training of health workers; therefore, its analysis allows outlining the problems related to the education of healthcare education focused on the work with people with disabilities, and shaping guidelines how to foster it.

This chapter explores the understanding of the future health workers about their future professional work with people with disabilities. The collage technique was used as the main method to obtain, collect and interpret the data. The research was carried out while adhering to the attitude of social constructivism claiming that a human being is an entity looking for and creating the meaning (Crotty, 1998). Lock and Strong (2010) describe the creation of meanings from the social constructivism perspective as “ways of meaning-making, being inherently embedded in socio-cultural processes, are specific to particular times and places. Thus, the meanings of particular events, and our ways of understanding them, vary over different situations” (p. 7). In the context of this article, an important aspect is that of the professional understanding of work related to the professional identity. Professional identity basically defines the identification of an individual with a certain group doing the same job (Hendrikx & van Gestel, 2017). Yet it encompasses two key elements: interpersonal (consisting of culture, knowledge, values, and beliefs) and intrapersonal (self-perception of an individual in the context of the profession represented) (Sutherland & Markauskaitė, 2012). Professional identity affects the employee attitude and behaviour in their work activities (Sutherland & Markauskaitė, 2012; Caza & Creary, 2016); therefore, it is highly important what professional identity the employees are cultivating. Professional identity is dynamic, socially-constructed, constantly changing, depending on what is told, how, and in what way (Pöyhönen, 2004). It is an individual construct (Bridges, Macklin, & Trede, 2012), formulated in social interactions (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2011). The social constructivist approach to the formation of professional identity has emphasised the role of student training in this process, because professional training is an important factor constructing the professional identity (Luyckx, Duriez, Klimstra, & De White, 2010; Bridges, Macklin, & Trede, 2012; Sutherland & Markauskaitė, 2012; Caza & Creary, 2016).

In the most general sense, the collage is defined as a piece of art made by pasting together various different materials and images (Butler-Kisber & Poldma, 2010). According to Bressler (2006), “the arts provide rich and powerful models for perception, conceptualization, and engagement for both the makers and in viewers” (Bressler, 2006, p. 52). Creation of a collage could include various materials or things from the material world (newspapers, magazines, drawings, texts, textile, pencils, beads, etc.). Materials to be used most commonly include clippings of photos and pictures from various sources, by composing them in any way chosen by the author by ascribing connotative meaning to all of them. When collating poorly related images, the effect of incompatibility arises, and their composition conveys the conceptualised idea of the collage (Plakoyiannaki & Stavraki, 2018).

On the other hand, collage is an acknowledged research method used to reveal thoughts and experiences of research participants, understand their individual experience, analyse the meanings of concepts and ideas perceived by persons or groups thereof, and show various interpretations of social problems (Reissman, 1993). Collage as an arts-based research method allows the participants and researchers to link the “ideas in a non-linear way that brings a deeper understanding of a given phenomenon” (Kay, 2008, p. 147). Each image chosen for a collage evokes associations, memories and feelings, and also helps to connect personal experience with the existing values and attitudes. Not only the choice of individual images, but also their composition into one image too helps seeing multiple meanings of objects and phenomena as well as connections between them, thereby generating the conceptual idea of the collage. Such a study based on visual information eases the verbal communication and helps to reveal meanings and experiences that are difficult to put into words. Therefore, such a collage technique is seen as a valuable means to enter the inner world of a person (Kay, 2013).

The application of the collage technique does not require a large scope of the research sample because the aim is not to reach the conclusion applicable to the greater part of the population (Davis, 2008; Butler-Kisber & Poldma 2010; Plakoyiannaki & Stavraki, 2018). The research respondents were drawn from the pool of volunteers from the higher courses of study programmes that train health workers. All of them received an email specifying the purpose of the research, introducing the research method, while also presenting all other information related to the issue researched and the implementation of the study itself. 5 students from Physiotherapy and Radiology study programmes volunteered to participate in the project.

A collage was created in the group, and the students were allowed to choose with whom they want to work. The groups were divided based on their specialities: 3 physiotherapists (Group 1) and radiologists (Group 2). All the participants signed the letter of consent, confirming that they allow using this material for research purposes. They were ensured that no personal or otherwise identifying information would be revealed either when analysing the data or when introducing and disseminating the research results.

None of the students had an experience of making a collage before. This fact should not be treated as a limitation of the research. Participation in such research studies does not require previous artistic experience, because “arts-based research is not only for professional artists and arts educators. With <...> training, education, practice, and dedication <...> anyone might become a skilled arts based researcher” (Barrone & Eisner, 2011, p. 167). Those who participate in artistic practices for the first time can experiment with different materials and create a collage as meaningful as those who do have artistic experience. Rather than creating a work of art, in this case, a more important point is the opportunity to show one’s unique approach to the problem, reveal one’s relation with other people and the world, and position oneself in the professional field (Lock & Strong, 2010).

Creation of the collage, both in the group and individually, is based on 5-stage steps (Davis, 2008; Butler-Kisber & Poldma 2010; Plakoyiannaki & Stavraki, 2018). In our case, the research was carried out in the following order:

1. Formulation of the problem and introduction of a task. Before introducing the task, both research groups were equipped with the necessary materials: scissors, glue, 3 magazines with colourful pictures, and 50 pictures from other sources. Among them, there were 20 pictures printed as results of online search of the keywords pertaining to people with disabilities, healthcare system, and health programme. This helps ensure the diversity and abundance of pictures, thereby allowing the participants to choose the images that would help to convey their understanding about the notion of work with people with disabilities. Students received the following task:

Create a collage that would answer the question: How do you understand the purpose of your future profession working with people with disabilities. I suggest choosing images that would seem to you related to the said question. Please discuss in the group which one of them you will choose and how you will place them on the sheet of paper. You can use coloured markers to show connections between the images, emphasise what is important to you in the picture or a part thereof, write down the text. Use at least 15 pictures and photos. Glue the images on an A2 or A3 paper sheet. This collage is a part of a research project, so, after it has been finished, I will make a group interview.

2. Creation of the collage. First of all, each research participant chose pictures he or she found meaningful and related to the subject of the research study. Later on, these images were discussed in the group, so that to decide which of them should be used to create one collage, how and why should they be composed together. There were no time limitations to create the collage, but both groups finished their work within half an hour.

3. Introduction of the collage. The students of both groups introduced their collage by submitting an abstracted idea, explaining why they chose those images, why they were composed the way they were, why graphic figures were used (lines, arrows, symbols), and what they were intended to mean. The research participants could select individual or group presentation. In both cases, the collage was introduced by one student, while the remaining group members provided additional explanation(s).

4. A conversation between the researcher and the research participants. Visuals used in the collage were used to develop the dialogue. Students were asked why they chose these particular pictures, what was their meaning and connection to the existing experience, why they were placed in one place or another, what the emotional expressions of people in the images would mean, etc.

5. The final discussion, during which, it was explained how the collage was created, what were the roles of group members, what were the processes of the dialogue and communication and other experiences of this creative process.

The conversations of the research participants during the creation process of the collage, the introduction of the works and the final discussion were recorded and transcribed. The total length of the recording was ca. 2 hours. The research transcript consisted of 28450 words.

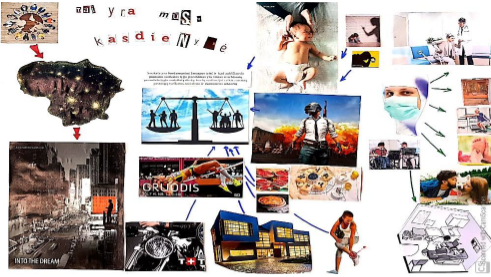

The creation of the first collage made by 3 students of the physiotherapy study programme included 24 pictures. Connections were revealed through 12 arrows. Even though there was no task given to name the work, the students used letters to spell the name reflecting the idea of the collage This is our Everyday Life (Fig. 1).

The collage has a clear three-part structure: a contextual place for work for people with disabilities (3 images), causes of disabilities (8 images), and activities of health workers (7 images). The students introduced their collage in the following way:

This is us from the world, this is the world, this is Lithuania... We have chosen these pictures from where we got this disability. This includes the arrival of a child to the world, not like we expected him to be, as he has a disability. There are various catastrophes, our life is dangerous. Certainly, professional sports and our very comfortable life that contains a lot of risk factors, constant rush, and desire to be in time. Also, nutrition and various injuries... This is everything we can do to integrate people. That it is possible to lead a full life with disability and psychological problems.

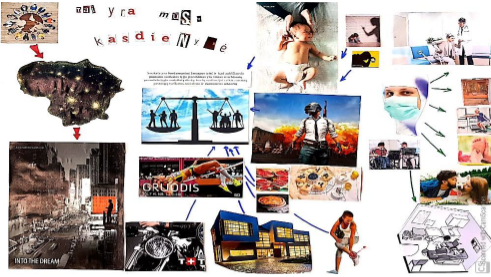

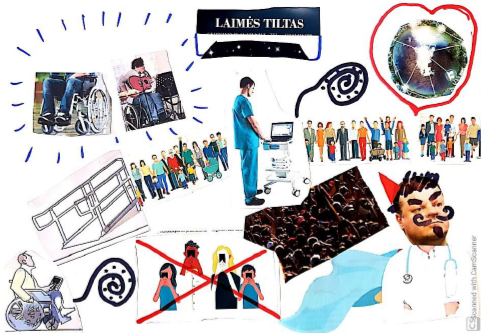

The second collage was created by the students of radiology. To make the collage, the research participants used 15 pictures. Also, as in the case of the first collage, connections were drawn with colourful markers, and symbols were used to emphasise the thought expressed. Even though only five symbols were used, the meanings conveyed through them is more varied: heart (love), dashes in a circle (attention, shining), crossing lines (an unsuitable approach), a dot-decorated twist (related to other images). The picture is called The Bridge of Happiness (Fig. 2).

The second collage is also divided into three distinctive parts: people with disabilities (3 images), the attitude of the society to people with disabilities (5 images), political and geographical (local) context of the problem (3 images). The students described the collage briefly:

Here we have people with disabilities... The attitude of the society and specialists towards such a person is very important. A lot of people are limited to their own lives. If we were united, things would be different... It takes to change the attitude of the society, the healthcare system should be put into order. Politicians, unfortunately, have not done a lot in this area.

Before analysing the data, similarities between the projects can be observed: both collages have names, a clearly visible three-part composition of the collage, and symbols used to reveal connections and meanings in the picture. Even though, in the second case, there are fewer pictures, the narrative based on them is outspoken, revealing the notion of work of people with disabilities.

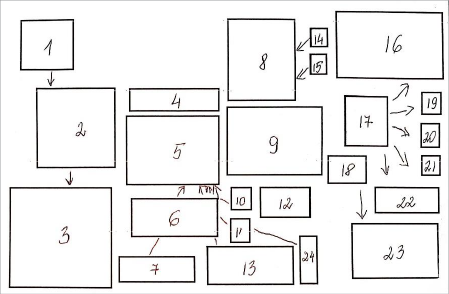

It is possible to analyse the collage data in a variety of ways, i.e., by using semiotic, compositional, discourse and psychoanalytic analysis of the content (Plakoyiannaki & Stavraki, 2018). In this research study, content analysis was used to analyse the data, and focusing on identification and interpretation of images was used for the collage (Mannay, 2010; Butler-Kisber & Poldma, 2010). Data preparation for analysis involved a two-stage strategy (Van Schalkwyk, 2010). First of all, all pictures in the collage were numbered, thereby making their schematic picture (see Fig. 3).

In stage two, the analysis of the picture descriptions took place, looking for a way to understand the meanings ascribed to the images. There was a story grid created for each collage, thus revealing the unity of insights and explanations provided (Table 1). The denotation inventory features all images used in the collages, whereas the connotation section lists the meanings of images provided by the research participants, while the third section features the descriptions of images chosen.

|

No. |

Denotational inventory |

Connotations |

Description of the image in relation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The main aspect of collage analysis is reliability assurance, because the analytical process of both visual and textual information is inevitably subjective (Golafshani, 2003). When analysing the collage and its story, the researcher had to be critical, constantly get back to the original collage and interpretations of the visuals used, and also check the adequacy of the visual connotations. To ensure reliability, it is recommended to also employ other researchers and ask them to evaluate their collected data and interpretation thereof. In the context of this research, the primary data analysis was carried out by the first researcher. Other researchers shared their insights and evaluation of the primary data analysis. The research results are introduced after all of the authors have agreed on the suitability of data interpretation. The primary data analysis was introduced to the students participating in the research, with the question whether data interpretation matches what they have expressed in the collage regarding the notion of work with people with disabilities, while also asking to add if something was still left unsaid or happened to be not yet included into the research report. The research participants did not provide any additional arguments or comments.

The research data analysis includes the collages by two groups, their introduction transcripts, and the field notes of the researchers. Analysis of the research study has helped to identify two topics: the contextuality of professional activity, and the professional agency.

In the literature on professional development, sensitivity to the contexts of professional activity is called contextual intelligence (Blackmore, Chambers, Huxley, & Thackwray, 2010). The notion ‘concept’ is used to define the time, spatial, social and ideological attitudes, political systems and boundaries of certain disciplines or areas (Mathieson, 2012; Leibowitz, Vorster, & Clever, 2016). Composing the elements chosen in one piece together, students generated the idea of the collage, even by giving a metaphorical name to the work. It has been noted that the names of collages and narratives defining them have a contextual meaning. When considering their future professional work with people with disabilities, students paid attention to the geographical (local), social and political contexts.

The story introducing the first collage features the experience with the future profession, and considers its purpose in the context in the place of residence, country and the world (images 1 to 3). Students also described the space of the professional activity from the spatial aspect:

This is us from the world, this is the world, this is Lithuania. And here we are in our existence – the city, at home, on the streets. It is all connected, because we live in a global world. In any part of the Earth, we face the problems of people with disabilities.

In the second collage, only one image is dedicated to contexts naming the location, but it is circled in a red line symbolising the heart. Students see the following meaning of the Earth image with the symbolic circling:

We are all the inhabitants of the same planet, everyone needs to be respected. Love, respect for other forms of life, attention for people with disabilities should be the norm. It is not only a problem of you or me. It is all about us all.

Therefore, in both cases, work with people with disabilities is perceived globally, i.e., not only from the perspective of the place of residence. The opinion was expressed that, in any part of the world, there are people with disabilities, and they need the attention of health workers. Putting the emphasis on the importance of love, respect, attention to people with disabilities, students expressed the idea of the global unity: “We are the residents of the same planet.”

The social context is revealed by discussing the unfavourable approach of society towards people with disabilities along with the cause of disability. The image of scales chosen (the first collage, picture 5), according to students, is the best illustration of the situation that there is “no equality between the healthy people and the people with disabilities.” The authors of the second collage also pay a lot of attention to the negative attitude of society towards people with disabilities (there are five images dedicated to that). The emphasis is placed on the inability to react, lack of knowledge how to behave with people with disabilities. When describing the picture of people with cell phones, respondents tell the following:

A lot of people are confined to their own lives, living them inside their phones and not trying to understand... The society is very clearly afraid of these people [with disabilities]... Sometimes, a person does not have a leg, an arm, or has one physical alteration or another. He or she is perceived as a monster rather than a person. People are afraid of them. Various seizures happen for people with disabilities, and others do not know how to help them at all. We don’t know how to live next to the people with disabilities.

This imaginative part of the collage along with the student commentary have revealed the social context of intolerance to disability: ‘the healthy ones’ are afraid of people with disabilities, avoid them, and cannot co-live with them.

In their collages, students associate the origins of disability with the flawed way of life, poorly assessed risks, congenital disease (Collage 1, images 4 to 15). The comment by students: “The risk of becoming disabled lurks around each corner” as well as the name of the first collage This is our Everyday Life reveals the understanding that disability is a natural part of our lives: it can be congenital, or gained later in life. According to the research participants, people live in an unsafe world, and becoming disabled is possible because of risky activities, malnutrition, or doing sports. The factor of coincidence, ‘circumstances’ is also accepted, when the disability is developed because of conditions which do not depend on the people subjected to them.

The political context of the future profession can be conveyed by a discourse of Group 2 while creating the collage:

– Oh, I will cut out Skvernelis [the Prime Minister]. He screwed up with a lot of things.

– Oh, I also need Veryga [the Minister of Health of the Republic of Lithuania]. Since the work of healthcare institutions is atrocious.

– Everything starts from political decisions.

– It not only starts, but also ends.

– Draw moustache on Skvernelis, make him look grumpy...

– I will also add this hat, so he would be funny.

This dialogue, exchanged by students, pays attention to the political context of professional activities, and discusses the mentioning of specific politicians and their actions, while observing the influence of the political solutions to the quality of the healthcare system. Students also express their opinion about the said politicians by adding the moustache (“let’s make him grumpy”), adding a hat (“to make him funny”). Unexpected insights come from the parallels drawn from the images of the politician and the superman (collage No. 2, images 14 and 15). When asked to explain the meaning of these pictures, the students replied with laughter: “the Prime Minister should be a superman, but it is not the case. And, in general, it is not funny.” The elements of the collage as well as the excerpts of interviews and conversations reveal a negative evaluation of the national healthcare policy context. Politicians are treated as incompetent (“he screwed up with a lot of things”), angry (“let’s make him look grumpy”), and are deemed to be making wrong decisions. Therefore, according to the students, the situation of healthcare institutions is a complicated one.

The topic of the professional agency arose after the evaluation of the number of images related to the professional activities and their descriptions provided. Schlosser (2019) states that, in the broadest sense, the agency is simply a being with the ability to act, and, therefore, agency can be found in virtually any place. Bandura (2006) assigns four core properties which define the personal agency: intentionality, forethought, self-reactiveness, and self-reflectiveness. Intentionality refers to making plans and creating strategies, forethought comprises mental actions that plan further ahead, and includes the projection results in the future, self-reactiveness describes the step from plans and aspirations to the actual realization of one’s intentions when one regulates the course of action according to one’s judgement. Finally, self-reflectiveness covers the criticism of one’s functioning through an awareness and evaluation of one’s thoughts and actions. Only the first one of the list by Bandura (2006) would find the traits of agency – intentionality – it was observed when analysing collages and their narratives. Even when asked about what should be changed in the healthcare system, students did not make a connection between them and their professional activities, nor did they strive to plan their future actions and project their results for the future, and envisage steps from the plans to the implementation of intentions.

Even though the research participants were asked to depict the purpose of their future profession working with people with disabilities, the authors of the first collage directly addressed their profession (physiotherapy), only three out of twenty-four pictures were used, while the creators of the second collage (radiologists) only used one out of fifteen. In the first case, it spoke about health workers in general, in which case, the purpose of their occupation is presented as the third (last) structural component of the collage. The students ground their logic of the composition in the following way:

It is just the way it is that looking for help comes last. We live, work, practise sports and do crazy things. And then we need doctors. We do crazy things in our daily lives and only then look what the outcomes are.

Such positioning of the profession, where priority belongs to the social and political contexts, shows the notion of the future occupation as depending on the circumstances. Health workers are perceived as persons who face the outcomes of certain actions, who solve the problems of acquired or congenital disability within the regulated framework of their professional activity: “we do what we are supposed to do.” Actions that could be done wanting to change the situation are formulated in an abstract way, without naming specific people or institutions, not seeing oneself as active participants of changing the process: “The attitude of the public to the healthcare system needs to change, it must be managed better.” “The society could be more responsible in contributing to the better conditions”; “It would be great if the society paid more attention to that problem.”

Only a couple of insights recorded reveal the aspiration of the students to make plans and create strategies that would contribute to the solution of the problems faced by people with disabilities:

• Adaptation of the physical environment: “It is so inconvenient in most places for people with disabilities to enter, there are no conditions to reach the desired place”;

• Elimination of bureaucratic obstacles, because “people with disabilities must go through a lot of instances to received help”;

• Changing the attitude of the society towards the disabled: “We need a more real vision and personal take on the problems. More events to meet people with disabilities, more affairs to share with them”;

• Psychological training for health workers to work with people with disabilities: “A person must be prepared so as not to get scared. It takes to know how to gain one’s trust”;

• Strengthening the public focus and activism on solving problems: “If we were united, things would be different... Just like protests in the USA... They are not afraid of speaking out and expressing [themselves]”.

The metaphorical name of the second collage, The Bridge of Happiness, can be mentioned as an example of agency. At the centre of the composition, there stands a healthcare worker who, according to the research participants, is the most important person who can solve the problem of people with disabilities: “There is a bridge needed that would help the integration of people with disabilities. At the centre of the bridge, there is a person, with the profession the purpose of which is to help doing so.” Even though it is the only image related to the future profession of students (Radiology), its place in the composition of the collage and explanation of its meaning shows an active and engaged relationship with the future profession.

Collages about the project created by research participants in relation to their work with people with disabilities, narratives about the collages, interviews and interaction material have allowed identifying some important aspects related to the work of future health workers in their dealings with people with disabilities.

In both groups that have participated in this study, geographical contextuality of a health worker’s work with people with disabilities have been brought up – the research participants understand that, in every corner of the world, there are people with disabilities, and they have equal rights just like the other people to receive high quality healthcare services. This approach reflects global, European and national attitudes towards the health and disability: taking care of people with disabilities is a public problem (WHO, 2015; The Law on Social Integration of the Disabled, 2004), and that all countries must ensure that such people must be provided with the same quality of healthcare services just like other people, thereby preventing any manifestation of discrimination in this area (UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006).

The collages, supported with the student commentary, helped revealing their understanding about the social context of working with people with disabilities. This context is perceived as intolerance to disability, there is no equality between the healthy ones and people with disability, the latter ones are feared, even by evoking disgust, avoided, and failure to co-live is being felt. Siebers (2008) explains this social context with the fact that, for a long time in our society, disability was being perceived as simply a medical term, in which case, disability was related only to medical services and frequently related to death, disease or injury, which, in itself, determined the stigmatization of people with disability in the society. Taking into consideration the problem of the social context brought up by students during the study as intolerance to disability, it raises the concern of a risk that the future healthcare employees will be affected by the very same negative social context they are talking about. Such concerns occur when bearing in mind the research of Santoroa et al. (2017) and Kritsotakis et al. (2017), claiming that newly trained health workers and students usually are affected by negative and stereotypical attitudes about people with disabilities, which, in their turn, have a negative effect on their communication, and which prevents the provision of quality and equal-level services. Therefore, this trend was made obvious during the research study, and it also allows to assume that there are certain signals that, despite generalising the problems of the social context, students have not limited themselves entirely from it.

Another aspect that was made clear during the research is that the way one becomes disabled is interpreted reveals a multi-layered perception of students about the manifestation of the disability: according to them, disability can be acquired or congenital, a lot of dangers and poor choices leading to disability lurk for a person in life. Such understanding partially matches the existing attitude declared by the World Health Organisation (2015) that disability is not simply a social or biological phenomenon, but rather a public problem of our society’s health caused by a variety of factors starting from certain inherent or acquired trauma, ending with the speed of the progress of medicine and advancements in the diagnostics of diseases. However, it should be considered that, recently, a significant shift in the treatment of people with disabilities has emerged, in which the movement from the narrow medical approach to a wider perception of disability and rejection of seeing disability as a negative outcome can be observed (Siebers, 2008). A wider approach to disability expressed by the study participants allows identifying a wide approach of the participating future students healthcare workers, but still, however, the medical approach has not abandoned its earlier position yet.

The research study has revealed that students participating in it have a rather negative opinion about the political aspect of their work with people with disabilities and are angered by politicians, who, according to them, behave in an arrogant and non-professional manner. They have formed an opinion that, because of the fault of the politicians, the healthcare system functions insufficiently in terms of quality, and it also does not assure the proper provision of healthcare services for people with disability. Even though it has been accepted that some political decisions have been made, they are not being sufficiently implemented in practice and often remain on the level of merely political declarations. Such understanding about the political context of the work of future health workers with people with disabilities only partially mirrors the actual situation. In fact, the Public Audit (National Audit Office of the Republic of Lithuania, 2018) admitted that, on the political level, there have been a lot of decisions made in Lithuania because of which the situation of people with disabilities in the healthcare system has been improving, but the equal rights of disabled individuals to the services provided by the healthcare system are not completely ensured yet. However, it is worth mentioning that such a situation is not prevalent exclusively in Lithuania. According to the research by the aforementioned Rogers et al. (2016), Kritsotakis et al. (2017), and Kirshblum et al. (2020), in other countries, in this case, specifically, the USA and Greece, irrespective of a lot of talks about striving to ensure the equal rights of people with disabilities to receive the same quality of healthcare services, there are a lot of problems observed in the healthcare systems because of which they are not functioning properly or efficiently. Various communications and reports by the World Health Organisation (2011, 2015, 2016) reveal that the problems of people with disabilities are not only the national problem of individual countries, but rather a challenge which demands the global attention. However, it is also noteworthy that international initiatives are undertaken like the public declaration adopted by the World Health Organisation (2016), outlining the strategy to move towards the universal healthcare by 2030, which states that people with disabilities should have their rights assured in the healthcare system, whereas international agreements (e.g., United Nations (2006) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities) show that the proper assurance of rights of people with disabilities in the healthcare system is the general position of the entire world. Equally, each country individually is obligated to improve the situation of people with disabilities in the healthcare system and ensure service approachability based on all of these international agreements. Keeping the said facts in mind, the understanding of student respondents about the political context and regulations of their work with people with disabilities seems too limited and narrow.

This research study has helped to identify the problem of agency of health workers in the healthcare system. Even though, in the concept of working with people with disabilities, the health workers are given the main role, yet the collages, the narratives about them, and the discourses creating them as well as the interview say nothing about the implementation of those roles, the perception of professional functions, as well as forethought, self-reactiveness, self-reflectiveness, which, according to Bandura (2006), defines the personal agency. Even internationality, which is one of the key components of personal agency, is expressed very weakly. The students participating in the research do not seem to have a vision about their professional activities with people with disabilities, and they tend to pass the responsibility for a better position of people with disabilities in the healthcare system to other actors: politicians, representatives of other professions, and other institutions. Such understanding of the students regarding their future work with people with disabilities shows what professional identities students construct in the institutions of higher education. Keeping in mind that the professional identity affects the professional activities (Sutherland & Markauskaitė, 2012; Caza & Creary, 2016), it is of utmost importance for the education of health workers to have enough time allotted to train future specialists for work with people with disabilities, thus shaping the professional identity of health workers capable of working with people with disabilities. Therefore, the accessibility of the healthcare system and the quality of services for people with disabilities would have to be first and foremost focused on adequate, knowledge- and professional identity education-based training of health workers to work with people with disabilities: to ensure that the legal basis that regulates the specialist training to work takes into consideration the preparation to work with people with disabilities, as well as for general analysis to the current situation with the objective to look for proper ways to solve the problems involved.

Having taken a closer look at the education of health workers and focusing on how the future health workers (students of institutions of higher education) understand their professional work with people with disabilities, and by having conducted a research study based on a collage technique to find out this in detail, it is possible to conclude that there are underlying problems in the training of future health workers revealed from the perception of the research participants about their future professional activities when working with people with disabilities. These perceptions reveal partially limited perception of professional activity contexts, poor agency, and, as a result, such trends of shaping the professional identity that would programme the future problems of people with disabilities dealing with the healthcare system. To some extent, it might be related to the national legal base regulating the education of health workers, especially with the descriptions of the field of studies, on the basis of which, health workers are trained, and in which the focus on the work with people with disabilities is minimal. Institutions of higher education training health workers subscribing to such descriptions only in a limited way help the students gain a modern approach to the phenomenon of disability, its causes, context, the legal basis of work with people with disabilities, while educating about their professional conduct when working with people with disabilities. It does not facilitate their process of understanding personal responsibility and strengthening their personal agency.

An aspect that can be treated as a limitation is the fact that the research study relied on the data collected from 5 students from one university, and only two collages were created. However, analysis of the collages has revealed that, irrespective of this fact, there have been problems with the education of health workers which are thus made evident, and the research which has been conducted enables looking for the ways and finding how to foster the preparation of future health workers to work with people with disabilities. And even if only some students face the problems identified, it does not reduce the significance of the study, because these students will potentially work as health workers and initiate this work in the healthcare system with the approach that would be out of date with the period of time and public expectations.

The article has raised a question how to consolidate the education of future health specialists so that, after graduation, they would be able to work more efficiently with people with disabilities and meet their needs. The research results suggest that it would be meaningful to prepare the national concept for the training of health workers to work with people with disabilities, while taking into consideration the recommendations by the World Health Organisation, the United Nations, the European Commission, and scientific research. The concept should also be considered when it is needed to edit descriptions of medicine and health study programmes in order for them to direct the efforts of institutions of higher education to improve the training of health workers so that they could understand the purpose of their profession in terms of working with people with disabilities, and so that they would have clearer visions of the future about their work; as a result, the students would construct their professional identities, which, in turn, would help them in the professional activities to ensure equal rights for people with disabilities to receive high-quality healthcare services. When preparing the aforementioned documents, it would be useful to carry out more research regarding the education of future health workers.

References

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 164–180.

Barone, T., & Eisner, E.W. (2011). Arts based research. SAGE Publications.

Blackmore, P., J. Chambers, L. Huxley, & Thackwray, B. (2010). Tribalism and territoriality in the staff and educational development world. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 34(1), 105–117.

Bresler, L. (2006). Toward connectedness: Aesthetically based research. Studies in Art Education, 48(1), 52-69.

Bridges, D., Macklin, R., & Trede, F. (2012). Professional identity development: A review of the higher education literature. Studies in Higher Education, 37(3), 365-320.

Butler-Kisber, L., & Poldma, T. (2010). The power of visual approaches in qualitative inquiry: The use of collage making and concept mapping in experiential research. Journal of Research Practice (6)2, 1-16.

Caza, B. B., & Creary, S. J. (2016). The Construction of Professional Identity. In A. Wilkinson, D. Hislop, & C. Coupland (Eds.), Perspectives on contemporary professional work: Challenges and experiences (pp.259-285). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research. SAGE Publications.

Davis, D. (2008). Collage inquiry: Creative and particular applications. LEARNing Landscapes, 2(1), 245–65.

European Comission. (2015). The European Commission supports research and innovation on technologies to break down barriers for people with disabilities. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/european-commission-supports-research-and-innovation-technologies-break-down-barriers-people

Golafshani, N. (2003). Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 8(4), 597-607.

Hendrikx, W., & van Gestel, N. (2017). The emergence of hybrid professional roles: GPs and secondary school teachers in a context of public sector reform. Public Management Review, 19(8), 1105-1123.

Kay, L. (2008). Art education pedagogy and practice with adolescent students at-risk in alternative high schools. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Northern Illinois University, Dekalb, IL

Kay, l. (2013). Bead collage: An arts-based research method. IJEA, 14(3), 1-19.

Kirshblum, S., Murray, R., Potpally, N., Foye, P. M., Dyson-Hudson, T., & DallaPiazza, M. (2020). An introductory educational session improves medical student knowledge and comfort levels in caring for patients with physical disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 13, 1-6.

Kritsotakis, G., Galanis, P., Papastefanakis, E., Meidani, F., Philalithis, A. E., Kalokairinou, A., & Sourtzi, P. (2017). Attitudes towards people with physical or intellectual disabilities among nursing, social work and medical students. Journal of Clinical Noursing, 26(23-24), 4951- 4964.

Leibowitz, B., Vorster, J. A., & Clever, N. (2016). Why a contextual approach to professioal development? South African Journal of Higher Education, 30, 1-7.

Lietuvos Respublikos neįgaliųjų socialinės integracijos įstatymas [Law of the Republic of Lithuania on the Social Integration of the Disabled] (1991). Lietuvos aidas, 1991-12-13, No. 249-0.

Lietuvos Respublikos socialinės apsaugos ir darbo ministerija [The Ministry of Social Security and Labour of the Republic of Lithuania] (2019). Neįgaliųjų socialinė integracija. Statistika. Retrieved from https://socmin.lrv.lt/lt/veiklos-sritys/socialine-integracija/neigaliuju-socialine-integracija/statistika-2

Lietuvos Respublikos sveikatos sistemos įstatymas [Law on the Health System] (1994). Valstybės žinios, 1994-08-17, No. 63-1231. Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/TAR.E2B2957B9182/asr

Lietuvos Respublikos švietimo ir mokslo ministro įsakymas dėl Bendrųjų studijų vykdymo reikalavimų aprašo patvirtinimo [the Decree of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania “On the Approval of the General Requirements for Study Programmes”] (2016). TAR, 2016-12-30, No. 30192. Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/739065a0ce9911e69e09f35d37acd719

Lietuvos Respublikos švietimo ir mokslo ministro įsakymas dėl Laipsnį suteikiančių pirmosios pakopos ir vientisųjų studijų programų bendrųjų reikalavimų aprašo patvirtinimo [Decree of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania “On the Approval of the Description of General Requirements for Degree-Awarding First Cycle and Integrated Study Programs”] (2010). Valstybės žinios, 2010-04-17, No. 44-2139. Retrieved from https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.369937

Lietuvos Respublikos švietimo ir mokslo ministro įsakymas dėl Magistrantūros studijų programų bendrųjų reikalavimų aprašo patvirtinimo [Decree of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania “On the Description of General Requirements for the Master’s Study Programs”] (2010). Valstybės žinios, 2010-06-10, No. 67-3375. Retrieved from https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.374821

Lietuvos Respublikos švietimo ir mokslo ministro įsakymas dėl Medicinos studijų krypties aprašo patvirtinimo [The Decree of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania “On the Approval of the Description of Medicine Field of Studies”] (2015). TAR, 2015-07-23, No. 11577. Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/6f8141b0311e11e5b1be8e104a145478

Lietuvos Respublikos švietimo ir mokslo ministro įsakymas dėl Reabilitacijos studijų krypties aprašo patvirtinimo [The Decree of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania “On the Approval of the Description of Rehabilitation Field of Studies”] (2015). TAR, 2015-07-23, No. 11578. Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/89240fd0311e11e5b1be8e104a145478

Lietuvos Respublikos švietimo ir mokslo ministro įsakymas dėl Slaugos studijų krypties aprašo patvirtinimo [The Decree of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania “On the Approval of the Description of Nursing Field of Studies”] (2015). TAR, 2015-07-23, No. 11582. Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/f832b200311e11e5b1be8e104a145478

Lietuvos Respublikos švietimo ir mokslo ministro įsakymas dėl studijų kryptis sudarančių šakų sąrašo patvirtinimo [The State Audit Office of the Republic of Lithuania] (2010). Valstybės žinios, 2010-02-23, No. 22-1054. Retrieved from https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.365785.

Lietuvos Respublikos Valstybės kontrolė [The State Audit Office of the Republic of Lithuania] (2018). Valstybinio audito ataskaita. Asmens sveikatos priežiūros paslaugų kokybė: saugumas ir veiksmingumas. Retrieved from https://www.vkontrole.lt/pranesimas_spaudai.aspx?id=24629

Lock, A., & Strong, T. (2010). Social constructionism: Sources and stirrings in theory and practice. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Luyckx, K., Duriez, B., Klimstra, T. A., & De Witte, H. (2010). Identity statuses in young adult employees: Prospective relations with work engagement and burnout. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77, 339–349.

Mannay, D. (2010). Making the familiar strange: Can visual research methods render the familiar setting more perceptible? Qualitative Research, 10(1), 91–111.

Mathieson, S. (2012). Disciplinary cultures of teaching and learning as socially situated practice: rethinking the space between social constructivism and epistemological essentialism from the South African Experience. Higher Education, 63, 549‒564.

Plakoyiannaki, E., & Stavraki, G. (2018). Collage Visual Data: Pathways to Data Analysis. In C. Cassell, A.L. Cunliffe, & G. Grandy (Eds), The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods (Vol.2, pp. 313-328). SAGE Publications.

Pöyhönen, A. (2004). Modeling and measuring organizational knowledge capacity. Acta Universities Lappeanrantaensis, 51, 76-98.

Riesman, C. K. (1993). Narrative analysis. Sage.

Rogers, J. M., Morris, M. A., Hook, C., & Havyer, R. D. (2016). Introduction to disability and health for preclinical medical students: Didactic and disability panel discussion. MedEdPORTAL, 12, 10429.

Santoroa, J. D., Yedlab, M., Lazzareschic, D. V., & Whitgobd, E. E. (2017). Disability in US medical education: Disparities, programmes and future directions. Health Education Journal, 76(6), 753-759.

Sarmiento, C., Miller, S. R., Chang, E., Zazove, P., & Kumagai, A. K. (2016). From impairment to empowerment: A longitudinal medical school curriculum on disabilities. Academic Medicine. Journal of Association of American Medical Colleges, 91(7), 954-957.

Schlosser, M. (Winter 2019 Edition). Agency. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/agency/.

Siebers, T. (2008). Disability theory. The University of Michigan Press.

Skorikov, V. B., & Vondracek, F. W. (2011). Occupational identity. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 693-714). Springer.

Studijų kokybės vertinimo centras (2015). Laukiame pasiūlymų dėl studijas reglamentuojančių aprašų sistemos plėtros. Retrieved from http://www.skvc.lt/default/lt/naujienos/pranesimai/laukiame-pasiulymu-del-studijas-reglamentuojanciu-aprasu-sistemos-pletros.

Studijų kokybės vertinimo centras (2018). Tobulinama studijas reglamentuojančių aprašų sistema. Retrieved from http://www.skvc.lt/lt/naujienos/pranesimai/tobulinama-studijas-reglamentuojanciu-aprasu-sistema.

Sutherland, L., & Markauskaite, L. (2012). Examining the role of authenticity in supporting the development of professional identity: An example from teacher education. Higher Education, 64(6), 747-766.

United Nations (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Retrieved from

United Nations (n. d.). Toolkit on disability for Africa. Inclusive health services for persons with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/disability/Toolkit/Inclusive-Health.pdf.

van Schalkwyk, G. J. (2010). Collage Life Story Elicitation Technique: A Representational Technique for Scaffolding Autobiographical Memories. The Qualitative Report, 15(3), 675-695.

World Health Organization (2011). World Report on Disability. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report/en/.

World Health Organization (2015). WHO global disability action plan 2014-2021. Better health for all people with disability. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/199544/9789241509619_eng.pdf;jsessionid=DD0055EEC51D278E6A7215891FBFF5BF?sequence=1.

World Health Organization (2016). Working for health and growth: investing in the health workforce. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250047/9789241511308-eng.pdf;jsessionid=8DFCDAE1FE4504D5B499011574113FB3?sequence=1.