Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2022, vol. 49, pp. 83–97 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2022.49.6

Mārtiņš Driksna

University of Latvia

mdriksna@edu.riga.lv

Baiba Kaļķe

University of Latvia

baiba.kalke@lu.lv

Abstract. This study examined competences of heads of schools when acquiring the current terminology of education in Latvia. In the school year 2020/2021 schools in Latvia implemented new approach to learning by introducing the curriculum reform called “Introducing the competence approach in the instructional content “Skola 2030”. The event led to several changes in the curriculum as well as an addition of various new terms to be used when introducing the reform to schools; therefore, to successfully implement the reform heads of schools have to fully understand the new curriculum and terms. The aim of this research paper was to study what the necessary competences of heads of schools are when acquiring the current terminology of education.

To achieve the objective, analysis of theoretical literature, scientific research and statistics were performed; a survey for heads of schools was developed and conducted; the results of the study were compiled.

In the empirical part it was clarified which were the necessary competences of heads of schools that related to acquiring, using, and passing on the terminology of education.

The study found that in the acquisition of the current education terminology the most important competences are social competence, methodological competence, self-competence and their subcompetences.

Keywords: education, heads of schools, terminology of education, competences in the terminology of education.

Santrauka. Straipsnyje nagrinėjamos mokyklų vadovų kompetencijos jiems pratinantis prie naujos Latvijoje priimtos ugdymo srities terminijos. 2020–2021 mokslo metais Latvijos mokyklos patvirtino naują požiūrį į mokymąsi ir įdiegė ugdymo turinio reformą pavadinimu „Kompetencijų prieigos įdiegimas mokymo turinyje „Skola 2030“. Šis įvykis lėmė keletą pokyčių mokymo programoje, taip pat tai, kad, pristatant reformą mokyklose, turėjo būti vartojami nauji terminai. Todėl, norėdami sėkmingai įgyvendinti reformą, mokyklų vadovai turi visiškai suprasti naująją mokymo programą ir terminiją. Pristatomo tyrimo tikslas yra ištirti, kokios yra būtinos mokyklų vadovų kompetencijos mokantis dabartinės ugdymo terminijos.

Tikslui pasiekti atlikta teorinės literatūros analizė, mokslinis tyrimas ir statistinė rezultatų analizė; parengta ir atlikta mokyklų vadovų apklausa bei apibendrinti tyrimo rezultatai. Empirinėje tyrimo dalyje išsiaiškinta, kokios yra būtinos su ugdymo terminijos įsisavinimu, vartojimu ir perteikimu susijusios mokyklų vadovų kompetencijos. Tyrimo nustatyta, kad svarbiausios kompetencijos mokantis dabartinės ugdymo terminijos yra socialinė kompetencija, metodologinė kompetencija, savikompetencija ir jų subkompetencijos.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: ugdymas, mokyklų vadovai, ugdymo terminija, ugdymo terminijos kompetencijos.

_________

Received: 10/05/2022. Accepted: 11/11/2022

Copyright © Mārtiņš Driksna

Educational institutions have long been a point of intersection between those who want to get educated and those who teach. Nowadays, when the world is rapidly evolving schools must do the same and evolve with it, to adapt to the needs of students and standards set by the government (Burceva et.al., 2010).

In the school year 2020/2021 schools in Latvia started to adapt the new curriculum presented by the project “Skola 2030”, which means that schools were introduced to the competency-based approach towards students in the instructional content. This reform introduced teachers and heads of schools to new approaches to education and new terminology used to describe the changes, therefore the necessity to identify the competences needed for the acquisition is important.

The success of the adaptation of the new standards is in the hands of heads of schools because their role is essential towards the implementation of the new curriculum. Consequently, to achieve the target they need competences that include both knowledge of education terminology and the ability to use and present new information correctly; if there is a lack of these skills, their level should be improved by attending courses (Jalal & Murray, 2019).

Competences that head of education possesses are a criterion that determines how successful an educational institution will be. When it comes to schools, the responsibility falls on headmasters and it is their competence that is crucial to the process of the implementation of the new curriculum, how the education terminology is used on daily basis to build school’s strategic vision and priorities (Ozols, 2020).

To underline the importance of this research the authors have found out that education terminology is used not only to present new ideas, reforms, or curriculum, but it is also used to evaluate the work of the headmasters and deputy headmasters. Therefore, in order to achieve coherence, terms have to be learned and used accordingly. The issue is ongoing due to the fact that there is no dictionary that gives explanation of a specific term, and mainly heads of schools, teachers and others, who are interested in current terminology of education in Latvia, only can rely on the internet and their digital competences to find the necessary information.

This was confirmed by the 2016 research report which stated that there is a need to develop an explanatory dictionary of educational terms in Latvian and European context (AIC, 2016). In connection with the results of the previously mentioned research, Liepaja University together with the University of Latvia and Riga Stradins University has taken part in the realization of the ESF project’s “Development and implementation of education quality monitoring system” Activity 3.2. “Implemented component research in the research program in education” (Online Glossary of Terminology of Education, Contract No. 23- 12.6/21/3) No. 8.3.6.2/17/I/001.

As a result, since the current “Skola 2030” reform has been initiated without the proper base of terminology, how can heads of schools know and use the terminology of education properly and pass on the knowledge to their staff. Consequently, the acquisition of the necessary information is solely dependent on the competences of heads of school. In addition, this does not only apply to Latvia, but also other countries who borrow terminology from other languages as the competences to acquire it are the same.

Research question: What are the necessary competences of heads of schools in the acquisition of the current terminology of education in Latvia?

The planning of an educational institution’s development is an essential tool for managing education. Planning is the process that can lead to the success or failure of any institution, especially this is important when a reform takes place. The heads of schools have to be informed and able to make the correct decisions, consequently resulting in the situation that headmaster is mainly responsible for the success and the working environment of the school (Dukšinska, 2010).

The term management means that the leader is responsible for staff and their coordination to achieve desired goals, more specifically, to use funds and resources (Bekimbetova & Shaturaev, 2021).

H. Kunzt, who was quoted by N. Delia (2018) explains that management is the art of getting things done using the available people and officially organized groups. Additionally, P. F. Drucker (2006) states that management is a multifunctional organ rather than work itself.

Therefore, management is the main part of the structure of the workplace, which is responsible for successful operation, development, setting goals, managing operations, analysing results, and using appropriate resources, and the main part of school’s management is the headmaster, who is responsible for recruiting the heads of departments.

Heads of schools then must function in a coordinated manner; to achieve successful system management, the heads of departments must work at an efficient rate and must include various positions and correct division of responsibilities (Ozola, 2002). In order to achieve the success, heads of schools have to possess necessary competences for the job, as Razak et.al. (2018) stated there are four main functions that a manager has to do: planning, organization, motivation and control, which nowadays are known as competences. Competence is an ability to do things well, have a great spectrum of knowledge, professional experience, comprehension; being an expert in a specific field (tezaurs.lv, 2021), which is necessary to successfully adapt new terminology.

Lately researchers have made efforts to identify competences of heads of schools. These competences now also include knowledge, skills, abilities and behaviour, therefore, competences are sets of behaviours that are essential to achieve the results (Bartram, 2005).

In the competences dictionary written by K. Vintiša (2011), competences are defined as an instrument of management, which helps employees to understand what is expected of them in the organization. And that there are seven to ten most important competences, the main ones mentioned are interpersonal efficiency competence, thinking and problem-solving competence, personal efficiency competence, task and management competence, leadership competence, awareness of institution values competence.

On the other hand, O. Kareem and M. Kin (2019) state that there are 12 competences, which are necessary for heads of schools, and in comparison to K. Vintiša (2011), there are a lot of similarities, the main ones include such examples as critical thinking, decision making, collaboration, communication, problem solving and other competences. This is emphasized in other studies made by Smith and Riley (2012), Lau (2011), Maguad and Krone (2009), Mason (2007), Paetz et.al. (2011) and many more.

Based on research made previously, the authors have come up with a table that includes the necessary competences of heads of schools (see table 1). The main competences of heads of schools include four groups, which are social competence, methodological competence, professional competence, and self-competence. Authors also emphasize that language proficiency is included in the self-competence part even though it also is part of social competence, for example, communication with colleagues or partners from different institutions, it can also be methodological competence, for instance, creating plans, curriculum, etc. Language proficiency is important part of required competences of the heads of schools because it also involves usage, knowledge, and the ability to pass on the current terminology of education.

|

Competences of heads of school |

|||||||

|

Social |

Methodological |

Professional |

Self- |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

||||||

As stated by T. Wieren (2011) the competences of heads of schools are closely related to the use of the education terminology, which in this particular case is an acquisition of the new terminology provided by “Skola 2030”, as the term must be understood to be used correctly in the working process, therefore, such competences are necessary: critical thinking, language proficiency, motivation, etc.

These competences that are required to attain terminology are also called academic competences, which are defined as the multidimensional knowledge, skills, attributes, including attitude and behaviour, which affect the academic growth (DiPerna & Elliot, 1999, DiPerna, 2005).

Based on the previously mentioned facts the heads of schools have to posses a variety of competences, therefore, leading to the question what the competences of heads of schools in Latvia are that relate to acquisition of the new terminology.

And if the lack of any of these competences is discovered, the necessity for additional education in that field is required. The main methods of management and development of these competences as stated by A. Jalal and A. Murray (2019) are:

• mentoring method;

• seminars and workshops;

• lecture sessions.

The type of the research design is a case study, therefore, the results of the study are not generalizable. The case study is used to find out the competences of heads of schools in Latvia in relation to implementation of the new terminology when adapting school reform “Skola 2030”. The data gathered by this research could help identify the problem behind acquiring the new terminology based on the competences that respondents possess and find important in their work, therefore the recommendations can be made on how to improve the situation. The following research also could be beneficial to other countries, if a lot of terminology is adapted from foreign sources. Quantitative method a survey was used to gather data and reach the objectives of this research and answer the research question. The survey consisted of closed and open-ended questions as well as questions using the Likert scale. The questions were based on the information that was acquired during the theoretical analysis of literature. The survey was created using “QuestionPro” forms.

This study consisted of 61 heads of schools, who work in different parts of Latvia and different levels of education starting with pre-school and ending with highest secondary education. The survey was given using “QuestionPro” forms and distributed using the official e-mails schools had provided on respectable county’s home page in the section of education.

The data were collected with the help of “QuestionPro” forms, where the data was given in a raw format and had to be analysed using a specific program. The program selected for data analysis was statistical program SPSS Statistics 22, where the data were analysed, and based on the information obtained, conclusions were reached and recommendations made.

The results of the survey showed that out of 61 respondents, who were heads of schools, of which 31 or 50.8% were headmasters, and 30 or 49.2% were deputy headmasters or heads of departments, interestingly, nine or 14.75% were male respondents, but 52 or 85.25% were female respondents, which indicates the situation that pedagogy and educational management are mostly studied and chosen as a career by women, it was also emphasised by the press release of National Centre for Education of Republic of Latvia (2021) that in 2019 women accounted for 90% of new students in education.

The average age of respondents was 48.5 years, where the average headmaster was 50.2 years old, but deputy headmaster or head of departments was 46.8 years old. Comparing to the results of TALIS (2018), where the average age of headmasters was 54 years, which in comparison to other OECD countries, where the average age was 52, was higher. The average age seems to have lowered , but it must be noted that 44.26% of respondents were in the group of 51–64 years old.

The education obtained by the respondents showed that most of heads of schools had a master’s degree, which made up 63.93% of all, while 29.51% had a bachelor’s degree, 4.92% had a doctor’s degree, and one respondent also noted another option for professional higher degree. Therefore, it can be concluded that majority or 68.85% of heads of schools have at least a master’s degree, which means that the respondents have extensive experience in working with scientific literature, which consequently could help them to work better with current education terminology.

With the help of the Pearson correlation analysis, it was concluded that education correlates with urbanization (r = - 0.278 and p = 0.03), thus it was concluded that the correlation was negative, but statistically significant, which also indicated that a bachelor’s degree was more common among heads of schools in rural areas and smaller cities, while master’s degree was typical of Riga, large cities, and towns.

The urbanization of respondents’ residence shows that 17 or 27.87% were from Riga, 11 or 18.03% were from the other largest cities of Latvia, 16 or 26.23% were from smaller cities of Latvia and 17 or 27.87% of head of schools were from rural areas.

The type of school which the heads of schools work in were clarified in the next question. The results show that 40.98% of respondents worked in primary schools and also 40.98% worked in secondary schools, while 9.84% worked in state gymnasiums and 8.2% in pre-school establishments. This distribution was logical because based on States Educational Information System (2021), there were a total of 678 general education schools in Latvia, of which 54 or 7.96% were pre-school establishments, 261 or 38.5% were primary schools, 319 or 47.05% were secondary schools. Additionally, there were also 44 or 6.49% of special schools, which did not take part in this survey.

Next question covered the experience of heads of schools in the leading position and overall pedagogical experience. In the leading position as that of the head of school, 47.54% had stated that their experience was below five years, next group which consists of 21.31% had an experience of 11 to 20 years, respondents with experience of 21 or more years took 21.31%, and lastly the smallest group of 9.84% had an experience of six to ten years as heads of schools.

Compared to the overall pedagogical experience only 1.64% or just one respondent was relatively inexperienced compared to others with pedagogical experience of five years or less. Other heads of schools (83.61%) had at least 11 years experience of working in the school.

Question “How often do heads of schools attend professional development courses?” was included in the questionnaire to be able to conclude how the courses affect the development of competences. 52.46% of respondents attend such courses more than three times a year, which indicates the high motivation and desire of these people to develop. In turn, 26.23% of respondents attend courses two to three times a year and 21.31% once a year. The option of not attending courses at all was not mentioned by anyone, again pointing to the high motivation to increase their competences.

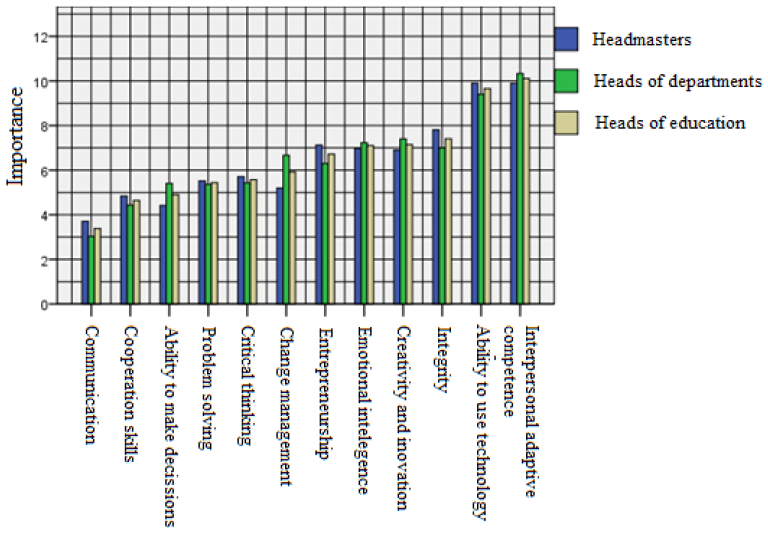

In the following questions, heads of schools had to arrange competences required for the leaders in the order of importance according to them (see figure 1). As the most important competence the respondents marked “Communication”, therefore, it is possible to conclude that it is essential to be able to run the institution successfully, because it helps to understand a colleague, express an opinion, pass on the information, for example, having a successful communication when implementing new terminology to avoid misunderstandings. The second most important competence was “Cooperation skills”, which is closely connected with communication and therefore is equally important. The third most important competence was “Ability to make decisions and take responsibility”, because headmasters are in charge of school and solely responsible for everything that happens there, on the other hand, deputy headmasters or heads of departments although recognized the importance of this competence note that “Conflict and problem solving” was more important, this might be due to the fact that they deal with this situation more often as they are in closer contact with students, teachers and parents, in comparison, headmasters deal with more global problems.

The least important competences found in the survey were “Interpersonal adaptive competence” and “Ability to use technology”. The insignificance of these two competences may come as a surprise, because the former mentioned competence is very closely connected to the most important one communication and cooperation , which ranked number one, therefore, it might be concluded that this term is not very common amongst heads of schools in Latvia, and different terms are used instead. The latter mentioned competence came as a surprise nowadays because everything revolves around today’s technology, perhaps this skill was taken for granted, because everyone knows how to use it and it is used on daily basis and the respondents felt no need to develop this skill any further. According to R. Purvanova and J. Bono (2009) information and communication technology (ICT) can also be used to promote the organization, show how competent and organized the establishment is and that leaders should take this skill into account and use competences such as ICT skills, strategic vision, self-presentation etc.

Heads of schools had to answer the question, which of these competences they possess. Most of respondents noted that they possess all of these competences or specified that they had all of them but some of them needed improvement, without mentioning the skills. Respondents who mentioned specific skills most often named “Communication”, “Critical thinking”, “Decision making”, “Problem-solving”. As stated by A. Jalal and A. Murray (2019) educational leaders should have at least seven to ten competences, but ideally – all of these competences, therefore, based on the answers of the respondents it can be concluded that heads of schools have the necessary competences, but if there is an opportunity to further improve them it must be done, as an example, ICT skills.

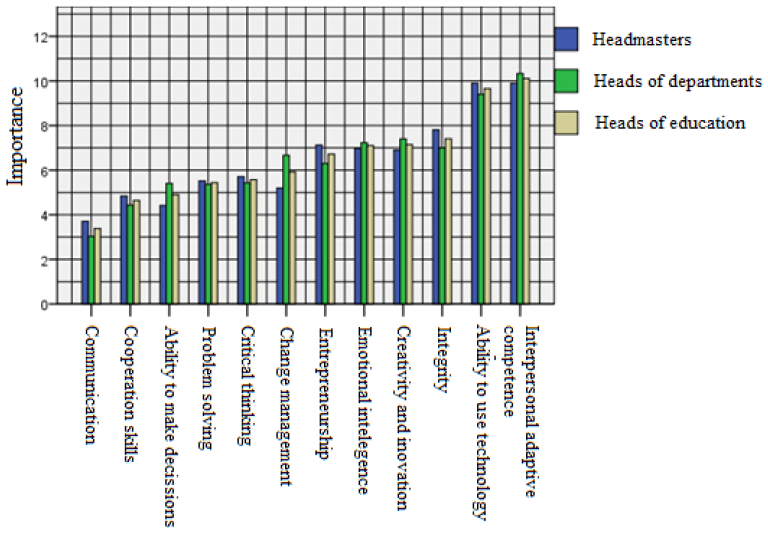

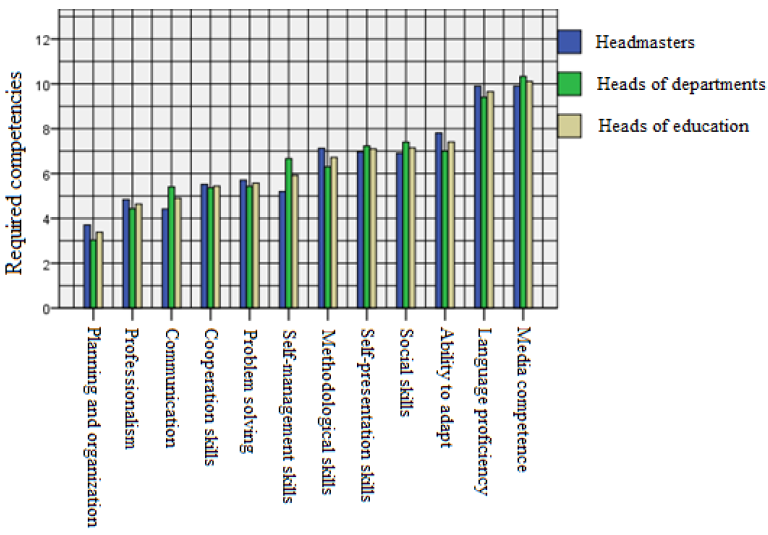

When asked about the skills and competences required in the labour market, respondents (see figure 2) mentioned that the most important one was “Planning and organization”, which was followed by “Professionalism” and “Communication”, the selection of these competences was clear because headmasters must be able to present themselves and successfully communicate with colleagues to solve problems, find compromises, etc. “Media competence”, “Language proficiency” and “Ability to adapt” were named by heads of schools as the least important due to the fact that headmasters and other leading personnel are not involved in advertising and sales, not everyone understands the role of media in the institutions development and advertising. The surprising finding was that the language proficiency was not rated higher, because in comparison to the study made by A. Abdelrazeq (2016) “Media competence” was indeed one of the lowest rated skills, while language proficiency was one of the highest rated skills required for heads of schools. It leads to the conclusion that heads of schools abroad are more involved in projects connected with foreign colleagues as opposite to Latvian leaders mainly delegating people for these duties. That is the reason why authors consider that “Language proficiency” is an important competence to develop by heads of schools in Latvia, due to a lot of terms coming from foreign languages.

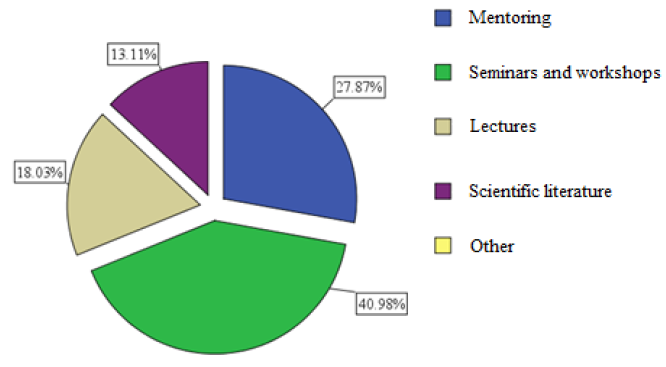

In order to improve competences, 40.98% of heads of schools in Latvia considered seminars and workshops as the best ways, while 27.87% thought that mentoring was the best choice, on the other hand, 18.03% said that the best way was listening to lectures and 13.11% considered reading scientific literature as the best way to improve their competences. While analysing this question several correlations were found, for example, heads of schools with higher education degree, such as doctor’s and master’s degree, prefer to work more individually using scientific literature and lectures, respondents with Batchelors’s degree and part of them with Master’s degree prefer more individual approach, such as mentoring or workshops included in seminars. Very similar correlation was seen when comparing age groups: younger respondents bellow the age of 40 wanted to use seminars, workshops and help from a mentor, but older respondents aged 41 and more wanted to use more individual approach such as lectures or scientific literature.

When asking a question about competence of heads of schools in the current terminology of education, they were asked to name some of the latest terms that were added to their work, but the explanation was not given. The examples of terms were: competency-based approach, metacognitive skills, proficiency, child-centered learning skills, cross-cutting skills, meaningful, differentiation, individualization, taxonomy, proactivity and many more, some of them, when translated to English, lose their meaning.

Heads of schools also used the field to leave comments about the question and implementation of new terminology together with project “Skola 2030” and majority of concerns were that the new reform makes previously known facts more complicated and overflow them with unnecessary new terms, mainly coming from the English language. On the other hand, there were respondents who explained that the new terminology was clear and easy to understand, because they work with it every day and that was part of their job. Therefore, it can be concluded that the acquisition of the new terminology solely rests on the shoulders of heads of schools and their competences to find, learn, adapt and use the information about the new terms. This also points out the situation that content creators of “Skola 2030” project may lack some competences, for instance, counselling, communication and self-presentation.

In the next question about the current terminology of education, the heads of schools had to name terms from project “Skola 2030” that are used on daily basis at work. The list includes terms that were mentioned at least three times, and the number in parenthesis is times mentioned: achievable result (18), self-guided learning (16), feedback (15), individualization (8), summative assessment (7), competence (7), formative assessment (7), personalization (7), values education (6), meaningful (4), self-management (3), media competence (3), digital skills (3), differentiation (3), and cooperation (3).

Based on these results and after examining the Glossary of pedagogical terms (2000), which is the latest official collection of terminology of education in Latvia (the words highlighted in bold can be found in glossary), it can be seen that less than a half of terms were defined, thus concluding that if the heads of schools do not follow the latest educational news or attend courses, then there is no other informative material to use to get to know the terms. The leaders only have to rely on their competences to acquire that information independently, due to the reason that mostly terms are not explained in the Latvian language and have to looked up using foreign scientific literature, which requires such competences as language proficiency, ICT skills, communication skills, organization skills, for example, to organize meetings and discuss the new terms with colleagues, etc.

The Likert scale was used in the following questions. To verify the reliability of the data, an internal consistency check was performed by calculating the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in the SPSS program.

According to K. S. Taber (2017), if the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is greater than 0.7, then the internal consistency of the data is good. In the question about competences and terminology, the results showed that the former’s coefficient was 0.796 and the latter’s coefficient was 0.716, therefore, it can be concluded that the date correlate and this scale can be used.

When it comes to competences, respondents fully agreed, or rather agreed, that the success of educational institution is a collective merit rather than an individual achievement; the process of developing, retaining and educating qualified educators to take up leadership positions is a time-consuming and labour-intensive task; the heads of schools regularly develop their competence by attending courses, seminars, lectures, etc. Heads of schools rather agreed that they are competent to lead and influence subordinates who play a role in developing knowledge about teaching and learning. On the other hand, they partially agreed or rather agreed that the heads of schools have the ability to use informal communication channels and make decisions in order to achieve higher results.

On the other hand, when it comes to terminology, respondents partially or rather agreed that they know and understand the terminology of “Skola 2030”; are able to explain these terms to colleagues; know where to look for information about the latest education terminology; the current education terminology in Latvia has many internationalisms that are poorly translated or explained. They partially agreed that “Skola 2030” terms are well explained and defined, and that the current terminology of education in Latvia is outdated.

The authors conclude that heads of schools agree that success can be achieved by successfully using communication and collaboration skills, leading by example, gaining experience by attending, continuing educational courses, passing this information on to staff, not only through formal, but also through informal channels. However, based on the results of the terminology survey, the current transition to a competency-based approach to education in the context of the “Skola 2030” project is less successful, as the new terminology used by the vast majority of educators is incomprehensible or the meaning is not explained, thus a situation arises that even if the heads of schools have all the necessary competences in the organization and provision of the educational process, it cannot be successfully completed due to partial awareness of the latest developments in education terminology. Therefore, a very important topic is the acquisition of the new terminology.

The next five questions that respondents had to answer were designed as open questions where heads of schools could express their opinion in connection with terminology of education.

Responding to the question on how heads of schools get acquainted with the latest education terminology, the respondents explained that the most frequently used method was attending seminars and courses, which was also mentioned as the best method in previous surveys on improving competences and learning education terminology. Using the materials of the “Skola 2030” project is also a very popular choice, however, it is very difficult to find exact definitions, searching for information on the internet. It was mentioned that scientific literature is used as a resource quite often, to search for information independently, without mentioning a specific form, study glossaries of terms, read normative acts, school regulations, as well as find answers to questions through communication. Thus, the authors conclude that to learn and master the latest education terminology, educational supervisors have to use several skills, such as communication, ability to use technology, language skills, cooperation skills, etc.

Heads of schools were also asked to explain the difficulties they face in their daily use of education terminology, citing the lack of time and the lack of definitions in a single resource, misunderstanding of the meaning of the terms, inappropriate or missing translation or explanation in the Latvian language. Thus, in order to successfully implement the new terminology in schools, a lot of individual work is necessary, because it is often not understood why the new term is needed if a similar word already existed or it is too complicated, or similar to another term, which is confusing. It is important to mention that eleven respondents (18%) left this question unanswered, possibly implying that they do not face any problems in working with the new education terminology.

Furthermore, the heads of schools had to indicate where the meaning of the educational term is sought after, if the term is not understood. A lot of respondents mentioned that the internet was used as the best resource for explaining vague terms, this was confirmed by 27 respondents (44.3%). It was also mentioned that conversations, discussions with a colleague are a good way to find an answer, as well as independent search for information, materials of the “Skola 2030” project, materials published by State Education Quality Service (IKVD), dictionaries, scientific articles, and materials in foreign languages. It should be mentioned that two respondents (3.2%) said that they do nothing to learn the new education terminology. Therefore, it was concluded that heads of schools more rely on their own abilities when searching for the information, thus relying on ICT skills, critical thinking, as well as communication and cooperation, when comparing found information with colleagues.

The next question was used to point out what help is necessary for heads of schools to better understand education terminology. Based on the answers a common idea was identified in order to organize this sphere: it is necessary to create one common resource, where you can find all the necessary explanations together, instead of searching them in several resources and in several ways, in particular, creating an online dictionary of terms, supplementing and updating information in already published dictionaries.

In the last question of the survey, respondents were asked to share information on how the new education terminology is passed on to their colleagues, thus revealing their cooperation and communication skills. The most popular way is pedagogical conferences, because in this way information is passed on to a larger number of people, and this choice was ranked first, while everyday communication was ranked second. Courses organized by the school, individual explanation of terms and use of e-mail were also mentioned as solutions to this problem and four respondents indicated that there was no such formal and / or informal exchange of information in their respectable schools.

Following the results attained in the empirical part of the research, the authors have developed several recommendations for heads of schools to develop their competences in the current education terminology.

It is important to attend appropriate professional development courses to improve competences, with emphasis on the language proficiency, to improve the understanding of new terms.

In order to develop social competence, it is recommended to attend workshops or seminars, thus developing the following components: communication, self-presentation, team leadership, etc.

Improvements to methodological competence can be achieved attending lectures or seminars, therefore, improving planning and organization, strategic vision, etc.

Development of the professional competence can be better achieved talking to more experienced colleagues, therefore, it is recommended to use mentoring program, which will improve awareness of organization’s values, ability to make decisions and take responsibility, etc.

Heads of schools must organize an exchange of experience with heads of different schools across the same or other countries, study the latest scientific research papers and look for the latest terminology, and cooperate with the government on the introduction of new curriculum.

This is a case study at the national level, however, the obtained data on the competence of heads of schools in the current terminology can also be generalized in the practice of schools in other countries, in the improvement of the competence of heads of schools.

This research is important because of the introduction of the new curriculum in schools, due to the realization of project “Skola 2030”; this project introduces new terminology in schools, therefore, it is important to know what are the competences of heads of schools that are required to acquire the current education terminology.

To achieve the results, a survey was conducted and 61 heads of schools from different parts of Latvia participated to get knowledge about competences of heads of schools in the current education terminology.

It was concluded that the most important competences of heads of schools, based on the answers in the survey, were communication, cooperation skills, decision making, problem solving, planning and organization, which the respondents found the most necessary in their overall job and acquiring new terminology. Furthermore, the most important competences required in the labour market were planning and organization, professionalism, communication, cooperation, and problem solving.

In the case of not having a definition for the term, heads of schools must rely on their academic competences to acquire that information independently, firstly, using language proficiency (knowledge of other languages), due to the reason if the term is not explained in Latvian, the definition must be sought in foreign scientific literature, secondly, being able to communicate and organize meetings and discuss terms with colleagues. Therefore, it was brought forward that the best way to improve competences in the current education terminology is to attend seminars, workshops, and mentoring programs.

The research also showed that the current education terminology in Latvia has many internationalisms that are poorly translated or defined, which makes it very difficult to understand and the heads of schools must rely on their competences.

The analysis highlighted that in the acquisition of the current education terminology the most important competences are social competence, methodological competence, self-competence and their subcompetences.

Thus the question of the research “What are the necessary competences of heads of schools in the acquisition of the current terminology of education in Latvia?” has been answered. However, the authors point out that the further study of correlation of specific competences with the usage of terminology is required.

References

Abdelrazeq, A., Koettgen, L., Tummel, C., Richert, A., & Jeschke, S. (2016). What does the lecturers’ employment market advertise for? A higher education skills data analysis. ICERI2016 Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.21125/iceri.2016.0933

Bartram, D. (2005). The Great Eight Competencies: A Criterion-Centric Approach to Validation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1185–1203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1185

DiPerna, J. C., Elliott, S. N. (1999). Development and Validation of the Academic Competence Evaluation Scales. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 17(3), 207–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/073428299901700302

DiPerna, J. C., Elliott, S. N. (2000). ACES. Psychological Corporation.

Drucker, P. F. (2006). The Practice of Management. HarperCollins. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080942360

Dukšinska, O. (2010). Skolas menedžmenta attšitība Baltijas reģionā. [Development of School Management in the Baltic Region] Nordplus horizontal. https://www.izglitiba.daugavpils.lv/Media/Default/Dokumenti/DokumentiLejupieladei/Gramata_latv_1-44lpp.pdf

IZM. (2021). Vispārizglītojošo dienas skolu skaits.[Data on the number of schools in Latvia] VIIS. https://www.viis.gov.lv/dati/visparizglitojoso-dienas-skolu-skaits

Jalal, A. (2019). The Significance of Academic Leadership on Enhancing Higher Education performance. Journal of Higher Education Service Science and Management (JoHESSM).

Kin, T. M., Kareem, O. A. (2019). School leaders’ Competencies that make a difference in the Era of Education 4.0: A Conceptual Framework. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v9-i4/5836

Latvijas Universitāte, Burceva, R., Davidova, J., Kalniņa, D., Lanka, E., & Mackēviča, L. (2010). Novitātes pedagoģijā profesionālās izglītības skolotājiem. [Novelties in pedagogy for vocational education teachers] Latvijas Universitāte. [University of Latvia] https://profizgl.lu.lv/mod/book/view.php?id=12113&chapterid=2685

Lau, J. Y. F. (2011). An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity: Think More, Think Better. (1st Ed.). Wiley.

Maguad, B. A., Krone, R. M. (2009). Ethics and moral leadership: Quality linkages1. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 20(2), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783360802623043

Mason, M. (2007). Critical Thinking and Learning. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 39(4), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00343.x

Ministry of Education and Science Republic of Latvia (2021). Izdots ikgadējais OECD ziņojums par izglītību. [OECD annual report on education] Valsts izglītības satura centrs. [National Centre for Education] https://www.visc.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/izdots-ikgadejais-oecd-zinojums-par-izglitibu

OECD. (2019). Country note: Results form TALIS 2018. https://www.oecd.org/education/talis/TALIS2018_CN_LVA_lv.pdf

Ozola, Z. (2002). Privāto Skolu struktūras un vadības attistība. [Development of the structure and management of private schools] Latvijas universitāte. [University of Latvia] https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/71751235.pdf

Ozols, R. (2020a). Izglītības iestādes pašnovērtējuma ziņojums, sākot ar 2020./2021.māc.g. [Educational institution self-assessment report, starting from 2020/2021 academic year.] [Slides]. IKVD. https://ikvd.gov.lv/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Pasnovertejuma_zinojums_06.11.2020.pdf

Ozols, R. (2020b, September 11). Kritēriji “Administratīvā efektivitāte”, “Vadības profesionālā darbība”, “Atbalsts un sadarbība” un to pašvērtēšana [Criteria “Administrative efficiency”, “Management professional activity”, “Support and cooperation” and their self-evaluation] [Slides]. Ikvd.Gov.Lv. https://ikvd.gov.lv/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Joma_Laba-parvaldiba_11_09_2020.pdf

Paetz, N. V., Ceylan, F., Fiehn, J., Schworm, S., Harteis, C. (2011). Kompetenz in der Hochschuldidaktik. Beltz Verlag.

Purvanova, R. K., Bono, J. E. (2009). Transformational leadership in context: Face-to-face and virtual teams. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.03.004

Razak, A., Sarpan, S., & Ramlan, R. (2018). Effect of Leadership Style, Motivation and Work Discipline on Employee Performance in PT. ABC Makassar. International Review of Management and Marketing, 8(6), 67–71. https://doi.org/10.32479/irmm.7167

Šalme, A., Skujiņa, V., Koķe, T., Markus, D., Beļickis, I., Blūma, D. (2000). Pedagoģijas terminu skaidrojošā vārdnīca. [Glossary of pedagogical terms] Zvaigzne ABC.

Shaturaev, J., Bekimbetova, G. (2021). The difference between educational management and educational leadership and the importance of educational responsibility. InterConf.

Smith, L., Riley, D. (2012). School leadership in times of crisis. School Leadership & Management, 32(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2011.614941

Taber, K. S. (2017a). The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

Taber, K. S. (2017b, June 7). The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. SpringerLink. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2?error=cookies_not_supported&error=cookies_not_supported&code=cb5550d9-d247-429c-bb58-3bd4c3e0d70a&code=129d17d2-6a24-4725-b92d-7ecd6363f20a

Tēzaurs [Thesaurus]. (2021). Tēzaurs. [Thesaurus] Retrieved 18 June 2021, from https://tezaurs.lv/

“Valahia” University in Targovishte, Doctoral School of Management, & Delia, N. (2018). The Concept of Leadership. “Ovidius” University Annals, Economic Sciences Series. https://stec.univ-ovidius.ro/html/anale/RO/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/24.pdf

van Wieren, T. (2011). Academic Competency. Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79948-3_1445

Vintiša, K. (2011). Kompetenču vārdnīca. [Dictionary of Competencies] Creative Technologies.