Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2021, vol. 47, pp. 122–142 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2021.47.9

Implementing the Personalised Learning Framework in University Studies: What Is It That Works?

Simona Kontrimiene

Vilnius University

simona.kontrimiene@flf.vu.lt

Vita Venslovaite

Vilnius University

vita.venslovaite@fsf.vu.lt

Stefanija Alisauskiene

Vytautas Magnus University

stefanija.alisauskiene@vdu.lt

Lina Kaminskiene

Vytautas Magnus University

lina.kaminskiene@vdu.lt

Ausra Rutkiene

Vytautas Magnus University

ausra.rutkiene@vdu.lt

Catherine O’Mahony

University College Cork

catherine.omahony@ucc.ie

Laura Lee

University College Cork

l.lee@ucc.ie

Hafdís Guðjónsdóttir

University of Iceland

hafdgud@hi.is

Jónína V. Kristinsdóttir

University of Iceland

joninav@hi.is

Anna K. Wozniczka

University of Iceland

akw1@hi.is

Abstract. Personalised learning embraces the elements of mutual ownership by learners and teachers, flexible content, tools and learning environments, targeted support, and data-driven reflection and decision making. The current study utilises a mix of instrumental case study (Stake, 1995) and deductive thematic analysis (Braun, Clarke & Terry, 2015; Terry et al., 2017) methods to explore the accounts of students of two teacher education study programmes at Vilnius University. The programmes were innovated to include practices of personalised learning in line with the framework developed by partners of the Erasmus+ Strategic Partnership Project INTERPEARL (Innovative Teacher Education through Personalised Learning). The results yielded three major themes which capture the successes and setbacks the students face, namely, personalisation in vivo: facilitation of growth as a would-be teacher; personalisation not manifest: what does not work; and personalisation in the making: the dos and don’ts.

Keywords: Personalised learning, teacher education, case study, Stake, thematic analysis.

Personalizuoto mokymo(si) koncepcijos taikymas universitetinėse studijose: kaip tai veikia?

Santrauka. Personalizuotą mokymą(si) sudaro keturi pagrindiniai principai: 1) abipusė mokytojo ir besimokančiojo atsakomybė; 2) lankstus turinys, priemonės ir mokymosi aplinka; 3) tikslingas mokymas(is); bei 4) duomenimis grindžiami sprendimai ir refleksija. Šiame tyrime taikant instrumentinės atvejo studijos (Stake, 1995) ir dedukcinės teminės analizės (Braun, Clarke & Terry, 2015; Terry ir kt., 2017) metodus buvo tiriamos dviejų Vilniaus universiteto mokytojų rengimo studijų programų studentų savistatos apie mokymo(si) personalizavimo patirtis studijų metu. Programos buvo atnaujintos įtraukiant į jas inovatyvias personalizuoto mokymo(si) praktikas pagal „Erasmus+’ strateginių partnerysčių projekto „Inovatyvus mokytojų ugdymas taikant personalizuotą mokymą(si)’ (angl. Innovative Teacher Education through Personalised Learning (INTERPEARL) partnerių sukurtas gaires. Rezultatai atskleidė tris pagrindines temas, kurios atspindi sėkmingas ir nesėkmingas studentų patirtis: personalizavimas in vivo: būsimojo mokytojo augimo skatinimas; kai personalizavimo nėra: kas neveikia; ir personalizavimo tapsmas: ką daryti, o ko ne.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: personalizuotas mokymas(is), mokytojų rengimas, atvejo studija, Stake, teminė analizė.

___________

Received: 19/05/2021. Accepted: 09/09/2021

Copyright © Simona Kontrimiene, Vita Venslovaite, Stefanija Alisauskiene, Lina Kaminskiene, Ausra Rutkiene, Catherine O’Mahony, Laura Lee, Hafdís Guðjónsdóttir, Jónína V. Kristinsdóttir, Anna K. Wozniczka

Introduction

Recent significant changes in education have raised questions about the basis of the university system and its operation—what to teach, what to study and how to provide shared knowledge to students. In this respect, the question of effective organisation of modern educational programmes assumes new features that facilitate interaction between students and teachers with different teaching and learning codes and technologies.

The Yerevan Ministerial Communiqué (2015), one of the main political documents of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) which lays down a renewed vision of the EHEA and sets goals for the upcoming period of the Bologna Process, has set forth a collective ambition for the 47 member countries to support higher education institutions and staff in promoting pedagogical innovation in student-centred learning environments. To that end, study programmes should enable students to develop the competences that can best satisfy personal aspirations and societal needs through effective learning activities. These should be supported by transparent descriptions of learning outcomes and workload, flexible learning paths, and appropriate teaching and assessment methods.

It follows that one of the essential features of today’s education is the orientation towards the active role of the learner, where the educational process is flexible and based on shared responsibilities and learning goals meaningful for the learner. It could be argued that much of today’s education is at least to a degree personalised, i.e., focused on the strengths, needs and interests of each learner, which creates opportunities for them to choose what, how, where, and when to study (Patrick, Kennedy & Powell, 2013). Students today expect a flexible and personalised study process, blended ways of learning, and a wide variety of assessment methods and tools. Yet, there is a dearth of research on the conceptualisation and practicality of implementation of personalised learning (PL) in the context of university studies as this concept, albeit tossed around a lot in educational circles, is not fixed. To name a few, Alisauskiene et al. (2020a)1 explored the role and initiatives of students in planning and improving the content of the study subject and self-assessment of study results within the personalised learning (PL) framework. Another study by Alisauskiene et al. (2021) introduced the PL framework and two related concepts, Learning Scenarios and Learning Design, as well as their practical implementations in the study process. Berge (2011) explored the case for personalised learning by tying it to mobile learning (mLearning) and viewing PL as both a set of customisable tools and a philosophy that allows the individual to create an effective learning environment as a means of learning what is personal or relevant to an individual learner. Pogorskiy (2015) introduced the role of personalisation in the learning process with a focus on the concept of a ‘world view’, which makes it increasingly possible to identify topics potentially relevant to an individual.

Admittedly, what is universally known about personalised learning is that it implies multiple pathways to learning and resists the notion that all students learn the same way, yet what evidence there is reveals that PL has been understood and implemented in diverse ways; hence, educators’ conceptions of this construct might be informed by the experiences of students. To help fill this gap, the current study aims to build on the conceptualisation of the construct of personalised learning developed by the partners of the INTERPEARL project and explore the case of practical implementation of innovative practices of personalised learning in two teacher education study programmes at Vilnius University.

Personalised learning: what it is and what it is not

Traditionally, a usual hallmark of university learning has been the separation of knowing and doing in which there is a failure to access knowledge relevant to solving the problem at hand. Information is often stored as facts rather than tools and the knowledge gained remains ‘inert’. As famously noted by Herringon and Oliver (2000, p. 23), ‘When learning and context are separated, knowledge itself is seen by learners as the final product of education rather than a tool to be used dynamically’.

Many current traditional educational landscapes give a one-size-fits-all feel, where each student’s education is not differentiated and all are expected to progress at the same time through the same courses (Patrick, Kennedy & Powell, 2013). Personalisation, on the other hand, pushes educators to think outside the box by emphasising the need for learners to be involved in designing their own learning process (Campbell et al., 2007). Hence, in a personalised learning environment, learners have the agency to set their own goals for learning, create a reflective process to attain those goals and be flexible enough to take their learning outside the confines of the traditional classroom.

Our contention is that personalised learning rests, first and foremost, on the philosophical perspective of constructivism. It is the learner’s construction of their social reality rather than objective input that determines what they attend to and how they think, feel, and behave in a complex social world (Bless & Greifeneder, 2018). In addition, learners can influence the amount of processing allocated to a particular task via the automatic and controlled top-down and bottom-up processes (the top-down information processing is guided primarily by prior knowledge and the expectations individuals bring to a situation, whilst the bottom-up information processing is influenced primarily by the stimuli from a given situation) (Bless & Greifeneder, 2018). For all that, a student in the personalised learning process simultaneously externalises their own being into the learning experience and internalises the latter as their newly constructed reality.

The father of constructivism Jean Piaget (1969, 1972, 1974) believed that people are always trying to reach the state of equilibrium, whereby the learner discards his misconceptions, adopts scientific explanations that best fit the situation, and constantly tests the adequacy of his ideas through assimilation and accommodation. Actual learning happens through accommodation, in which scientific knowledge is not simply transferred from teacher to student but rather students implement their own conceptual changes enabled by teachers who are student-centred and act as facilitators of learning, not as authorities who transmit information to students. It is important for the teacher to examine each student’s cognitions and develop instructional techniques which create a cognitive conflict to be resolved. Indeed, students must actively participate in learning, which greatly depends on the shared experiences of students, peers, and the teacher; hence, cooperative learning is a major teaching method used in the constructivist classroom2.

Importantly, personalised learning is closely related to individualised and differentiated learning (Bray & McClaskey, 2012; Alisauskiene et al., 2020b), although the first is student-centred, whereas the other two are teacher centred. Individualisation refers to the learning needs of different learners. Learning goals herein are the same for all students but they can progress through the material at different speeds according to their learning needs. Differentiation refers to instruction that is tailored to the learning preferences of different learners. Again, learning goals here are the same for all students but the method or approach of instruction varies according to the preferences of each student or what research has found works best for students like them. In contrast, personalisation refers to instruction paced to learning needs tailored to learning preferences and specific interests of different learners. In an environment that is fully personalised, the learning content as well as the method and pace may all vary (hence, personalisation encompasses individualisation and differentiation) (Bray & McClaskey, 2012).

The INTERPEARL project aims at developing and testing a new PL framework within teacher education to enhance and transfer innovative PL practices across teacher education programmes. The objective is to provide a personalised learning journey for aspiring teachers which would enable them to understand and experience its potentially transformative impact so that they, in turn, would enable their own future students to become confident, reflective and autonomous learners. The INTERPEARL model of personalised learning (Alisauskiene et al., 2020b) recognises the joint responsibility of the learner and teacher for the learning endeavour. Therefore, the theory of personalisation places the co-creation of learning at the front, encouraging educators to think outside the box and acknowledge the need for learners to be involved in designing and reflecting on their own learning process (Zmuda, Curtis & Ullman, 2015, as cited in Alisauskiene et al., 2020b).

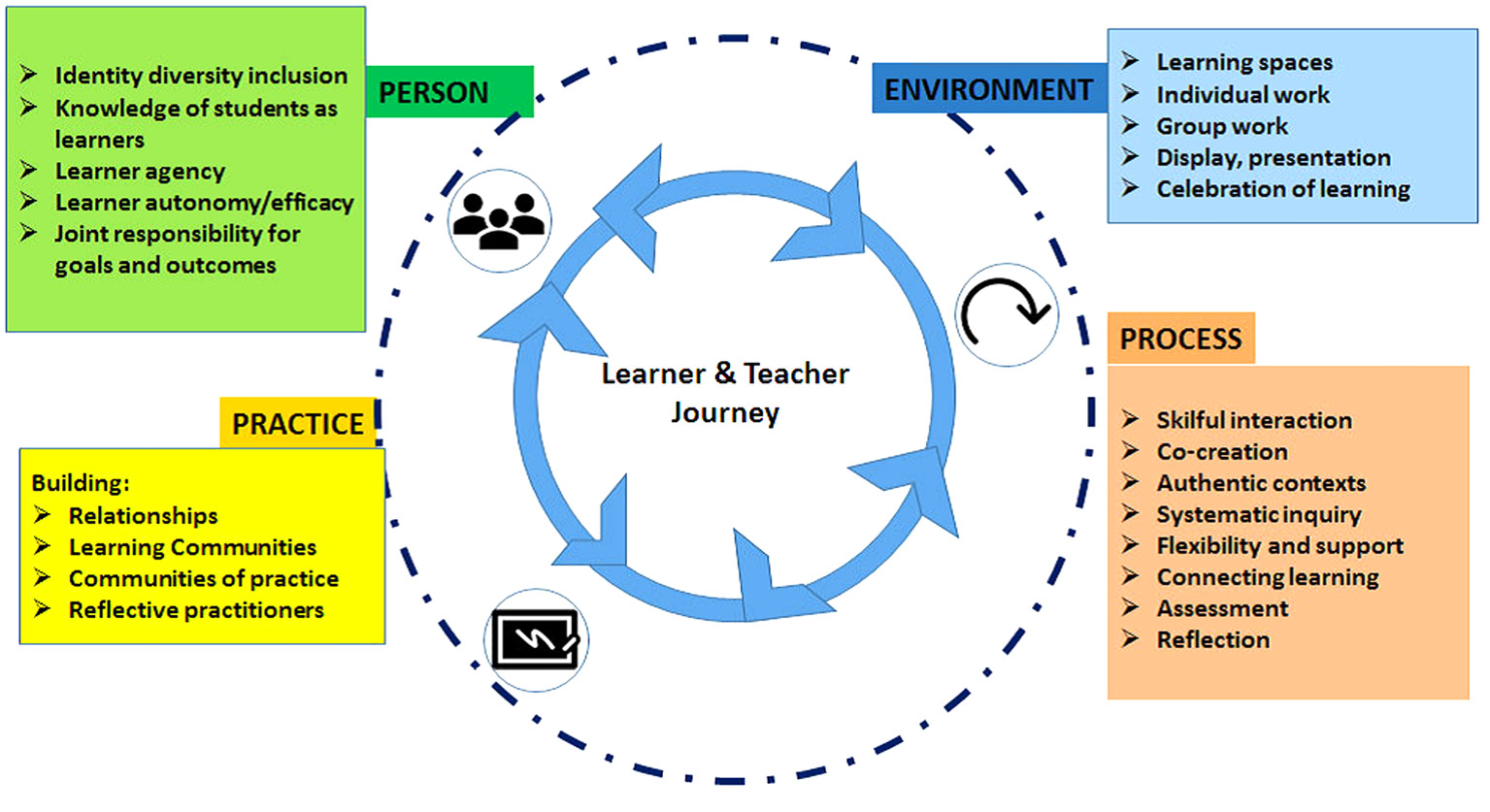

The INTERPEARL model envisages personalised learning as an interactive learner and teacher journey involving four core dimensions: Person, Environment, Process, and Practice (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Model of Personalised Teacher Education (INTERPEARL team, 2020).

All in all, personalisation entails starting the process of learning with the learner, connecting with their interests, passions, and aspirations, selecting appropriate technology and resources to support their learning, building a network of peers, experts, and teachers to guide the learning, and, lastly, implementing summative assessment not only of and for but also as learning. Personalised learning represents a shift away from the model in which students consume information through independent channels such as the library, a textbook, or a learning management system, moving instead to a model where students draw connections from a growing matrix of resources and take up responsibility for own progress. In addition, PL enables the learner to continue learning after formal courses have ended and makes lifelong learning possible.

To look at the practicality of application of PL in educational settings, the current study utilises the instrumental case study method (Stake, 1995) to explore the practice of implementation of innovative practices of personalised learning within teacher education programmes at Vilnius University through the accounts of students.

Method

The Institute of Educational Sciences at Vilnius University Faculty of Philosophy has implemented changes using the PL model in the modules General Pedagogy and Final Thesis of two teacher education study programmes, School Pedagogy (a postgraduate professional pedagogical study programme) and Subject Pedagogy (a minor study programme). All the four modules aim to use personalisation of the learning process in a set of learning activities designed to help students attain the expected learning outcomes. To that end, the selected modules employ interactive scenarios to support problem-based or case-based active learning. In the process, teachers first identify the students’ profiles based on their needs, strengths, challenges, aptitudes, interests, and aspirations, then take into consideration the students’ preferences for engagement strategies and build on this knowledge. Next, the teachers develop adaptable learning scenarios and flexible blueprints for creating instructional goals and selecting methods and materials. Lastly, the teachers employ assessment as learning by actively engaging students to reflect and critically assess their learning progress.

The specificity of personalisation of learning in the four modules is as follows:

• The modules General Pedagogy, which aim to equip students with theoretical foundations of the science of pedagogy, develop their pedagogical competence and acquaint them with teacher work during professional training placements at school, have been innovated to incorporate the scenario-based PL model in their three parts, respectively. First, in the parts of the modules entitled Philosophy of Education, each student selects a topic for their academic essay based on their profile, interests and subject(s) taught. Some students choose to write an essay that later serves as a philosophical foundation or a literature review for their final thesis. Students also select topics for seminars based on what is currently most pertinent to their interests. Second, in the parts of the modules entitled History of Pedagogy, students choose the type of oral or written assessment––a written assignment or participation in a debate on the topic that is of interest to them. Third, in the parts of the modules entitled Designing a Pedagogical System, students choose to write a subject lesson plan or an integrated lesson plan as an individual assignment, or draft and present a group project about a future school vision/scenario.

• The modules Final Thesis, which aim to help students improve their practical abilities to work at school and develop the social science research competence via conducting an empirical research study, have been innovated so that students may choose the topic of the final thesis relevant to their interests and expertise and attend seminars on the quantitative and/or qualitative research methods they plan to use in their research, during which they refine their vision of the final thesis and draw up research designs.

To evaluate the implementation of PL practices in the two teacher education study programmes, the current study explores the experiences of their recipients, students of the two programmes. To that aim, the study utilizes a mix of instrumental case study (Stake, 1995) and deductive thematic analysis (Braun, Clarke & Terry, 2015; Terry et al., 2017) methods.

Stake’s (1995) case study method rests on interpretive orientations towards a case which include ‘naturalistic, holistic, ethnographic, phenomenological, and biographic research methods’ (Stake, 1995, p. xi). Stake (1995) notes that a case is a specific, complex, functioning thing, an integrated system which has a boundary and working parts3. To meet the aim of our study, we utilised the case of one institution (Vilnius University) to illustrate how practices of personalisation are implemented in it.

Participants. Purposive sampling was used to recruit students from the two Vilnius University teacher education SPs, the postgraduate professional pedagogical SP School Pedagogy and the minor SP Subject Pedagogy. The total sample included 46 participants, 23 students (18 females and 5 males) from the minor SP Subject Pedagogy ranging in age from 21 to 24 years (M = 22.3, SD = .9 years) and 23 students (19 females and 4 males) from the postgraduate professional pedagogical SP School Pedagogy, their age ranged from 23 to 47 years (M = 35, SD = 8.2 years).

Data collection. The data were collected via an online survey. Students were sent the link to the survey via e-mail and completed the survey on a virtual platform. The survey included demographic and open-ended questions which tapped into the recognisability of implementation of the key components of PL in the two modules, General Pedagogy and Final Thesis, and suggestions for the future, e.g.: ‘In personalised learning, the ability of students to reflect on learning and provide feedback to the teacher is important. Did you recognise this in the modules General Pedagogy and Final Thesis? How should such practices be encouraged?’; ‘Did you have the opportunity to collaborate with teachers by setting learning goals and choosing methods for self-assessment? How useful was it?’; ‘How can activities be organised to help students contribute to the planning of learning content to meet their own interests? How was this done in the modules General Pedagogy and Final Thesis?’; ‘Please share your particularly successful and unsuccessful learning experiences from the lectures or seminars of the modules General Pedagogy and Final Thesis’, etc.

Data analysis. To reach a thorough understanding of the case, we employed the strategies of direct interpretation and categorical aggregation to combine emergent properties and make tallies in intuitive aggregation4. For these purposes, the data were analysed thematically (Braun, Clarke & Terry, 2015; Terry et al., 2017): first, the students’ accounts were read and reread multiple times, then coded for instances where students described their PL-related learning experiences. Our analysis mostly employed latent coding, whereby the codes captured implicit meanings behind our participants’ words, such as ideas, concepts and assumptions which may have been not stated explicitly but allowed us to discover personalisation in learning. Data coded to broad conceptual categories were analysed deductively5 to derive explications of patterns within and across students’ accounts (Braun, Clarke & Terry, 2015; Terry et al., 2017). The analysis was first performed independently and then in team discussions to compare interpretations, further develop themes, and select illustrative quotes. In the process we drew on our model of PL to advance the emergent themes, extend the angle of vision upon which much of the PL has been based, and shape insights and applications of PL in practice.

Results

The results of our thematic analysis suggest that instances of PL in the modules General Pedagogy and Final Thesis of the two teacher education study programmes at VU are captured by three major themes: personalisation in vivo: facilitation of growth as a would-be teacher; personalisation not manifest: what does not work; and personalisation in the making: the dos and don’ts (see Table 1). Within each of these themes, students envisioned aspects of PL that were indicative of their own successes and setbacks during studies.

Personalisation in vivo: facilitation of growth as a would-be teacher. This major theme was endorsed by the biggest number of students and contains the subthemes being given voice and choice; stretching own limits; having your needs met; reflection and feedback; plunging into depth; giving diversity and breadth; flexibility in assessment; benefits for the future. Students are not unanimous in how they see personalisation in their teacher education programme as they highlight different aspects which facilitate PL. Yet most importantly, the strategies and teaching methods proposed by teachers within the two programmes are seen by most students as conducive of personalisation and growth. They stress the importance of being given voice and choice, saying that ‘Teachers and administration always encouraged us to express wishes and suggestions regarding the content of learning’ (Participant 34, professional pedagogical SP). In the words of Participant 42 (professional pedagogical SP), ‘Of course, this freedom of choice was useful as such a choice raises a lot of questions directed to the self: what do I want? what do I really care about? and although the moment of choice is difficult, it leads to many interesting and beautiful creations that are more meaningful. Harder but more interesting, and, of course, more useful’.

Another important subtheme that emerged from the students’ accounts was stretching own limits. Although it was endorsed by only three students from the professional pedagogical study programme, it indicates that activities covered in the four modules allowed those students to try out something bigger than what one is used to. ‘I chose tasks that interested me. Some tasks I chose because I hadn’t tried one way or another, and this gave me the opportunity to try things out, to stretch my own limits’ (Participant 24, professional pedagogical SP). In the words of Participant 31 (professional pedagogical SP), ‘The student can choose by what is more interesting to him, what is easier, or maybe the other way round, by what can pose a challenge to him. Besides, you find it easier to plan your time when you are in a position to choose the assignment yourself.’

Practices of personalisation also give the students the feeling that they have their needs met. Participant 37 (professional pedagogical SP): ‘Some lectures would start with discussions of our expectations, of what has been planned for us and what options we had to introduce adjustments based on our needs. […] In our case, the freedom of choice was very much in line with our needs.’ Participant 35 (professional pedagogical SP): ‘Of course, we had both our scientific and pragmatic or life interests met. Since I also work in the field of museums, I have a chance to explore my field of work from a scientific perspective.’

Personalisation implies reflection and feedback as a conscious effort to think about personal experiences, to develop insights and conceptualise and reframe them. Nine participants saw its unquestionable benefit, e.g., Participant 22 (minor SP) notes: ‘I did that. To show that the comments are taken into consideration and that change is taking place, not to ignore everything.’ Participant 38 (professional pedagogical SP): ‘This is very important and useful because students pin down and sort out for themselves what was difficult, what they have learned, what questions arose and why.’

Two more aspects of personalised learning experiences are that they greatly enrich the process of learning as for one thing, they facilitate students’ plunging into depth and secondly, they give (the studies) diversity and breadth. The latter aspect was especially prominent as it figured in the vivid accounts of ten students. E.g., Participant 1 (minor SP) states: ‘All such tasks help you to plunge into the chosen topic.’ Participant 32 (professional pedagogical SP): ‘[…] it was interesting, it broadened my horizons.’ Participant 13 (minor SP): ‘Activities were useful because they differed a lot. We had a chance to try out different study methods and see what works worse and what works better. It is also useful because during a big number of activities we focused only on our subject, which is good because it does not distract, does not mix with other things that are not relevant to us. But there were also activities where we could see to some extent the work of students from other study fields, our yearmates, and learned something useful from the methods they use.’

Flexibility in assessment, another subtheme that emerged from our findings, was mentioned by four students, e.g., Participant 9 (minor SP) said: ‘Our activities were useful as they brought us into both the teacher’s profession and the teaching/learning process in a more relaxed form, not in the form of final exams for which you have to “cram” certain things and then leave them as factual knowledge.’ Participant 34 (professional pedagogical SP): ‘I felt personalisation in part because I was able to choose at my discretion the topics to explore and forms of assessment.’

Last but not least, our findings suggest that personalised learning provides important benefits for the future as envisioned by nine students. In the words of Participant 19 (minor SP), ‘All activities allowed a deeper understanding of the educational science, cognising, searching for information and applying it in the future.’ Participant 34 (professional pedagogical SP): ‘It was useful because it allowed me to bring the tasks to where I am and adapt them to the analysis of my professional realm. It also allowed me to look at my profession from a certain novel perspective, to draw on the feedback and evaluation of our teachers.’ And the ideas expressed by Participant 24 (professional pedagogical SP) are especially hopeful: ‘There have been no setbacks, at least for me. […] It is really nice to collaborate and study. I feel like a lot has changed at university compared to the times I studied earlier. Changed for the better. Thank you and wish you the best luck.’

Table 1. Themes, subthemes, and a selection of illustrative verbatim quotations reflecting experiences of students with PL practices.

|

PL Themes |

Subthemes |

Verbatim |

|

Personalisation in vivo: facilitation of growth as a would-be teacher |

Being given voice and choic |

The teacher must pay attention to what is most relevant and useful to students. I think this came to the fore during our studies because several teachers in the first lectures or seminars asked the students what they wanted to know/learn and tried to teach what the students asked for. (P3, minor SP) Our subject pedagogy teachers generally had a greater focus on detail and common human values and many things were tailored to us, students. Teachers usually explained plans very thoroughly, which made us feel safe and eased the preparation. […] Teachers often encouraged us to write a letter or message through MS Teams and refine the study topics, and in some cases, they even adjusted the tasks to student needs. (P11, minor SP) Choice gives you the freedom for self-expression. E.g., the debate task was especially enjoyable because it covered several integral aspects of learning: from looking for the right information and brainly presenting your arguments to time planning and developing oratory skills. (P28, professional pedagogical SP) Teachers and administration always encouraged us to express wishes and suggestions regarding the content of learning. (P34, professional pedagogical SP) [My research interests] were definitely considered as I wrote my final thesis on the topic that was closely related to my ‘field’ of studies. (P11, minor SP) It is very useful and necessary because choice gives you more autonomy, which allows you to feel partly responsible for things yourself, allows you to decide for yourself what makes it more interesting, meaningful, and clearer when you have to account for that subject. (P20, minor SP) […] the freedom of choice gives me the opportunity not to do what I don’t want to do and to do what is much more interesting, taps into my completely different competences and is a collaboration rather than a control that I have to do just that and not something else. (P18, minor SP) I find our activities useful because you choose not only on the basis of your personal ability but in general, what interests you. This makes the work easier. (P11, minor SP) [Being given choice] was useful as I could choose things that were closer to me. […] You could channel your interests in directions that are principal to you. (P25, professional pedagogical SP) We were definitely given the liberty to discuss, to express our opinions and reasonable wishes. (P35, professional pedagogical SP) Of course, this freedom of choice was useful as such a choice raises a lot of questions directed to the self: what do I want? what do I really care about? and although the moment of choice is difficult, it leads to many interesting and beautiful creations that are more meaningful. Harder but more interesting, and, of course, more useful. (P42, professional pedagogical SP) |

|

Personalisation in vivo: facilitation of growth as a would-be teacher |

Stretching own limits |

The student can choose by what is more interesting to him, what is easier, or maybe the other way round, by what can pose a challenge to him. Besides, you find it easier to plan your time when you are in a position to choose the assignment yourself. (P31, professional pedagogical SP) The seminars were very personalised, we dealt with specific complex issues that arose. (P25, professional pedagogical SP) |

|

Having your needs met |

Some lectures would start with discussions of our expectations, of what has been planned for us and what options we had to introduce adjustments based on our needs. […] In our case, the freedom of choice was very much in line with our needs. (P37, professional pedagogical SP) [My needs] were taken into account and I was supported in my choice of the topic I was interested in and cared for, which was application of the multimodal method of education. (P29, professional pedagogical SP) Teachers took into account the many aspects of distance teaching and learning and the situation of students in general, highlighted the main things we needed to focus on, and there were teachers who were very concerned about the students‘ well-being, which means a lot as psychological support is a driver for motivation, especially in such a stressful period. (P43, professional pedagogical SP) Of course, we had both our scientific and pragmatic or life interests met. Since I also work in the field of museums, I have a chance to explore my field of work from a scientific perspective. (P35, professional pedagogical SP) We would often see that the teacher was responsive and tried to respond to our emerging needs. (P35, professional pedagogical SP) Teachers provide opportunities to choose topics for projects, look into students‘ wishes and preferences before the start of the course, and adjust the course programme accordingly. (P45, professional pedagogical SP) Of course, this [the possibility to choose] is very useful because you are not stuck in narrow frames. The group is big, and the people in it are different. Some are better at and feel more comfortable with oral assignments, others with written. The freedom to choose from several options allows you to select the desired task based on your interests and abilities. (P30, professional pedagogical SP) [When I was writing the final thesis], the approach I witnessed was very flexible to the topic I chose, which was perhaps a little remote to the general subject of the SP but very relevant to primary education in which I was working at the time. (P28, professional pedagogical SP) They [the practices of personalisation] were successful in every way––all the attentiveness, consideration, hearing us out. (P41, professional pedagogical SP) I would like to express my gratitude to those teachers who agreed to modify and adapt their programme to student requests that arose during the lectures. I would think that teachers would not really want any of their students to poke with their advice into what topic they should give and what not. (P39, professional pedagogical SP) |

|

|

Personalisation in vivo: facilitation of growth as a would-be teacher |

Reflection and feedbac |

During the studies we wrote a lot of reflections and teachers gave us personal feedback; there was a lot of it. I could say that this is encouraged enough. (P11, minor SP) We used reflection almost all the time in our studies. I think it is a very good thing that helps you realise what progress has been made over this or that period of time, and it is also a good way to self-assess your efforts. (P23, minor SP) This often allowed the lecture to be tilted in the desired direction when there were enough students who elaborated on the same issue or shared their own practical situations. (P44, professional pedagogical SP) We were able to communicate openly. Have our say and share. And our teachers listened to us and advised us. (P36, professional pedagogical SP) I did that. To show that the comments are taken into consideration and that change is taking place, not to ignore everything. (P22, minor SP) This was always done, especially as teachers encouraged students to provide feedback. (P19, minor SP) I enjoyed reviewing everything by brooding about everything and then getting feedback from the teacher. (P4, minor SP) This is very important and useful because students pin down and sort out for themselves what was difficult, what they have learned, what questions arose and why. (P38, professional pedagogical SP) |

|

Plunging into depth |

All such tasks help you to plunge into the chosen topic. (P1, minor SP) Useful because they encouraged deep engagement in tasks. (P23, minor SP) […] we discussed together the methods of assessment and topics of the courses we wanted to explore in depth. (P5, minor SP) |

|

|

Giving diversity and breadth |

Yes, I think such activities were useful because by doing them, we not only had the opportunity to learn something new (for example, to explore one or another philosophical perspective), but also to develop lesson plan writing skills, discuss the strengths and weaknesses of sample plans, etc. (P12, minor SP) All the teachers often asked us what else we would like to know and shared in the VLE their knowledge, literature and additional slides in the fields that interested us. (P35, professional pedagogical SP) Some teachers recommended to us books or research studies, but this was not clearly defined, rather it was offered as additional literature that you could read in your spare time, not as part of the teaching/learning process. (P1, minor SP) Often, when doing some written assignments (e.g., alternative activity, philosophical essay, analysis of the educational environment, description of the organisation of distant teaching/learning at school, characteristics of the class you teach), teachers encouraged us to look for additional literature and aspects of the themes we explored. The good thing is that often there was already some literature list or a few readings that we could use as a scaffolding. (P12, minor SP) […] it was interesting, it broadened my horizons. (P32, professional pedagogical SP) It [personalisation] was encouraged during self-study tasks, when each of us had to prepare lesson plans, presentations, etc. Or when reading texts and thinking about answers to questions on those texts. (P13, minor SP) Activities were useful because they differed a lot. We had a chance to try out different study methods and see what works worse and what works better. It was also useful because during a big number of activities we focused only on our subject, which is good because it does not distract, does not mix with other things that are not relevant to us. But there were also activities where we could see to some extent the work of students from other study fields, our yearmates, and learned something useful from the methods they use. (P7, minor SP) |

|

|

|

Flexibility in assessment |

I felt personalisation in part because I was able to choose at my discretion the topics to explore and forms of assessment. (P34, professional pedagogical SP) More flexible forms of assessment allow you to look deeper into the matter, to look at it from diverse perspectives. (P9, minor SP) […] it was possible to choose ways of assessment that suited us. (P27, professional pedagogical SP) Our activities were useful as they brought us into both the teacher‘s profession and the teaching/learning process in a more relaxed form, not in the form of final exams for which you have to ‘cram’ certain things and then leave them as factual knowledge. (P9, minor SP) |

|

Benefits for the future |

All activities allowed a deeper understanding of the educational science, cognising, searching for information and applying it in the future. (P19, minor SP) It was useful because it allowed me to bring the tasks to where I am and adapt them to the analysis of my professional realm. It also allowed me to look at my profession from a certain novel perspective, to draw on the feedback and evaluation of our teachers. (P34, professional pedagogical SP) I think this [personalisation] gives us opportunities to develop different competences. (P33, professional pedagogical SP) It was helpful because I had the opportunity to explore topics that are important to the teacher’s overall literacy. Thinking through the integrated lesson plan was also helpful as I plan to use it in my future career. (P45, professional pedagogical SP) There have been no setbacks, at least for me. […] It is really nice to collaborate and study. I feel like a lot has changed at university compared to the times I studied earlier. Changed for the better. Thank you and wish you the best luck. (P24, professional pedagogical SP) These courses are fun and rewarding. Maybe it is difficult to submerge into the philosophy and history of pedagogy from the beginning of the programme. Maybe not everyone understands the essence of such courses. To me, they became more relevant in the second semester, and were merely interesting in the first. Yet now I would definitely take those courses differently if I had the opportunity to cover them anew. The Final Thesis course is good in the sense that it does not burden students but it acquaints them with the general principles of preparation of the final thesis, as well as possible ways of doing that, which is interesting. (P35, professional pedagogical SP) I don‘t know if my reflection will reach the teachers and if it does, will they take careful notice of it. My overall impression is that this professional pedagogical study programme on the whole is amazing, and it could get even better if student reflections were included in the programme in subsequent years. (P39, professional pedagogical SP) |

|

|

Personalisation not manifest: what does not work |

Neglecting the needs of |

It should be remembered that the programme includes both humanities and science students, and they will deliver lessons very differently. It often seemed that the programme was more focused on the humanities. (P5, minor SP) Certainly not always efforts were made to turn attention to the interests of students. Rather, we were asked to give our opinions on various aspects, topics for the learning material, etc. (P1, minor SP) Students of this programme have diverse backgrounds. What is easier to understand for linguists, is harder for students from natural sciences, and vice versa. One and the same system does not work for the entire flow of students. Sometimes we saw that teachers were trying to take this into account, yet nonetheless, the tasks were often not suited to natural sciences. (P6, minor SP) Not all students know their interests. Also, not all student interests can be met. (P7, minor SP) |

|

Personalisation not manifest: what does not work |

Theory not married to practice |

All those activities we had during the years of studies did not grow our fur for practice. When we entered training placements, both observer and assistant, it was really scary, nothing clear because we weren’t prepared for such challenges. (P4, minor SP) The studies are short, it would be better to focus on the practical side––the paperwork, bureaucracy, lesson plans, methods, strategies and so on. (P40, professional pedagogical SP) It [personalisation] turned out well, only the focus on theory was a bit excessive because we wanted teachers to show us in practice how things should work, not just in theory. (P41, professional pedagogical SP) It occurred to me that the programme provided too much theoretical knowledge and theories, and there was a lack of practical aspects, practices of application of knowledge such as in fictitiously moderated situations or group activities and projects. Many of those theoretical things are certainly not needed in the daily life of the school and the teacher, whilst practical aspects are sorely needed. Given that the studies are very short, you want efficiency and the skills that the student will then be able to apply successfully in their work as a teacher. (P39, professional pedagogical SP) […] these are theoretical tasks that are not applicable in practice. (P22, minor SP) […] basically, there was so much learning material that we often just ran through. […] The students could read it by themselves and prepare on the sources provided, it would be much more interesting and take on the nature of discussions in which we would review our thoughts on pedagogy and philosophy and tie them to the current reality and practical situations. Most successful were the methods of assessment, but not the content. (P37, professional pedagogical SP) |

|

A template-like nature of activitie |

[…] most of this type of tasks simply fade away from your memory; the format of the activities was somewhat template-like. (P31, minor SP) There was no choice based on student interests other than some activities. […] I would not call personalisation the fact that we would be given literature and asked to prepare from it, or that in some subjects we could use literature we found on our own. I would rather call it self-directed learning because the tasks were much the same for everyone. (P46, professional pedagogical SP) […] the level of people’s knowledge is not taken into account and sometimes taught are self-evident ‘truths’––after all, we are not bachelor students. (P42, professional pedagogical SP) Our contribution to planning was limited to the choice of option rather than creation of something new. (Participant 1, minor SP) |

|

|

The downside or dearth of reflection |

It was helpful as long as it didn’t take too much time. (P32, professional pedagogical SP) I don’t think our feedback affected our teachers in any way. (P26, professional pedagogical SP) It was a little tricky to realise what was so helpful in listening to peer feedback and reflections as this part was sometimes too time consuming. (P34, professional pedagogical SP) Not all theoretical lectures provided an opportunity for reflection. (P29, professional pedagogical SP) To me personally, self-reflection is not a necessary part of learning, but I imagine that teachers may find it interesting to get student feedback and improve the teaching of their subject. (P45, professional pedagogical SP) |

|

|

Personalisation not manifest: what does not work |

Feeling left to your own device |

In some cases, a lot was left to the will of the student and was more akin to throwing a child unable to swim into the water. Saying ‘whatever you will find online’ or providing literature sources that are difficult to access or completely inaccessible during the lockdown is not a very adequate means of promoting student autonomy. (P39, professional pedagogical SP) I would look for everything myself. My autonomy has grown even stronger. (P36, professional pedagogical SP) […] we weren’t framed. On the other hand, it was easy to ‘digress’ in the wrong direction. (P40, professional pedagogical SP) |

|

Personalisation in the making: The dos and don’t |

Turn to the student |

The teacher should ask and discuss everything with students. (P23, minor SP) |

|

Tailor theory to practice |

More trips to schools from the very first days, lectures on training of in-service teachers (before practice placements as well); it is understandable that theory differs from practice, but it is also needed to know how to act in one or another situation. More activities that relate to school students, teachers, relationships between parents and teachers, etc. Also, it would be good to conduct at least one study (!!!!!!) at school (would give the experience needed for writing the final thesis and would also be useful in life). (P4, minor SP) I would suggest paying attention to the following: the teaching itself, its forms could be geared towards what is needed in today’s school. The format of lectures could serve as a template of what we could apply as teachers. It is possible to choose different methods of teaching so it would make more sense––not only to talk about it, but also to apply it in practice. (P20, minor SP) |

|

|

Broaden choic |

[…] choice is always good. Just that there’s a question of whether that was enough. (P18, minor SP) |

The second major theme developed from our data was named personalisation not manifest: what does not work. As the name suggests, this theme carries a negative charge as it captures those experiences of students that point to aspects of learning not conducive of personalisation. This theme was espoused by a markedly smaller number of students than the first and includes five subthemes: neglecting the needs of some students; theory not married to practice; a template-like nature of activities; the downside or dearth of reflection; feeling left to your own devices. The first subtheme, neglecting the needs of some students, emerged from accounts of four students of the minor study programme and suggests that these students did not see personalisation in learning activities which to other students appeared as such. E.g., Participant 1 (minor SP) said: ‘Certainly not always efforts were made to turn attention to the interests of students. Rather, we were asked to give our opinions on various aspects, themes for the learning material, etc.’ In addition, two students said that the programme was geared more towards humanities than natural sciences: ‘Students of this programme have diverse backgrounds. What is easier to understand for linguists, is harder for students from natural sciences, and vice versa. One and the same system does not work for the entire flow of students. Sometimes we saw that teachers were trying to take this into account, yet nonetheless, the tasks were often not suited to natural sciences’ (Participant 6, minor SP).

The second subtheme, theory not married to practice, was endorsed by another six students of both programmes and indicates the inadequate preparation of students for real-life challenges, e.g.: ‘Because all those activities we had during the years of studies did not grow our fur for practice. When we entered training placements, both observer and assistant, it was really scary, nothing clear because we weren’t prepared for such challenges’ (Participant 4, minor SP). Participant 22 (minor SP) notes that ‘[…] these are theoretical tasks that are not applicable in practice’, and Participant 39 (professional pedagogical SP) said: ‘It occurred to me that the programme provided too much theoretical knowledge and theories, and there was a big lack of practical aspects, practices of application of knowledge such as in fictitiously moderated situations or group activities and projects. Many of those theoretical things are certainly not needed in the daily life of the school and the teacher, whilst practical aspects are sorely needed. Given that the studies are very short, you want efficiency and the skills that the student will then be able to apply successfully in their work as a teacher’.

Four students of both programmes saw the negative side of the template-like nature of activities. Participant 8 (minor SP): ‘[…] most of this type of tasks simply fade away from your memory; the format of the activities was somewhat template-like’. ‘Our contribution to planning was limited to the choice of option rather than creation of something new’ (Participant 1, minor SP).

Interestingly, eight students of the professional pedagogical study programme saw the downside or dearth of reflection, although none of the students from the minor study programme envisioned the negative side of such activities. E.g., ‘It was a little tricky to realise what was so helpful in listening to peer feedback and reflections as this part was sometimes too time consuming’ (Participant 34, professional pedagogical SP); ‘To me personally, self-reflection is not a necessary part of learning, but I imagine that teachers may find it interesting to get student feedback and improve the teaching of their subject’ (Participant 45, professional pedagogical SP).

The final subtheme entitled feeling left to your own devices related to experiences of three students of the professional pedagogical study programme and suggests the feeling of inadequate support and supervision on the part of the teachers, although the words of Participant 36 convey the silver lining of such an experience: ‘In some cases, a lot was left to the will of the student and was more akin to throwing a child unable to swim into the water. Saying “whatever you will find online” or providing literature sources that are difficult to access or completely inaccessible during the lockdown is not a very adequate means of promoting student autonomy’ (Participant 39, professional pedagogical SP); ‘I would look for everything myself. My autonomy has grown even stronger’ (Participant 36, professional pedagogical SP).

Personalisation in the making: the dos and don’ts. This third major theme contains three subthemes worded in the imperative: turn to the student; tailor theory to practice and broaden choice. The idea behind the first subtheme, turn to the student, is self-evident and captures the accounts of two students of the minor study programme, one of whom stated the following: ‘I think teachers should pay more attention not so much to the fact that the student is a student who needs to have the material delivered to him, but to see the student as a would-be teacher who should be educated as such and helped in his growth and understanding of students and their interests’ (Participant 9, minor SP).

The subtheme tailor theory to practice was endorsed by six students of the minor study programme who urged developers and teachers of this programme to place more focus on the practical side of teaching how to teach rather than the theory of teaching. ‘We should be taught practical, relevant things, something we can actually use when standing in front of the class’ (Participant 17, minor SP); ‘I think that the teacher should pay attention to what is relevant in the educational system at a given time and what students face during their practice placements at school. This should inform the guidelines for activities and suggest topics. […] All the content of learning could be organised in this way from the beginning of studies’ (Participant 12, minor SP).

The final subtheme in this category, broaden choice, encompasses the quintessence of personalisation and, although directly espoused by only two students of both programmes, leaks through many of the above discussed accounts. As noted by Participant 37 (professional pedagogical SP), who recognises the freedom of choice in their study programme, ‘Of course, the options could be even broader’. And Participant 18 (minor SP) observes that ‘[…] choice is always good. Just that there’s a question of whether that was enough’.

To sum up, the feedback we collected from students of the two teacher education study programmes at Vilnius University on practices of implementation of the personalised learning framework is predominantly positive as most students recognise the presence and benefits of such practices in their studies. There are notable differences in the evaluations of students of the two programmes, e.g., only or mostly students of the minor SP felt that the needs of some students were neglected, saw the negative side of the template-like nature of activities and urged their teachers (and perhaps developers of the programme) to turn to the student and tailor theory to practice, whilst only students of the professional pedagogical SP saw the downside or dearth of reflection and felt left to their own devices. These findings suggest differences in overall visions of the two SPs developed by their users, which might stem from differences in their backgrounds and life experiences: students of the minor SP were significantly younger (Mage= 22 vs Mage= 35, p < .00) and in most cases were enrolled in their first studies, whereas students of the professional pedagogical SP were older on average and had previously completed first, second, or even third cycles of university studies. Hence, it is not surprising that some of them felt a lesser need for reflection (as for them this skill is perhaps automatic and often used without conscious effort) and welcomed more theory (as they are better able to see the benefits of theory and ways in which it informs practice). In contrast, students of the minor SP may need stronger guidance and supervision and might welcome more elaborate explanations of how theory is married to practice.

It must also be noted that paradoxically, the same activities proposed by teachers of the two study programmes were seen by some students as conducive of personalisation in learning and by others as cornering them into forced choices that were perceived as hurdles in their growth as would-be teachers. This and other findings bespeak the complex nature, benefits and setbacks in the phenomenon of personalised learning.

Discussion

The shift from a teaching to a learning paradigm demands a new generation of aspiring teachers who are themselves self-directed learners. To achieve this, teacher education programmes need to prepare student teachers to fully understand and experience the importance and transformative impact of personalised learning (Alisauskiene et al., 2020a).

The new concept of personalised learning developed by partners of the INTERPEARL project embraces four core elements: 1) collaborative dialogue, co-construction, personal reflection, autonomy and mutual ownership by learners and teachers; 2) flexible content, tools and learning environments to facilitate learners’ interests and needs and teacher-learner collaboration; 3) targeted support in response to learner interests and needs; 4) data-driven reflection, decision making and continuous improvement (Alisauskiene et al., 2020b). The results of thematic analysis of students’ reports on the case of implementation of personalised learning practices in two teacher education study programmes at Vilnius University indicate that all the four elements of personalisation are recognised by students of the two programmes. Instances of PL in the modules General Pedagogy and Final Thesis were captured by three major themes: personalisation in vivo: facilitation of growth as a would-be teacher; personalisation not manifest: what does not work; and personalisation in the making: the dos and don’ts. Within each of these themes, students envisioned aspects of PL that were welcomed or missing in their studies, and more vivid and numerous were the accounts which revealed positive experiences with personalisation as captured by the first theme, personalisation in vivo: facilitation of growth as a would-be teacher. This theme includes eight subthemes encompassing the appeal, benefits, diversity, depth, and breadth of personalised learning, which bespeaks the invaluable outcomes it brings to the study process. The second theme, personalisation not manifest: what does not work, carries a negative charge and includes five subthemes capturing the frustrations, downsides, ill manifestations and shallow implementations of personalisation in the study process. Lastly, the third theme, personalisation in the making: the dos and don’ts, contains three subthemes worded in the imperative that inform the developers and users of the study programmes about the practicality and foci of personalisation preferred by our participants.

Our findings suggest that implementation of personalisation is by far not a very smooth and easy undertaking which, although very appealing to students, may carry the inherent risks of granting too much freedom to students who are unprepared or might disrupt the well-established and predictable process of teaching. Swan (2017) provided a literature review which examined various conceptualisations of personalised learning and their effect on students’ learning. The author identified both the benefits and detriments of personalisation to students’ achievements and found ambiguities in the concept and its effects on students’ learning. Notably, several studies reviewed found benefits of personalised learning, which included improved academic performance, fewer behavioural problems, increased motivation and better teacher-student relationships (McGuinness, 2010; Prain et al., 2013; Russell & Riley, 2011, as cited in Swan, 2017). Some studies, however, found negative effects of personalised learning. For example, one study in which personalised learning was defined as ‘the tailoring of pedagogy, curriculum and learning support to meet the needs and aspirations of individual learners, irrespective of ability, culture or social status, in order to nurture the unique talents of every pupil’ (Underwood et al., 2007, p. 57, as cited in Swan, 2017) found that implementing personalised learning in shallow ways of increasing student choice without increasing student agency can increase student disengagement and result in lower achievement in high-performance schools. Increased choice of learning methods correlated negatively with students’ investment in their education, which may be due to poorly motivated learners preferring the predictability and comfort of the predetermined work methods over risk-involving novelties.

Several other researchers also argue that personalisation can be understood and implemented in deep or shallow ways (Bolstad et al., 2012; Campbell et al., 2007; Fullan, 2009). Shallow understandings generally involve increased student choice in activity but do not challenge the teacher-directed nature of the educational system. In contrast, deep personalisation is transformational in that it requires students to take far greater responsibility for their learning and be involved in decision making (Bolstad et al., 2012). The differences between deep and shallow expressions of personalisation are often evident when having conversations with students about their learning. According to Bolstad et al. (2012, p. 19), ‘learners who have had the time, support and opportunities to have input into shaping their learning tend to be better able to describe in their own words what they have come to learn about their strengths, weaknesses, motivations and interests as learners, and how this relates to other contexts of their lives, including their ideas about how they see themselves in the future’.

It must be noted that although all the students in our study welcome elements of personalisation in their teacher education study programmes and such elements support performativity, it appears that personalisation cannot be implemented into university study programmes in its full scope as this would mean tailoring the overall learning content to the needs of individual students and, hence, departing from the general vision of the study programme, its objectives, and foreseeable outcomes. Nonetheless, the student voice needs to be heard so that a seemingly radical, yet optimal change which is unimaginable today becomes feasible in the future. As noted by one student in our study, ‘I don’t know if my reflection will reach the teachers and if it does, will they take careful notice of it. My overall impression is that the professional pedagogical study programme on the whole is amazing, and it could get even better if student reflections were included in the programme in subsequent years’ (Participant 39, professional pedagogical SP).

References

Alisauskiene, S., Kaminskiene, L., Milteniene, L., Meliene, R., Kazlauskiene, A., Rutkiene, A., Venslovaite, V., Kontrimiene, S., & Siriakoviene, A. (2020a). Innovative Teacher Education Through Personalised Learning. Proceedings of ICERI2020 Conference, 2944–2952.

Alisauskiene, S., Guðjónsdóttir, H., Kristinsdóttir, J. V., Connolly, T., O’Mahony, C., Lee, L., Milteniene, L., Meliene, R., Kaminskiene, L., Rutkiene, A., Venslovaite, V., Kontrimiene, S., Kazlauskiene, A., & Wozniczka, A. K. (2020b). Personalized Learning within Teacher Education: A Framework and Guidelines. Current and Critical Issues in Curriculum, Learning, and Assessment, 37, 1–50.

Alisauskiene, S., Kaminskiene, L., Milteniene, L., Meliene, R., Rutkiene, A., Kazlauskiene, A., Siriakoviene, A., Kontrimiene, S., Venslovaite, V., O’Mahony, C., Lee, L. Guðjónsdóttir, H., Kristinsdóttir, J. V., & Wozniczka, A. K. (2021). Innovative teacher education through personalised learning: Designing teaching and learning scenarios. Proceedings of INTED2021 Conference, 5809–5818.

Appleton, K. (1993). Using theory to guide practice: Teaching science from a constructivist perspective. School Science and Mathematics, 93(5), 269–274.

Berge, Z. L. (2011). If you think socialisation in mLearning is difficult, try personalisation. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 5, 231–238.

Bless, H. & Greifeneder, R. (2018). General framework of social cognitive processing. In R. Greifeneder & H. Bless (Eds.), Social Cognition: How Individuals Construct Social Reality (2nd ed.) (pp. 16–42). London: Routledge.

Bolstad, R., Gilbert, J., McDowall, S., Bull, A., Boyd, S., & Hipkins, R. (2012). Supporting future-oriented learning and teaching: A New Zealand perspective. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Council for Educational Research Press. Retrieved from http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/schooling/109306.

Bray, B. & McClaskey, K. (2012). Personalisation vs differentiation vs individualization.

Retrieved from: http://education.ky.gov/school/innov/Documents/BB-KMPersonalised learningchart-2012.pdf.

Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Terry, G. (2015). Thematic analysis. In P. Rohleder & A. Lyons (Eds.), Qualitative research in clinical and health psychology (pp. 95–113). Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Campbell, R. J., Robinson, W., Neelands, J., Hewston, R., & Mazzoli, L. (2007). Personalised learning: Ambiguities in theory and practice. British Journal of Educational Studies, 55(2), 135–154. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2007.00370.x.

Fullan, M. (2009). Breakthrough: deepening pedagogical improvement. In M. Mincu (Ed.), Personalisation of Education in Contexts Policy Critique and Theories of Personal Improvement (pp. 19–26). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Yerevan Ministerial Communiqué. (2015). Retrieved from: https://www.ehea.info/page-ministerial-conference-yerevan-2015.

Herringon, J. & Oliver, R. (2000). An instructional design framework for authentic learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(3), 23–48

Patrick, S., Kennedy, K., & Powell, A. (2013). Mean what you say: Defining and integrating personalised, blended and competency education. Retrieved from The International Association for K–12 Online Learning (iNACOL): https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED561301.pdf.

Piaget, J. (1969). The Mechanisms of Perception. New York: Basic Books.

Piaget, J. (1972). Psychology and Epistemology: Towards a Theory of Knowledge. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Piaget, J. (1974). The Grasp of Consciousness: Action and concept in the young child. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Pogorskiy, E. (2015). Using personalisation to improve the effectiveness of global educational projects. E-Learning and Digital Media, 12(1), 57–67.

Stake, R. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Swan, C. (2017). Personalised Learning: Understandings and Effectiveness in Practice. Journal of Initial Teacher Inquiry, 3, 3–6.

Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. In W. Stainton Rogers & C. Willig (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology (2nd ed.) (pp. 17–37). London: SAGE Publications.

1 The studies by Alisauskiene et al. (2020a, 2020b, 2021) were carried out within the ERASMUS + KA 203 project entitled Innovative Teacher Education through Personalised Learning / INTERPEARL (No 2018-1-LT01-KA203-046979). The project aims to develop, implement, test and transfer innovative practices of personalised learning within teacher education system(s). Project partners: University of Iceland (Iceland), University College Cork (Ireland), Šiauliai University, Vytautas Magnus University and Vilnius University.

2 In contrast, traditional teaching methods focus on assimilation, which is in line with the key principles of positivism, objectivism, and behaviourism. In a traditional classroom, students wait for the teacher to present the correct information (Appleton, 1993), whereby content is broken down into behavioural objectives to be met, skills to be mastered and tests to be evaluated, and actual learning is accomplished through practice, repetition, and reinforcement of correct answers. Students are passive receivers who only strive to complete the activity correctly with little thought of the significance of the task. The result is that students memorise a variety of terms but often cannot apply them to problems or outside experiences because they do not truly understand them.

3 Stake argues for a flexible design and proposes two basic types of case studies, intrinsic and instrumental. ‘For intrinsic case study, case is dominant’ (Stake, 1995, p. 16), namely, the case study is composed to illustrate a unique case, a case that has unusual interest in and of itself and needs to be described and detailed. ‘For instrumental case study, issue is dominant; we start and end with issues dominant’ (ibid.), thus, the intent of the case study is to understand a specific issue, problem, or concern.

4 In direct interpretation we explored the individual accounts of students, trying to pull them apart and put them back together again more meaningfully, a procedure which may be referred to as analysis and synthesis of direct interpretation. We also collated the individual accounts to see how from the whole aggregate issue-relevant meanings emerged (see Stake, 1995).

5 In the deductive approach, the analytic starting point is more ‘top down’––the researcher brings in existing theoretical concepts or theories that provide a foundation for ‘seeing’ the data, for what ‘meanings’ are coded, and for how codes are clustered to develop themes; it also provides the basis for interpretation of the data (Braun, Clarke & Terry, 2015; Terry et al., 2017).