Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2022, vol. 49, pp. 8–22 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2022.49.1

Perspective of Teachers on Their Competencies for Inclusive Education

Dita Nimante

University of Latvia Faculty of Education, Psychology and Art

dita.nimante@lu.lv

Maija Kokare

Jāzeps Vītols Latvian Academy of Music, Department of Music Education

maija.kokare@jvlma.lv

Abstract. The purpose of this paper is to share findings about teachers’ perceived competencies for inclusion based on data gathered from 1590 (N = 1590) teachers representing 69 mainstream schools of Riga municipality using a survey. In answering the research questions on how teachers perceive themselves, if they have the necessary competencies for implementation of inclusive education, and what is missing, the results showed teachers self-reporting that despite the lack of specific qualification for inclusive education, they have the necessary competencies for inclusion. Teachers indicated that they have a slightly higher level of general competence; however, there is room for improvement in both general and specific competencies for inclusive education. Two of the most important specific competencies for inclusive education that they lack are the “implementation of an inclusive and supportive learning process for everybody by differentiating and adapting the curriculum” and a “timely identification of pupils’ difficulties in the learning process.” The findings reveal the challenges, problems, and limitations that would arise in providing high quality inclusive education to meet the needs of all learners. Despite the fact that teachers perceive that they have certain competencies for inclusive education, the majority of teachers do not feel comfortable and confident in practice in the inclusive classroom. Answers to the other research question revealed a connection between teachers’ age, teaching experience, education, and teachers’ perception of general competencies for inclusive education. A connection was revealed between teachers’ age, teaching experience, and teachers’ perception of specific competencies for inclusive education. Based on the results, suggestions for further research and implications for practice are discussed.

Keywords: inclusion, competencies, mainstream teachers, Riga municipality

Mokytojų požiūris į savo inkliuzinio ugdymo kompetencijas

Santrauka. Straipsnio tikslas – pristatyti apklausos apie mokytojų inkliuzijos kompetencijas radinius. Tyrime dalyvavo 1 590 (N = 1 590) mokytojų iš 69 Rygos savivaldybės bendrojo ugdymo mokyklų. Mokytojų savistatų atsakymai į pirmąjį tyrimo klausimą, kaip mokytojai suvokia save, ar turi reikiamų kompetencijų inkliuziniam ugdymui įgyvendinti ir ko tam trūksta, atskleidė, kad mokytojai mano turintys reikiamas inkliuzinio ugdymo kompetencijas, net jei nėra įgiję formalios kvalifikacijos. Mokytojai teigia pasiekę aukštesnį bendrosios kompetencijos lygį, tačiau jiems dar reikia tobulinti tiek bendrąsias, tiek specifines inkliuzinio ugdymo kompetencijas. Labiausiai ugdyti reikėtų dvi specifines inkliuzinio ugdymo kompetencijas, pavadintas „inkliuzinio ir visus palaikančio mokymosi proceso įgyvendinimas diferencijuojant ir pritaikant ugdymo turinį“ bei „savalaikis mokinių sunkumų mokymosi procese nustatymas“. Tyrimo rezultatai atskleidžia iššūkius, problemas ir apribojimus, kurių kyla siekiant, kad inkliuzinis ugdymas būtų aukštos kokybės ir atitiktų visų besimokančiųjų poreikius. Nepaisant to, kad mokytojai mano turintys tam tikrų inkliuzinio ugdymo kompetencijų, dauguma jų nesijaučia patogiai inkliuzinėje klasėje ir nepakankamai savimi pasitiki. Atsakymai į antrąjį tyrimo klausimą atskleidė ryšį tarp mokytojų amžiaus, mokymo patirties, išsilavinimo ir mokytojų nuostatų apie bendrąsias inkliuzinio ugdymo kompetencijas. Remiantis gautais rezultatais, aptariami pasiūlymai tolesniems tyrimams ir implikacijos praktikai.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: inkliuzija, kompetencijos, bendrojo ugdymo mokyklos mokytojai, Rygos savivaldybė.

________

Note: This article has been developed under the framework of Erasmus+ Project “MyHub – a one-stop-shop on inclusion practices, tools, resources, and methods for the pedagogical staff at formal and non-formal educational institutions.” The research has been presented in ECER 2020.

Received: 20/09/2022. Accepted: 10/11/2022

Copyright © Dita Nimante, Maija Kokare, 2022. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Since the policy of education in Latvia declared a move towards inclusive education (Education Development Guidelines, 2014), classes in mainstream schools have become increasingly diverse, and more children with special needs have moved to mainstream schools. Although the inclusion of special needs children in Latvia’s schools has been promoted since 1998, when the Education Law (Izglītības likums, 1997) came into force, the system faces many challenges. One of these challenges is teachers’ competencies to work in an inclusive environment, particularly with special needs children in a mainstream classroom.

Teachers play a key role in the implementation of inclusive education (Van Mieghem, Verschueren, 2020); they are the most important component for the success of inclusive education (Forlin, Chamber, 2011) and the most important agents of change for inclusion and social justice challenges in schools (Pantič, Florian, 2015). To work successfully in an inclusive environment, the teacher should have certain knowledge, skills, and competencies that can be developed during preservice teaching (Nīmante, Repina, 2018). Research indicates that the more training and opportunities in inclusive education, the more possibilities to gain the necessary competencies to become inclusive teachers (Tangen, Beutel, 2017, Monteiro, Kuok, 2019). However, mainstream teachers worldwide indicate that they are not prepared to teach students with special needs (Monteiro, Kuok, 2019).

As the teacher is the main pillar of implementation of inclusive policies in practice (European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education, 2010), the teacher’s competencies to work in an inclusive environment can either promote or delay the inclusion processes in mainstream schools. Integrating the principles of inclusive pedagogy (Florian, Beaton, 2018) into a teacher’s daily professional life to promote each child’s learning can be quite a challenge for teachers who are already established in their professional field and have long ago received their initial training. Therefore, current research is focused on mainstream teacher’s perception of their competencies for inclusive education and is conducted in Riga’s municipality. This research is important both in the nationwide (Latvian) and local (Riga city) context, as it continues the research carried out so far on the competencies required of teachers for inclusive education (Rubene, Daniela, 2015, Rozenfelde, 2016, Raščevska, Nīmante, 2017, Nīmante, 2018, Nīmante, Repina, 2018, Bethere, Neimane, Ušča, 2016). The teacher Professional Standard (Profesijas standarts, 2018) includes defined competencies that a teacher should perform in the context of inclusive education. As it has been indicated before, there is a clear need for mainstream teachers to further develop their professional skills related to inclusive education (Bethere, Neimane, Ušča, 2016). It is important for the city of Riga to understand the specific needs of teachers’ professional development to promote inclusive education in the Riga city schools to provide effective continuous professional learning programs.

The research questions are:

RQ1. How do teachers perceive their competencies for the implementation of inclusive education? What is lacking?

RQ2. What is the connection between teachers’ age, teaching experience, and education related to inclusive education and teachers’ perceptions of their competencies?

This paper covers a part of the research project “Inclusion in Riga City,” which was carried out from January to December 2019, in cooperation with Riga City Municipality and EDURIO Ltd.

Theoretical background

The complexity of an inclusive classroom requires teachers to have diverse competencies to promote successful learning and the well-being of all children. In the inclusive classroom, teachers have to deal with the daily challenges related to children’s educational needs by ensuring high quality learning and the personal growth of every child, including those who have special needs. As Kershner admitted, “inclusion can be particularly challenging for understanding the knowledge associated with teachers’ individual and collective activity in schools because of the diverse set of opinions, values and skills operating in a system of limited financial and human resources” (Kershner 2007, 491). Consequently, inclusive teaching requires more than just a traditional approach to teaching. A positive attitude towards inclusive education is a precursor for teachers to be more open to inclusive education and include children with special needs in their classroom (Sharma, Aiello, 2018). Competency is a broad term, which can be defined as skills, knowledge, attitudes, and the ability to perform an action in specific professional situations. Thus, competencies for inclusion signify that a teacher must possess certain skills, knowledge, and attitude to be able to work in an inclusive classroom successfully. An earlier research project “Teacher Education for Inclusion” came up with several teacher competencies for inclusive education: valuing learner diversity, supporting all students, cooperation with others, continuing personal and professional development (European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education, 2012, 7). Besides generic professional competency, inclusive classrooms require specific competencies from teachers, such as implementing lessons for diverse learners and flexible scheduling (Dingle, Falvey, 2014). Important skills for implementing inclusion in the classroom are described as adaptations of the curriculum: adapting curricular goals and instructional materials, behavior management, identifying special needs, modifying content, and using effective questioning (Kuyini, Yeboah, 2016). This is in line with the research done by Majoko (Majoko, 2019), who examined perceptions of special needs education teachers about the key competencies required from mainstream teachers for inclusive education. Majoko comes up with the following list of competencies: screening and assessment, differentiation of instruction, classroom and behavior management, collaboration. The research indicates that teachers with better knowledge about special needs feel more competent to embrace inclusive education for special needs children (Low, Lee, 2019). An inclusive school case study carried out in Latvia (Nīmante, 2018) suggests that teachers’ perception of both general and specific competencies for working in an inclusive environment are important. Several specific competencies for inclusive education were mentioned: a good understanding of an inclusive (diverse) classroom, all children’s learning needs and disorders; ability to solve inclusive education’s ethical dilemmas; knowledge in special pedagogy, modification of the program for children with special needs. General competencies must be applied by teachers in a new, inclusive context too, which would include intensive collaboration with other teachers, child assistants, and special teachers both inside and outside the classroom. Pantič and Florin (2015) admit that teacher competencies act as agents of inclusion and social justice, which involve working collaboratively with others and thinking systematically about ways of transforming practices, schools, and systems.

Methodology

Through the cooperation between the University of Latvia and the Riga City Council Department of Education, Culture, and Sports, a questionnaire (consisting of 108 questions) for teachers based on literature review and discussions with practitioners was developed and finalized by incorporating opinions of the representatives of Riga municipality. Teachers working at Riga’s municipality schools were surveyed using the EDURIO tool (edurio.com), which is easily accessible for every teacher in Riga’s municipality. Primary data processing methods (for descriptive statistics) and secondary data processing methods (for inferential statistics) were implemented using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 22.0) for analysis. Methods of descriptive statistics, the Kruskal–Wallis Test, and Kendall rank correlation were used for the statistical analysis of data obtained in this study.

The questionnaire includes different kind of data – general education and teaching experience and experience in inclusive education in particular, as well as questions related to understanding inclusive education, teachers’ attitudes towards an inclusive classroom, teachers’ personal characteristics for inclusive education, teachers knowledge, skills, and competencies for inclusive education, teachers’ professional and personal confidence and comfort when working in an inclusive classroom with pupils with special needs, and the expected support.

This paper analyzes the data on education, age, teaching experience in general and inclusive education experience in particular, teachers’ perception of the necessary competencies for inclusive education and partially on personal comfort and confidence when working in an inclusive classroom.

Respondents were asked to evaluate both teacher’s professional generic and specific competencies required for inclusive education on a 7-point scale (from 1 – poor to 7 – excellent, Cronbach’s α = 0.939). Teachers were then asked to identify which (0 to 3) of the 12 competencies they need to develop the most (however, some respondents identified more than 3 competencies for development, and these answers are included in the analysis as well).

The following general competencies which hold an important part in inclusive education were included in the questionnaire:

GC1 – continuous learning by learning new methods and techniques;

GC2 – taking on leadership in the learning process and outside the classroom by supporting other colleagues and collaborating;

GC3 – deliberately seeking help if necessary and listening to advice;

GC4 – acting emotionally intelligently in everyday and non-standard situations.

The following specific competencies for inclusive education were included in the questionnaire:

SC5 – timely identifying pupils’ difficulties in the learning process;

SC6 – implementing an inclusive and supportive learning process for everybody by differentiating and adapting the curriculum;

SC7 – adapting support for children with special needs;

SC8 – collecting and interpreting data for identifying pupils’ difficulties in the learning process;

SC9 – developing possible recommendations for an Individual Learning Plan in the subject based on collected data about a pupil’s strong points and weaknesses;

SC10 – based on the data collected, evaluating the effectiveness of the adapted curriculum and support measures provided to the pupil with special needs in the subject;

SC11 – collaborating with specialists in the support team to develop an Individual Learning Plan in the subject for the pupil with special needs;

SC12 – collaborating with the support team, other teachers, and parents whose child has special needs.

Finally, teachers were asked to respond to the statement on how comfortable and confident they feel working in an inclusive classroom. There were three possible answers provided.

Participants

The participants were asked to fill out a questionnaire by Education, Culture and Sports Department of the Riga City Council. A letter to all Riga’s schools was electronically shared. Participation was voluntary. The questionnaire complies with the EU’s data protection regulation. In total, 1614 (n=1614) completed questionnaires were received from teachers; however, 1590 (n = 1590) were analysed. The questioner included information about respondents age, education, teaching experience and competencies to work in an inclusive classroom. Teachers representing 69 schools of Riga municipality (primary and secondary schools) responded to the survey. The largest group of participants, comprising 42% of the respondents, work with pupils from 5th to 9th grades (ages 12–16).

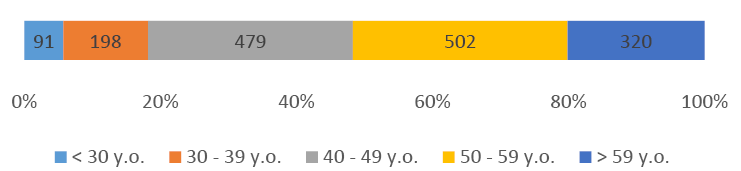

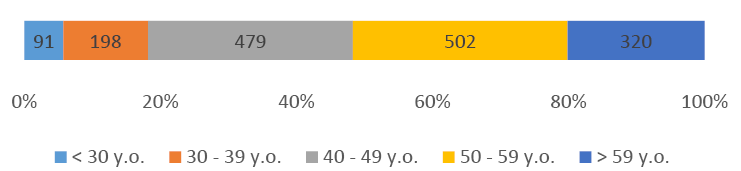

Most of the teachers were in the age group between 40 to 59 (See Figure 1). The average age was 49.4, which reflects the general situation in Latvia (OECD, 2018).

Figure 1. Distribution of respondents by age groups

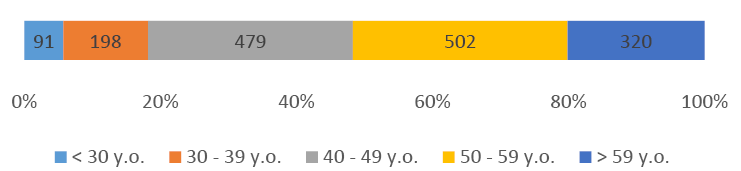

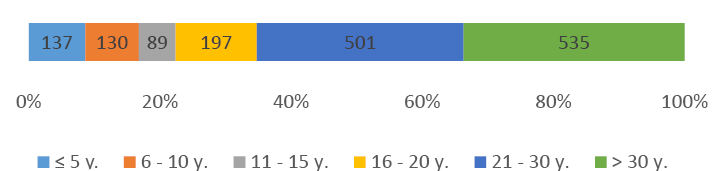

Consequently, most teachers have more than 21 years of teaching experience (see Figure 2). The average amount of teaching experience amounted to 25.1 years.

Figure 2. Respondents’ teaching experience

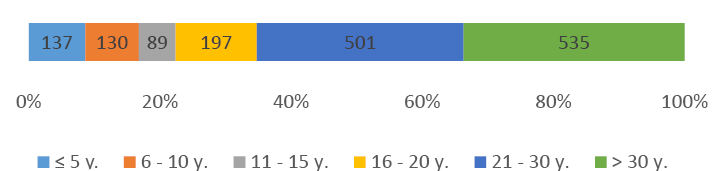

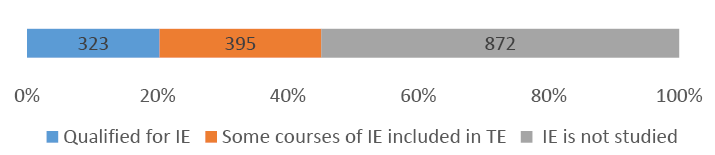

The question on teacher education in relation to inclusive education was also included in the survey. The data reveals that a few teachers have qualification in inclusive education, and some admitted that they have attended a short course (for example, a 36-hour continuous professional development course) on inclusive education. The majority admitted that they do not have any education related to inclusive education (see Figure 3). These results coincide with the results of a previous study in Latvia (Raščevska, Nīmante, 2017) stating that the majority of teachers lack the necessary education for inclusive education.

Figure 3. Teacher education for inclusive education

Results and discussion

In this section, the research findings are presented based on research questions, followed by a discussion.

RQ1. How do teachers perceive their competencies for the implementation of inclusive education? What is lacking?

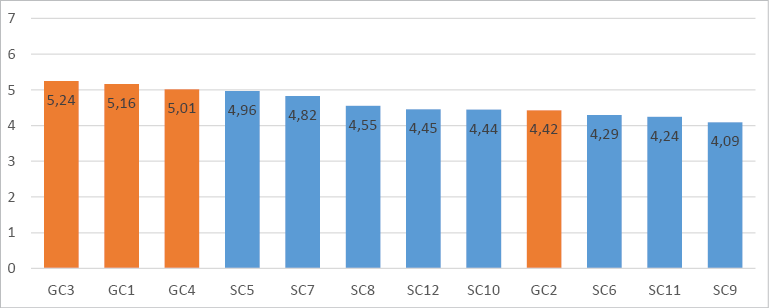

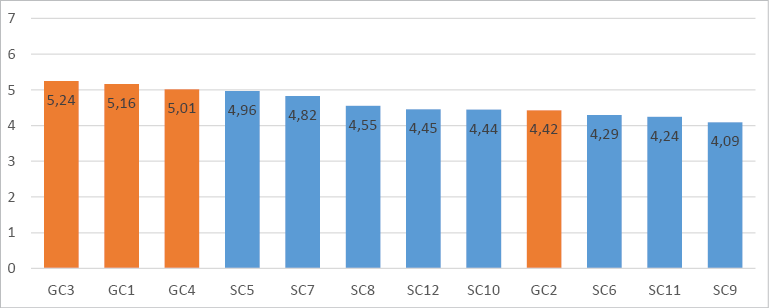

Teachers have self-reported that they have the necessary competencies for inclusion; however, there is room for improvement in both general and specific competencies for inclusive education. Teachers’ self-assessment has a relatively higher level of competencies in the so-called general competencies (GC) compared to the so-called special competencies (SC) for inclusive education (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Teacher self-reported competencies for inclusive education

The results confirm previous research, that despite the lack of specific qualification and education for inclusive education, teachers perceive their competence for inclusive education as quite satisfactory (Raščevska, Nīmante, 2017).

Besides, for two of the competencies – GC2 (taking on leadership in the learning process and outside the classroom by supporting other colleagues and collaborating) and GC4 (acting emotionally intelligently in everyday and non-standard situations) – the distribution across the groups of teaching experience is the same.

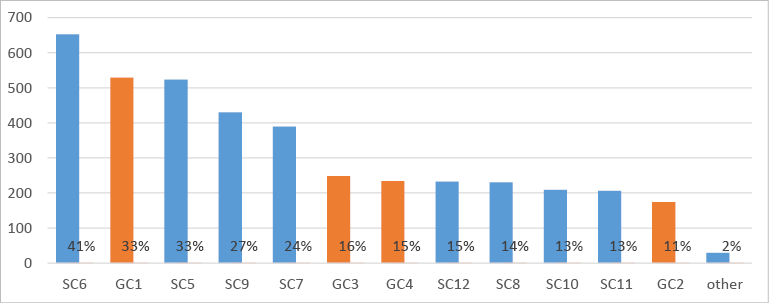

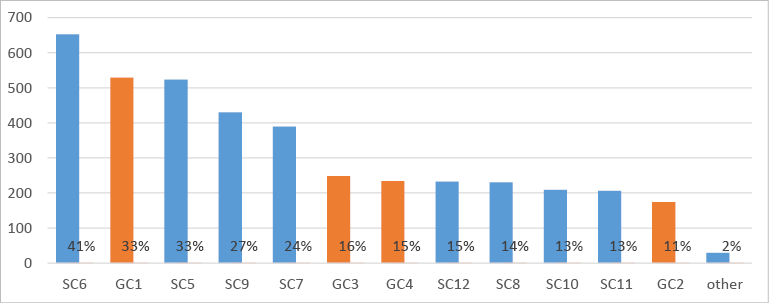

To determine which of the competencies teachers should develop the most, 4085 statements for identified competencies are analyzed, displaying a proportion of respondents who chose the particular competence to be developed the most (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Competencies for inclusive education that should be developed the most

Teachers acknowledged five competencies most needed and lacking in inclusive education: SC6 (implementing an inclusive and supportive learning process for everybody by differentiating and adapting the curriculum); GC1 (continuous learning by learning new methods and techniques); SC5 (timely identification of pupils’ difficulties in the learning process); SC9 (developing possible recommendations for an Individual Learning Plan in the subject based on collected data about the pupil’s strong points and weaknesses); and SC7 (adapting support for children with special needs).

To “implement an inclusive and supportive learning process for everybody by differentiating and adapting the curriculum” is admitted by teachers as the most needed and lacking competence. Classroom teachers’ ability to adapt curriculum or instruction and differentiate is one of the most important factors and a prerequisite for the implementation of inclusive education in the classroom (Deng, Wang, 2017). The “Report on ‘inclusive education in European schools’” (2018) made by Schola Europaea suggested that European schools place particular emphasis on differentiated teaching that takes account of individual differences in learning style, interest, motivation, and aptitude, so that every child in the classroom can reach their highest potential. Thus, the importance of organizing a supportive learning environment for everybody (not exclusively children with special needs) in an inclusive classroom is perceived by teachers as the most important and at the same time as the most lacking competence. Second, there is “the timely identification pupils’ difficulties in the learning process.” These findings coincide with a previous study (Raščevska, Nīmante, 2018). The specific competencies, such as SC9 and SC7, are connected to providing support to children with special needs in an inclusive classroom. Consequently, teachers feel that they lack those specific competencies, as they do not have the necessary competencies in special education (Bethere, Neimane, Ušča, 2016).

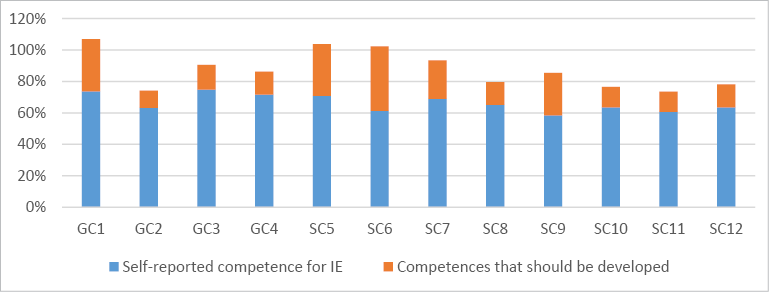

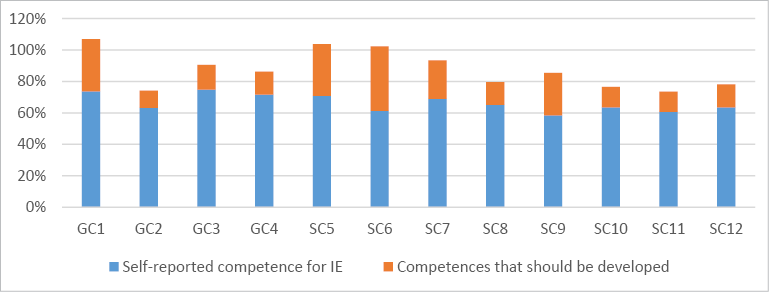

Evaluating the average values of teachers’ self-reported competencies in relation to the identified competencies that should be developed (see Figure 6), it could be concluded that teachers recognize GC1, SC5, and SC6 as the most important for their work in an inclusive classroom (GC1, SC5, and SC6 are both relatively highly self-reported).

Figure 6. Average values of teachers’ self-reported competencies in relation to the identified competencies that should be developed for inclusive education

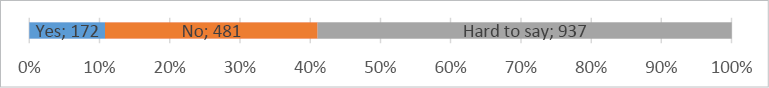

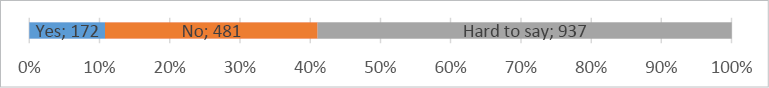

Analyzing the data on the teachers’ responses on how comfortable and confident they feel working in an inclusive classroom in practice, overall, the majority of respondents (89%) did not feel comfortable and confident working in an inclusive classroom – only a small part (11%) felt comfortable and confident to do that. By analyzing the data, it was concluded that 30% of the respondents categorically did not feel comfortable and confident, but 59% were doubtful and unable to answer this question clearly, as they have chosen the response “hard to say” (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. How comfortable teachers feel working in an inclusive classroom

Such data reveals a contradiction that, on the one hand, the teachers proclaim a satisfactory level of competencies for inclusive education and practice, but on the other – they lack confidence and feel uncomfortable implementing inclusive education in practice. Furthermore, the distribution of answers does not differ in groups with different experiences in inclusive education (Kruskal-Wallis test, p <0.05). This may indicate that inclusive education is an equally new practice, which can be very challenging for all teachers, regardless of age and experience.

When looking at the second research question (RQ2) of “What is the connection between teachers’ age, teaching experience, and education related to inclusive education and teachers’ perceptions of their competencies?”, it was revealed that there are differences between results relating to specific and generic competencies.

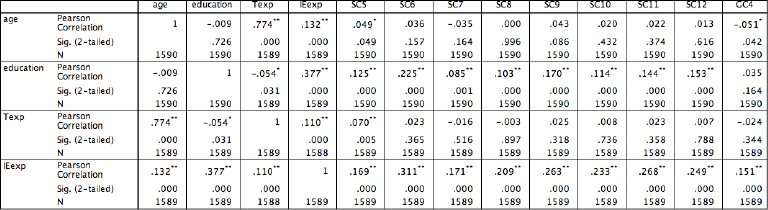

Results related to specific competencies for inclusive education reveal that there are some differences related to age groups, teaching experience in general and inclusive education in particular, as well as to education related to inclusive education (See Figure 8).

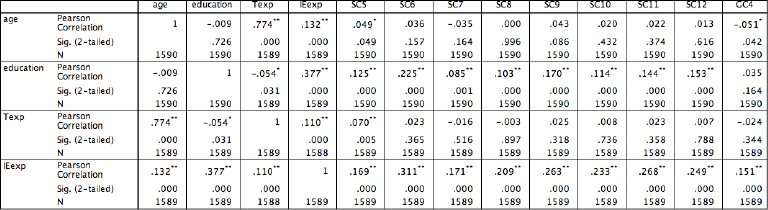

Figure 7. Correlation between teachers’ self-reported specific competencies for IE and age, teaching experience in general and IE and education related to inclusive education

A part of specific competencies for inclusive education significantly (p < 0.05) differs across the age groups (Kruskal-Wallis Test) – SC5, SC7, SC8, SC9. Nevertheless, other competencies – SC6, SC10, SC11, SC12 – do not reveal age-dependent differences. Part of specific competencies (SC5; SC7; SC8; SC9) are related specifically to including children with special needs into mainstream class. Specific competencies (SC6; SC10 ; SC11; SC12) are related both to specific competencies for including children with special needs into regular classes and specific competencies for insuring inclusive pedagogy for everyone in the classroom.

Only SC5 significantly (p < 0.05), but not strongly (r = 0.049), correlates with age (older teachers self-reflect a somewhat higher competence SC5). Regarding teaching experience, SC5 and SC6 significantly (p < 0.05) differ across the groups, but only SC5 significantly (p < 0.01), but not strongly (r = 0.07), correlates with work experience (more experienced teachers pointed out that they have a higher competence SC5). All specific competencies for inclusive education significantly (p < 0.05) differ across education groups and more or less strongly correlate with education related to inclusive education and teaching experience (see Figure 7). The results partly correspond with a previous study in Latvia. The study by Bethere, Neimane, and Ušča confirmed that the highest self-evaluation of diagnostic competencies (in our study SC5 – the timely identification pupils’ difficulties in the learning process) was possessed by teachers with work experience of 16–20 years (Bethere, Neimane, Ušča, 2016).

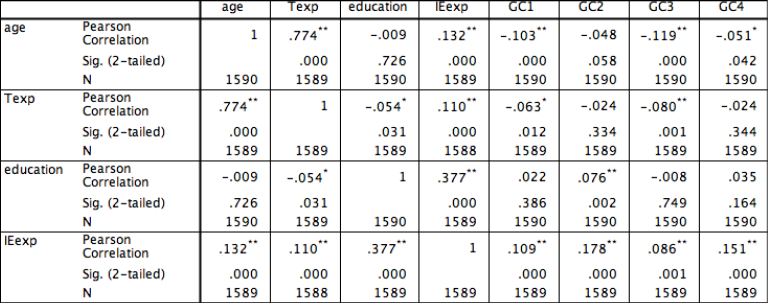

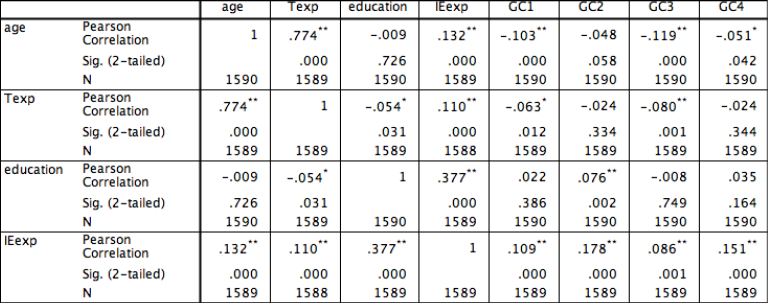

Results related to general teacher competencies reveal that there are some differences related to age groups, general teaching experience, experience in inclusive education, as well as education related to inclusive education (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Correlation between teachers’ self-reported general competencies for IE and age, teaching experience in general, and IE and education related to inclusive education

GC1, GC2, and GC3 significantly (p < 0.05) differ across the age groups. GC1 and GC3 significantly (p < 0.01) but not strongly (r = -0.103 and r = -0.119) correlate with age (younger teachers pointed out that they have a little higher competencies GC1 and GC3). GC4 significantly (p < 0.05) but not strongly (r = 0.05) correlates with age (younger teachers pointed out a higher competence GC4).

Regarding the general teaching experience, GC1 and GC3 significantly (p < 0.05) differ across the groups. GC1 significantly (p < 0.05), but not strongly (r = -0.063) correlate with teaching experience (less experienced teachers self-reflect little higher competence GC1 and GC3 significantly (p < 0.01) but do not correlate strongly (r = -0.08) with general teaching experience (teachers with less general teaching experience pointed out a little higher competence GC3). These results can be explained by the natural disposition of younger teachers, who perceive themselves as constantly learning new methods, techniques (GC1), deliberately seeking help, and listening to advice if necessary (GC3).

All general competencies (CG1, CG2, CG3, CG4) self-reported by teachers significantly (p < 0.05) positively correlate (0.086 < r < 0.178) with the teaching experience in inclusive education (more experienced teachers pointed out a little higher level of competence).

Conclusions

Although inclusive education is formally declared in the educational policy of Latvia, this study reveals that one of the most important challenges for the implementation of inclusive education is the teacher’s ability to implement those policies in practice. Teachers’ insufficient competence for implementing inclusive education can have serious setbacks for the successful development of inclusive practices.

In answering the first research questions “How do teachers perceive their competencies for the implementation of inclusive education? What is lacking?”, we can conclude that teachers have self-reported that they have the necessary competencies for inclusion despite the lack of specific qualification and education for inclusive education. Although teachers perceive that their generic competencies are slightly higher than specific competencies, there is room for improvement in both generic and specific competencies for inclusive education. Two of the most important specific competencies for inclusive education that teachers lack is “implementation of an inclusive and supportive learning process for everybody by differentiating and adapting the curriculum” and “the timely identification pupils’ difficulties in the learning process.” The most important and missing general competence is “continuous learning, by learning new methods, techniques.” Despite that teachers perceived themselves as having certain competencies for inclusive education, the majority of teachers do not feel comfortable and confident in an inclusive classroom; consequently, it raises questions about their insufficient ability to implement those competencies in practice. This contradiction hinders the possibility of a successful implementation of inclusive education, which would offer pupils with special educational needs the opportunities for adequate learning.

In answering the second research question, “What is the connection between teachers’ age, teaching experience, and education related to inclusive education and teachers’ perceptions of their competencies?”, it can be concluded that teachers’ perceptions of certain specific competencies related to including children with special needs into mainstream classes (in particular the timely identification of pupils with special needs) are related to teachers’ age and teaching experience. Older teachers with more teaching experience indicate that they have higher perceived specific competencies for inclusive education. Results also revealed that those teachers who have had formal education for inclusive education perceive higher competencies.

Considering those results, we can conclude that there is a need for targeted professional development for teachers. These professional development programs should include not only the development of general competencies of teachers, but more fully target those specific competencies for inclusive education.

For a teacher to work in an inclusive environment, which is very complex and challenging, there is a need for professional development (Movkebaieva, Oralkanova, 2013, Loreman 2014, Monteiro, Kuok, 2019), helping teachers acquire both general and specific competencies. The implementation of inclusive education requires teachers to reconsider their teaching practices, so professional development should support teachers by providing good practice. Teachers must be provided with the necessary tools and support to face the challenges of an inclusive classroom. Research indicates that purposefully orientated professional development courses can develop specific competencies for inclusive education (Bhroin, King, 2020), but inadequate teacher preparation can become a barrier for inclusive education (Sharma, Armstrong, 2019). The necessity for teacher’s professional development has been highlighted before in Latvia (Bethere, Neimane, Ušča, 2016), but current research results provide guidance for the content of professional development programmes for teachers for inclusive education. Research concludes that teacher education programmes for inclusion should consist of practicum models to practice inclusive pedagogy in a safe and supportive environment (Savolainen, Malinen, 2020). It could be important both for pre-service and in-service teachers.

The research findings raise intriguing directions for future studies:

1) Gathering more evidence on the way how specific competencies for inclusive education are developed in current teacher continuous professional education for inclusive education;

2) Finding out the results of professional program development on inclusive education for teachers, by including in those programs both general and specific competencies as learning outcomes, to assess the results of the implementation of those programs;

3) Continuing with a longitudinal study to assess the situation in Riga municipality.

References

Bethere, D., Neimane, I., Ušča, S. (2016). The opportunities of teachers’ further education model improvement in the context of inclusive education reform. 2nd International Conference on Lifelong Education and Leadership for ALL, Proceedings, Liepāja University: Liepāja, 288- 298.

Bhroin, O.N. & King, F. (2020). Teacher education for inclusive education: a framework for developing collaboration for the inclusion of students with support plans. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(1): 38-63. Doi: 10.1080/02619768.2019.1691993

Deng, M., Wang, S., Guan, W. & Wang, Y. (2017). The development and initial validation of a questionnaire of inclusive teachers’ competency for meeting special educational needs in regular classrooms in China. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21 (4), 416-427. Doi: 10.1080/13603116.2016.1197326

Dingle, M., Falvey, M. A., Givner, C. C., Haager, D. (2014). Essential Special and General Education Teacher Competencies for Preparing Teachers for Inclusive Settings. In Issues in Teacher Education, 13 (1). Retrieved from: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ796426.pdf

Education Development Guidelines [Izglītības attīstības pamatnostādnes] (2014).

European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education. (2012). Teacher Education for Inclusion Profile of Inclusive teachers. Watkins, A., ed. Retrieved from: http://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/teacher-educationfor-inclusion_Profile-of-Inclusive-Teachers.pdf

Florian, L.& Beaton, M. (2018). Inclusive pedagogy in action: getting it right for every child. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22 (8), 870-884. Doi:4876/10.1080/13603116.2017.1412513.

Florian, L.& Linklater, H. (2010). Preparing teachers for inclusive education: using inclusive pedagogy to enhance teaching and learning for all. Cambridge Journal of Education, 40 (4), 369-386. Doi: 4876/10.1080/0305764X.2010.526588

Forlin, C.& Chambers, D. (2011). Teacher preparation for inclusive education: increasing knowledge but raising concerns. In Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39 (1), 17-32. Doi:4876/10.1080/1359866X.2010.540850

Izglītības likums [Education Law] (1997). Saeima: Rīga. Retrieved from: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/50759-izglitibas-likums

Kershner, R. (2007). What do teachers need to know about meeting special educational needs?” In The SAGE Handbook of Special Education, edited by L. Florian, London: Sage Publications, 486- 498, 580.

Kuyini, A. B., Yeboah, K. A., Das, A. K., Alhassan, A. M. & Mangope, B. (2016). Ghanaian teachers: competencies perceived as important for inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20 (10), 1009-1023.

Loreman, T. (2014). Measuring Inclusive Education Outcomes in Alberta. Canada. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18 (5), 459–483. Doi:10.1080/13603116.2013.788223.

Low, H. M., Lee, L. W.& Ahmad, A., C. (2019). Knowledge and Attitudes of Special Education Teachers Towards the Inclusion of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. Doi: 4876/10.1080/1034912X.2019.1626005

Majoko, T. (2019). Teacher Key Competencies for Inclusive Education: Tapping Pragmatic Realities of Zimbabwean Special Needs Education Teachers. Sage Open, Vol. 9 (1), doi: 10.1177/2158244018823455

Monteiro, E., Kuok, A.C.H., Ana M. Correia, A.M., Forlin, C.& Teixeira, V. (2019). Perceived efficacy of teachers in Macao and their alacrity to engage with inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, Inclusive Education in the Asia Indo-Pacific Region, 23 (1), 93-108. Doi: 4876/10.1080/13603116.2018.1514762

Movkebaieva, Z., Oralkanova, I., & Uaidullakyzy, E. (2013). The Professional Competence of Teachers in Inclusive Education. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273852635_The_Professional_Competence_of_Teachers_in_Inclusive_Education [accessed Jun 09 2020].

Nīmante, D. (2018). Competent Teacher for Inclusive Education: What Does it Mean for Latvia?// In Innovations, Technologies and Research in Education (Ed. Daniela, L.), UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, 229-244. 362. URL:https://www.cambridgescholars.com/innovations-technologies-and-research-in-education

Nīmante, D.& Repina, N. (2018). Inclusive education for pre- service teachers in Latvia - what are the learning outcomes for pre-service teachers? 11th annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (ICERI), Dates: 12-14 November, 2018, Seville, Spain: Proceedings, Ed. L. Gómez Chova, A. López Martínez, I. Candel Torres, Seville: IATED Academy. Doi: 10.21125/iceri.2018.2452, ISBN: 9788409059485, ISSN: 2340-1095, 6209-6215.

OECD (2018). Kas ir mūsdienu direktori, skolotāji un skolēni. I sējums: Skolotāji un skolu vadītāji – pilnveide visa mūža garumā [Who are today’s principals, teachers and students. Volume I: Teachers and school leaders - lifelong development]. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/education/talis/TALIS2018_CN_LVA_lv.pdf

Pantić, N.& Florian, L. (2015). Developing teachers as agents of inclusion and social justice. Education Inquiry, Special Issue: Teacher Education Policies and Developments in Europe, Volume 6 (3). Doi: 4876/10.3402/edui.v6.27311

Profesijas standarts (2018). IZM: Rīga. Retrieved from: https://visc.gov.lv/profizglitiba/dokumenti/standarti/2017/PS-048.pdf

Raščevska, M., Nīmante, D., Umbraško, S., Šūmane, I. Martinsone, B.& Žukovska, I. (2017). Pētījums par bērniem ar speciālām vajadzībām sniedzamo atbalsta pakalpojumu izmaksu modeli iekļaujošas izglītības īstenošanas kontekstā [A study of the cost model of support services for children with special needs in the context of the implementation of inclusive education]. Retrieved from: http://www.izm.gov.lv/images/izglitiba_visp/IZMiepirkumamLUPPMFgalaparskats08122017.pdf

Report on ‘inclusive education in the European schools (2018). Schola Europaea: Brussels. Retrieved from: https://www.eursc.eu/Documents/2018-09-D-28-en-4.pdf

Rozenfelde, M. (2016). Skolēnu ar speciālajām vajadzībām iekļaušanas vispārējās izglītības iestādēs atbalsta sistēma, Promocijas darbs doktora zinātniskā grāda iegūšanai pedagoģijā, speciālajā pedagoģijā [System of Inclusion of Students with Special Needs in General Education Institutions, Doctoral Thesis for Doctoral Degree in Pedagogy, Special Pedagogy] R: Latvijas Universitāte. Retrieved from: http://dspace.lu.lv/dspace/bitstream/handle/7/32003/298-55964-Rozenfelde_Marite_mr16007.pdf?sequence=1

Savolainen, H., Malinen, O. P. & Schwab, S. (2020). Teacher efficacy predicts teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion – a longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. International Journal of Inclusive Education, Latest Articles. Doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1752826

Sharma, U, Armstrong, A.C., Merumeru, L., Simi, J. & Yared, H. (2019). Addressing barriers to implementing inclusive education in the Pacific. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23 (1), 65–78.

Sharma, U., Aiello, P., Pace, E.M., Round, P.& Subban, P.(2018). In-service teachers’ attitudes, concerns, efficacy and intentions to teach in inclusive classrooms: an international comparison of Australian and Italian teachers. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33 (3), 437–446. Doi: 10.1080/08856257.2017.1361139

Tangen, D.& Beutel, D. (2017). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of self as inclusive educators. International Journal of Inclusive Education, Vol. 21 (1), 63-72. Doi: 4876/10.1080/13603116.2016.1184327

Van Mieghem, A., Verschueren, K., Petry K.& Struyf, E. (2020). An analysis of research on inclusive education: a systematic search and meta review. Journal International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24 (6), 675-689. Doi: 4876/10.1080/13603116.2018.1482012