Socialinė teorija, empirija, politika ir praktika ISSN 1648-2425 eISSN 2345-0266

2023, vol. 26, pp. 60–68 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/STEPP.2023.5

The Welfare State: The Challenges of Sustainability

Stein Kuhnle

University of Bergen, Norway

Stein.Kuhnle@uib.no

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3048-8620

Summary. It is nothing new that ‘the welfare state’ faces serious challenges. Ever since the 1970s, Western welfare states have by many researchers been regarded as being in crisis, but despite many policy adjustments and important variations among Western welfare states, the overall scope of the welfare state, as measured by social expenditure per capita, has by and large increased. At the same time, we can observe a globalization of social policy and the emergence of a more active social role of the state in many parts of the world during recent decades.

But new challenges due to a variety of new security issues and new dimensions of uncertainty have appeared, not least following the unanticipated Russian large-scale invasion of and war on Ukraine and concomitant international political developments. Political unease about the future of the welfare state and scope of social policies in different parts of the world has escalated. Welfare political priorities must compete with increased priorities for defense, cyber security, and issues related to energy, climate, food, and the environment.

Motivations for state responsibility for citizen welfare and well-being – as well as for the type and scope of responsibility - vary. The fate of the welfare state and social policies is clearly a question of political and normative commitment to what kind of socially active state is desired. The paper addresses the following topics: Why should a state be socially active? What were historical reasons for developing welfare states? What are current motivations for developing and maintaining welfare states? What are the economic, political, and moral dimensions of welfare state sustainability? In addition to possible national political responses to social challenges, it is argued that in a globalized world reinforced international cooperation, coordination and regulation may be necessary to achieve sustainability of (national) welfare states.

Keywords: Welfare states, challenges, sustainability, universal rights, social protection

Received: 2023-11-10. Accepted: 2023-11-16.

Copyright © 2023 Stein Kuhnle. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

The concept of the welfare state

‘The welfare state’ is most generally defined as a form of government in which the state through legislation takes on the responsibility of protecting and promoting the basic well-being of all its members. The scope and generosity of this responsibility varies over time and across states, as do the definition of or operationalization of ‘well-being’. Likewise, the specification of ‘member’ of society or the state can vary as to whether it refers to all residents or those holding national citizenship only. The concept or conception of ‘the welfare state’ has become increasingly applied in comparative social and health policy research over the last three decades, and the identification of different developmental paths and different welfare state models have become important elements of this research, especially since the Danish sociologist Gösta Esping-Andersen’s path-breaking study of three worlds of welfare capitalism in 1990 (Esping-Andersen, 1990). Numerous handbook publications in recent years also attest to the growing attention to and academic and political interest in studies of ‘the welfare state’ and its multifariousness (e.g., The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State, 2010/2021; The Routledge Handbook of the Welfare State, 2019; The Routledge International Handbook to Welfare State Systems, 2017; Handbook on East Asian Social Policy, 2013; Handbook of Social Policy and Development, 2020; Handbook on Austerity, Populism and the Welfare State, 2021; The Routledge Handbook of Scandinavian Politics, 2018). However, the concept of ‘the welfare state’ is not part of everyday language worldwide, and it carries different connotations in different national contexts, e.g., widely used and with a positive connotation in Europe, hardly used, and mostly with a negative connotation, in the USA, and barely used at all in China.

A variety of ‘welfare state models’

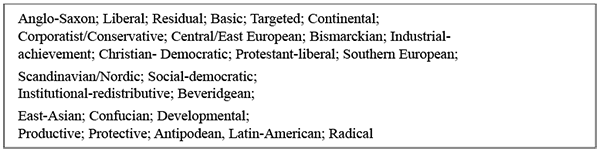

Given different conceptions of welfare and the role and scope of government, of needs covered, population coverage, financing, organization, regulation, eligibility, benefit levels and differentiation, etc., researchers have conceptualized different ‘models’ of welfare states. Until the 1990s this was typically a Western-oriented approach, both in terms of the base of researchers and of empirical focus, but studies with a global focus emerged and grew rapidly since the late 1990s. A list of new concepts and labels demonstrate this, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Concepts and labels of welfare state models: Examples from the literature

Why a socially active state?

States have become socially active for various reasons and motivations. Historically, in the 19th century, early initiatives for state actions were spurred by the existence and identification of old and new social risks such as widespread poverty, industrialization, capitalism, urbanization, contagious diseases, state leaders’ motive to maintain regime stability, aspiration for state- and nation-building and social integration, and democratic mobilization from below for social protection and improvement of social conditions. Different motivations for social policies could lead to similar policy outcome, and similar motivations for social policies could result in different policies. There is no one-to-one-to-one relationship between observations of problems, motivations for political action, and contents of policy decisions. During the last 100–120 years social policies have expanded in many ways and for new needs and reasons due to demographic concerns, recognition of social rights, class compromises, motivation to promote economic productivity and social investment, reconciliation of work and family life, and aim of equalizing life chances.

Welfare states come in different forms and sizes

A basic distinction between welfare states concerns the combination of three different principles for welfare provision (cash benefits and/or benefits-in-kind):

(1) The principle of need (targeting; economic means-testing; residualism)

(2) The principle of merit (social insurance; reciprocity; ‘deservedness’; ‘contract’)

(3) The principle of ‘citizenship’/residence (universalism; ‘social right’)

All welfare states are based on a combination of these principles, but with different patterns, different emphasis on the each of the principles. Based on comparative studies one hypothesis would be that a welfare state which primarily relies on the principle of universalism is probably more conducive both to redistribution and limited poverty and more resilient – and sustainable – in times of crises than a welfare state primarily building on the principle of means-testing and/or principle of merit. Universal programs acknowledge that we are all stakeholders, that we are all at risk, and that we are all potential or actual beneficiaries.

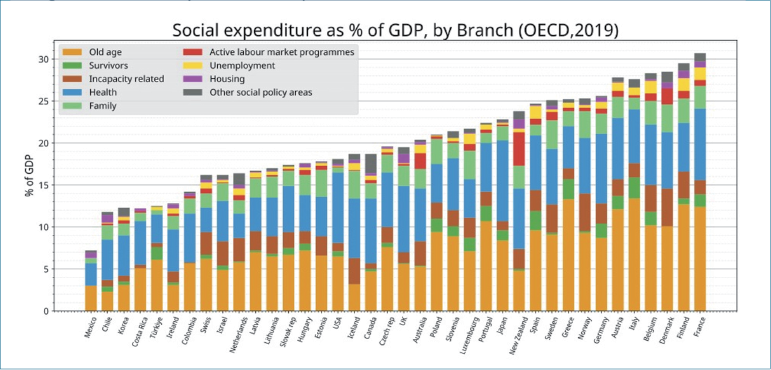

Whatever the form of welfare state or ‘model’ and despite much focus on neoliberal policies in many countries and concern about the sustainability of the welfare state during recent decades, the overall scope of the welfare state has been stable or expanding in OECD countries as measured by social expenditure as percent of GDP as illustrated in Figure 2. The breakdown of expenditures also shows that expenditure for old age pensions and health services dominate everywhere and given trends of demographic change these policy areas indicate the biggest challenges for sustainability.

Beyond the OECD countries we can observe trends underpinning the welfare role of the state. There has been growth of conditional cash transfer programs – a social policy innovation of the South, emanating from Brazil and Latin America to assist poor, vulnerable families with children and promote child education and health. Furthermore, health care services are becoming more universal in terms of population coverage and a variety of noncontributory social pensions has been introduced in countries with dual labor markets and high rates of informality (UN, 2018). But importantly: it must be noted that as of now as many as more than half of the world population lacks basic social protection (UNEN, 2021).

Figure 2. Social expenditure as percent of GDP in OECD countries in 2019

Times of uncertainty: old and new

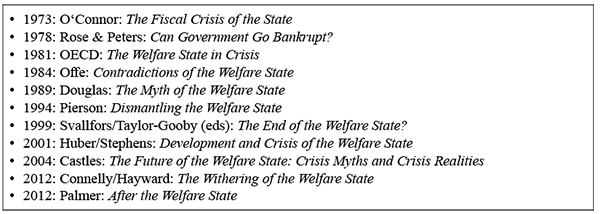

Uncertainty about the status and future of the welfare state is nothing new. That (Western) welfare states are considered to be in crisis or are moving towards a crisis is a recurring topic in the research literature. A selection of book titles during the last 50 years demonstrates this, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. A selection of book titles indicating a dark or ‘pessimistic’ perspective on the future of the welfare state

Other studies have advanced a brighter picture of long-term welfare state development (e.g., Glennerster 2010, Kuhnle 2000) indicating that assessing status and prospects is also a question of time perspective and welfare state dimensions and characteristics examined.

But agreement can possibly be reached on the general assessment that the circumstances in which welfare states first arose and developed and the circumstances in which they operate today are very different. Demographic change and international business cycles require constant reconstruction work on the welfare state.

Crucial new uncertainties have emerged during the recent two-three years. A global ‘polycrisis’ is looming due to the Covid-pandemic and its consequences, due to Russia’s invasion of and war on Ukraine, refugee crises, disrupted supply chains, high inflation, energy and food insecurity, debt crises, climate-induced natural disasters and increased geopolitical rivalry and mistrust. The polycrisis has a collateral impact on the politics of welfare and add to uncertainty and challenges to the sustainability of established welfare states and to the further development of welfare states in emerging economies.

Uncertainty and dimensions of welfare state sustainability

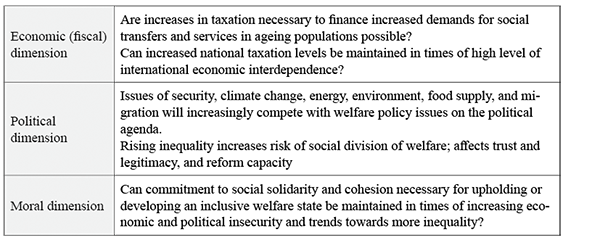

Following Glennerster (2010) old and new uncertainties can be said to relate to three dimensions of welfare state sustainability: economic, political and moral. Each of the three dimensions gives rise to several intriguing questions and issues, some of which are summed up in Figure 4.

We can imagine several possible impacts of economic globalization or international economic integration and competition on national welfare states. Is, as often assumed, international economic integration a threat to the national welfare state? To this, three contesting hypotheses can be formulated:

(1) Maybe: High levels of state provision of social welfare are not considered sustainable (“efficiency hypothesis”);

(2) Hardly: Welfare states compensate for the risks that accompany economic openness (“compensation hypothesis”);

(3) No: Political potential for greater international consensus on taxation to prevent ‘a race to the bottom’ (“the welfare state itself globalizes”)

Figure 4. Old and new uncertainties relate to three dimensions of welfare state sustainability (building on Howard Glennerster, 2010)

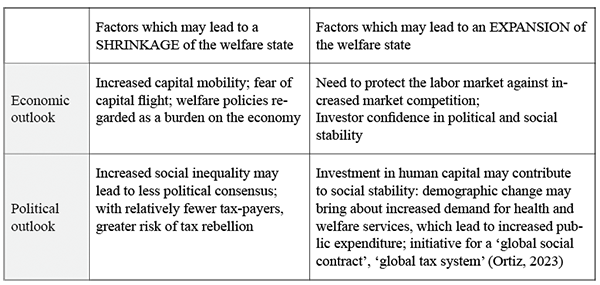

In Figure 5 an overview is presented of tentative economic and political factors which in a more global economy may lead to either an increased pressure on the welfare state leading to a shrinkage of the welfare state and factors which may lead to an expansion of the welfare state. The overview of pro- and con-arguments for possible welfare state sustainability or development is presented to illustrate that alternative scenarios can be outlined very much dependent on assumptions about decisions and choices made by political actors, organized interests, firms, voters and consumers.

Dealing with uncertainty: Any hope?

We can observe that:

• There is not one recipe for welfare state maintenance given varieties of welfare state ‘models’ and variations in economic and political conditions and capacities for development. National goals for social policies diverge. Uncertainties and prospects vary;

• Old European welfare states persevere despite crises, cutbacks and trimming of social programs; some deconstruction, but also reconstruction and (new) construction;

• Innovative policy solutions emerge in developing countries;

• There has been a massive growth of international epistemic communities and comparative welfare research over the last 30 years, not least since the drive for global social policy perspectives (initiated by Deacon, Hulse and Stubbs, 1997).

Figure 5. Economic and political factors which in a more globalized economy may lead to a shrinkage or expansion of the welfare state

A global universal right to social protection?

A global universal right to social protection and security is an idea which has gained increasing significance in the course of recent decades parallel to the growth of international organizations, “transnational actors,” and international epistemic communities, e.g.:

• ILO: Social security for all (2012)

• WHO: Health for all (1978)

• UNESCO: Education for all

• UN: Universal health care (2012)

• UN: 2030 Agenda for sustainable development (2015)

• World Bank & ILO: Global partnership for universal social protection to achieve the sustainable development goals (2016)

It can be noted that ideas for a global minimum tax have been suggested by the Nobel laureate in economics Joseph Stiglitz (2021): “The international community seems to be moving towards a historic agreement on the taxation of multinational corporations, hoping to end the race to the bottom by imposing a global minimum tax. At their meeting in Rome, the G20 leaders endorsed the underlying framework created under the auspices of the OECD,” and Isabel Ortiz (2023) has suggested that “a global social contract is urgently needed: anchored in human rights, with higher social standards and better social services, to ensure universal coverage with adequate benefits in education, health, social security or social protection and other public services.”

Beyond the national welfare state: how to get there?

Uncertainties and challenges have accumulated at national levels during the recent two-three years. This state of affairs, plus markedly increased political polarization in the world, makes it for the time being even more difficult to imagine much progress on initiatives for coordinated global social action. We face a truly collective action problem. There can be little doubt that prospects for welfare state sustainability at national levels are conditioned by international political developments. The pervasiveness of international labor and capital mobility, migration, contagious diseases, and climate change in the world all require more international regulation and rules about rights to social protection and welfare. The future sustainability of national welfare states is hardly conceivable without strengthened international cooperation. International cooperation can be recognized as an additional political dimension of the sustainability of welfare states at the national level.

References

Castles, Francis G., 2004. The Future of the Welfare State: Crisis Myths and Crisis Realities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Connelly, James, and Hayward, Jack, 2012. The Withering of the Welfare State. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Deacon, Bob, Hulse, Michelle, and Stubbs, Paul, 1997. Global Social Policy: International Organizations and the Future of Welfare. London: Sage.

Douglas, Jack D., 1989. The Myth of the Welfare State. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Esping-Andersen, Gösta, 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge & Princeton, NJ: Polity & Princeton University Press.

Glennerster, Howard, 2010. The Sustainability of Western Welfare States, in The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State (1st ed.). Oxford: OUP.

Handbook on Austerity, Populism and the Welfare State, 2021. Ed. Bent Greve. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Handbook on East Asian Social Policy, 2013. Ed. Misa Izuhara. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Handbook of Social Policy and Development, 2020. Eds. James Midgley, Rebecca Surender, and Laura Alfers. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Huber, Evelyn, and Stephens, John D., 2001. Development and Crisis of the Welfare State: Parties and Policies in Global Markets. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

ILO, 2012. Social security for all. Building social protection floors and comprehensive social security systems. The strategy of the International Labour Organization. Geneva: ILO.

Kuhnle, Stein (ed.), 2000. Survival of the European Welfare State. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

O’Connor, James, 1973. The Fiscal Crisis of the State. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

OECD, 1981. The Welfare State in Crisis. Paris: OECD.

OECD, 2019. Social Expenditure Database: https://www.oecd.org/social/expenditure.htm

Offe, Claus, 1984. Contradictions of the Welfare State. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ortiz, Isabel, 2023. Global social policy in perspective, in Paul Stubbs (Ed.), Global Social Policy at 25: Reflections and Prospects. Zagreb: The Institute of Economics.

Palmer, Tom. G., 2012. After the Welfare State. Sydney: Centre for Independent Studies.

Pierson, Paul, 1994. Dismantling the Welfare State? Reagan, Thatcher, and the Politics of Retrenchment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rose, Richard and Peters, Guy, 1978. Can Government Go Bankrupt? New York: Basic Books.

Stiglitz, Joseph, 2021. Making the international corporate tax system work for all, in Foundation for European Progressive Studies (3 November).

Svallfors, Stefan and Taylor-Gooby, Peter, 1999. The End of the Welfare State? Responses to State Retrenchment. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State, 2010 (1st ed.). Eds. Francis G. Castles, Stephan Leibfried, Jane Lewis, Herbert Obinger, and Christopher Pierson. Oxford: OUP.

The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State, 2021 (2nd ed.). Eds. Daniel Béland, Kimberly J. Morgan, Herbert Obinger, and Christopher Pierson. Oxford: OUP.

The Routledge Handbook of the Welfare State, 2019 (2nd ed.). Ed. Bent Greve. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

The Routledge International Handbook to Welfare State Systems, 2017. Ed. Christian Aspalter. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

The Routledge Handbook of Scandinavian Politics, 2018. Ed. Peter Nedergaard and Anders Wivel. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

UN, 2012. General Assembly resolution on Universal Health Coverage (https://www.un.org/en/observances/universal-health-coverage-day#:~:text=On%2012%20December%202012%2C%20the,to%20quality%2C%20affordable%20health%20care.)

UN, 2015. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (https://sdgs.un.org/goals)

UN, 2018. Social protection and social progress (https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2018/07/Chapter-ISocial-protection-and-social-progress.pdf)

UNEN, 2021. Thematic Brief Social Protection (https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021/04/a-tb_on_social_protection.pdf)

UNESCO, 2015. Education for all 2000-2015: Achievements and challenges (https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232565)

WHO, 1978. Declaration of Alma-Ata, International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12. September (https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/almaata-declaration-en.pdf?sfvrsn=7b3c2167_2)

World Bank and ILO, 2016. Global partnership for universal social protection to achieve the sustainable development goals (https://www.social-protection.org/gimi/gess/NewYork.action?id=34)