Information & Media eISSN 2783-6207

2024, vol. 99, pp. 85–105 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2024.99.5

Between a Burden and Green Technology: Rishi Sunak’s Framing of Climate Change Discourse on Facebook and X (Twitter)

Oleksandr Kapranov

NLA University College, Norway

Abstract. The issue of climate change has been one of the critical foci of political discourse worldwide (Wagner, 2023). Given that political debates and political discourse are quite often communicated on Social Networking Sites (SNSs), for instance, Facebook and X (Araújo & Prior, 2021), it appears highly relevant to tap into political actors’ discourse on SNSs that addresses the issue of climate change. Guided by the importance of SNSs in political discourse on climate change, the present article introduces and discusses a study on how Rishi Sunak, the current prime minister of the United Kingdom (the UK), frames the issue of climate change on his official Facebook and X accounts. Specifically, the aim of the study was to identify the types of frames used in Sunak’s climate change discourse in a corpus of his posts on Facebook and X. The corpus was collected and analysed in accordance with the methodology proposed and developed by Entman (2007). The results of the analysis revealed that Sunak’s framing of climate change involved a pragmatic economy-oriented aspect, which was presented discursively by imparting it a personalised dimension that involved multimodality. In particular, it was discovered that Sunak frequently framed the issue of climate change via the frames Burden and Green Technology. The findings were discussed in conjunction with the prior research on framing in climate change discourse.

Keywords: climate change; British political discourse; Facebook; frame; framing; X (Twitter)

Tarp naštos ir žaliosios technologijos: Rishi Sunako klimato kaitos diskursas „Facebook“ ir X („Twitter“) socialiniuose tinkluose

Santrauka. Klimato kaitos klausimas yra vienas svarbiausių politinio diskurso židinių visame pasaulyje (Wagner, 2023). Atsižvelgiant į tai, kad politiniai debatai ir politinis diskursas gana dažnai perduodami socialinių tinklų svetainėse, pavyzdžiui, „Facebook“ ir X (Araújo ir Prior, 2021), atrodo labai aktualu pasitelkti politinių veikėjų diskursą socialiniuose tinkluose, kuriame aptariamas klimato kaitos klausimas. Vadovaujantis socialinių tinklų svarba politiniame diskurse apie klimato kaitą, šiame straipsnyje pristatomas ir aptariamas tyrimas, kaip dabartinis Jungtinės Karalystės (JK) ministras pirmininkas Rishi Sunakas savo oficialiose „Facebook“ ir X paskyrose formuluoja klimato kaitos klausimą. Konkrečiai, tyrimo tikslas buvo nustatyti R. Sunako klimato kaitos diskurse naudojamų diskursų tipus jo pranešimuose „Facebook“ ir X paskyrose. Pranešimai buvo renkami ir analizuojami pagal Entmano (2007) pasiūlytą ir išplėtotą metodiką. Analizės rezultatai atskleidė, kad R. Sunako klimato kaitos įrėminimas apėmė pragmatinį, į ekonomiką orientuotą aspektą, kuris diskursyviai buvo pateikiamas suteikiant jam asmeninį aspektą, apimantį multimodalumą. Visų pirma, buvo nustatyta, kad R. Sunakas klimato kaitos klausimą dažnai įrėmino vartodamas terminus „našta“ ir „žaliosios technologijos“. Gauti rezultatai buvo aptarti kartu su ankstesniais klimato kaitos diskurso įrėminimo tyrimais.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: klimato kaita, Didžiosios Britanijos politinis diskursas, Facebook, įrėminimas, X (Twitter).

Received: 2024-01-26. Accepted: 2024-04-25.

Copyright © 2024 Oleksandr Kapranov. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Climate change has become a contentious issue both internationally and domestically, for instance, in the United Kingdom (Chen et al., 2023). Particularly, in the United Kingdom (the UK) the issue of climate change is addressed by a variety of political and societal actors, who, quite often, appear to express polarised opinions concerning the topics of anthropogenic climate change, global warming, and climate change mitigation (Falkenberg et al., 2022). It can safely be posited that the issue of climate change in the UK is both contentious and highly politicised (Nightingale, 2017). Subsequently, it seems of uttermost importance to take stock of what British political actors, for instance, the prime minister, say about climate change and how they say it (Boykoff, 2008). In this regard, it is crucial to note that political discourse in general and politicians’ discourse on climate change in particular have increasingly been communicated on Social Networking Sites (SNSs), such as Facebook and X, which is formerly known as Twitter (Elías-Zambrano et al., 2019). The contention is further emphasised by the literature that points to the pervasive nature of SNSs in climate change discourse by political actors in the UK as well as on the international arena (Pielke Jr & Ritchie, 2021). Taking into consideration the role of SNSs as a critical instrument in climate change communication (Rousseau, 2023), it seems pertinent to uncover how British politicians and, specifically, British prime ministers frame the issue of climate change on SNSs, for instance, on Facebook and X.

Whilst there is a sufficient bulk of literature on British prime ministers’ attitudes towards climate change (Gillings & Dayrell, 2023), little research is available on the current British prime minister’s (i.e., Rishi Sunak’s) position vis-à-vis climate change (Bomberg, 2023). Furthermore, there are no published studies that report on Rishi Sunak’s framing of the issue of climate change on his official accounts on such SNSs, as Facebook and X. In light of the lack of current research, the present study aims to undertake a framing analysis of a corpus of status updates concerning the issue of climate change posted by Rishi Sunak on Facebook and X. Given that framing is routinely employed in scientific analyses of various types of discourses, inclusive of media and political discourse (Entman, 1993; Ophir et al., 2023), framing forms a methodological cornerstone of the present study. According to the canonical definition of framing by Entman (2010a, p. 391), framing presupposes selecting several aspects of reality and connecting them in a particularly focussed narrative in order to define a problem, specify its causes, convey moral assessments, and offer possible remedies.

Informed by (i) Entman’s (2010a) definition of framing and (ii) the critical role of SNSs in political discourse (Araújo & Prior, 2021; Elías-Zambrano et al., 2019), the study attempts to provide answers to the following research questions (RQs):

RQ 1: What types of frames are utilised in Rishi Sunak’s discourse on climate change on his official Facebook and X accounts?

RQ 2: What are the most frequently used frames in Rishi Sunak’s discourse on climate change on his official Facebook and X accounts?

Whilst the RQs focus on the UK political discourse on climate change, they, nevertheless, may offer an invaluable insight into the research problem that is relevant not only to British scholars and lay public, but to the international readership. The novelty of the study consists in generating new knowledge about Rishi Sunak’s framing of climate change. The importance of the study rests with the consideration of the UK’s role in climate change mitigation, which continues even after Brexit, when the UK is not a member of the EU anymore. Indeed, the UK’s role in formulating climate change policies is considered a pioneering one (Bulkeley & Schroeder, 2008), given that the UK has been one of the first countries that recognised the severity of climate change-related problems and proposed concrete, feasible measures in order to mitigate them (Taylor et al., 2014). Hence, British political discourse on climate change policies and climate change mitigation makes the UK and, specifically, British prime ministers, an optimal candidate for the framing analysis (Harcourt, 2020).

Another novel facet of the study involves its international outreach, which is manifested by generating empirical data and extending the existing body of knowledge seen from a broader theoretical perspective on framing, which is relevant to both British and international political actors. For instance, the findings generated by the present study may offer a benchmark for further comparisons of how the issue of climate change is framed in other European non-EU countries as well as in non-European countries that are members of the British Commonwealth. Additionally, the present study can contribute to framing analysis more generally by shedding light on Rishi Sunak’s framing of climate change on SNSs, which these days are considered a universal medium in climate change communication (Son & Jun, 2024).

Having indicated the RQs and the novel aspects of the study, the article proceeds as follows. First, the major tenets of climate change policies in the UK are outlined. Second, a review of the literature on framing in climate change discourse in the UK is provided. Thereafter, I describe the corpus of the study, its methodology, results and their discussion. Finally, the article concludes with the summary of the major findings.

Setting the Scene: Climate Change Policies in the UK

The literature indicates that climate change is treated by the political mainstream in the UK as a science-informed issue (Porter et al., 2015). In this regard, the literature postulates that climate change policies in the UK are, largely, based upon the findings of climate change science (Bowen & Rydge, 2011), which has been one of the driving forces behind the British policies of mitigating the negative consequences of anthropogenic climate change (Johnston & Deeming, 2016). As a means of climate change mitigation, the UK has introduced and, subsequently, implemented measures to reduce CO2 emissions to zero by 2050 (Johnston & Deeming, 2016). It should be noted that “net zero” is defined as the drastic reduction of CO2 emissions in the atmosphere (Booth, 2023).

Presently, net zero is often mentioned in British political discourse on the issue of climate change (Paterson, 2021; Van Coppenolle et al., 2023). The practical measures of achieving net zero involve the introduction and adaptation of legislative acts associated with a more extensive use of renewable energy sources and other measures of climate change mitigation (Johnston & Deeming, 2016; Porter et al., 2015). To date, the British government has introduced multiple statutory acts, initiatives, and services, whose aims are to facilitate the adaptation of the British political actors to the demands and obligations associated with net zero (Webb & van der Horst, 2021). Notably, a substantial bulk of British net zero-related activities are coordinated with the European Union, even though the UK is no longer its part (Youngs & Lazard, 2023).

In summary, it is argued that net zero has become an intrinsic part of British politics on the local and international levels (Gregory & Geels, 2024). Furthermore, it can be posited that the issue of climate change has gained currency in British political discourse (Meckling & Allan, 2020). Currently, however, little is known about Rishi Sunak’s discourse on climate change. Prior to proceeding to the study that attempts to shed light on how he frames his climate change-related discourse, it seems reasonable, however, to outline the literature on framing in climate change discourse in the UK.

Framing in Climate Change Discourse in the UK: Literature Review

Nowadays, framing has gained acceptance as a methodological means of analysing a broad variety of discourses, inclusive of climate change discourse (Almiron et al., 2020; Araújo & Prior, 2021; Kapranov, 2018; Ophir et al., 2023; Scheufele, 2017). There is a widely accepted contention in the literature that the value of framing as a means of discourse analysis rests with casting light on (i) how a certain phenomenon, for instance, a political issue or public controversy is communicated to the public at large discursively, (ii) how the phenomenon is perceived by the public, and (iii) how the discursive representations of the phenomenon influence the public in terms of their choices and behaviour (Entman et al., 2009; Ophir et al., 2023; Tankard Jr, 2001). In this regard, it is posited that “framing is an approach that emphasises certain attributes of an issue over others and as a consequence shape how that issue is understood” (Badullovich et al., 2020, p. 1).

Given that the issue of climate change is still far from being perceived unequivocally by the public at large, as well as political actors, it is critically important to ascertain how they frame climate change through the desirable lenses (De Boer et al., 2010). In light of the aforementioned considerations, the framing of climate change in the UK has attracted attention of a considerable number of researchers, who investigate, mostly, political and media types of discourse (Gillings & Dayrell, 2023). Let us briefly review research on framing the issue of climate change in the UK by focusing on a number of fairly recent studies published within the timeframe of five years from 2018 to 2023.

In the research literature, we may distinguish several themes that underlie a considerable bulk of studies on framing the issue of climate change by British (i) corporate actors (Ferns & Amaeshi, 2021; Jaworska, 2018; Kapranov, 2018; Kristiansen et al., 2021; Nyberg et al., 2022), (ii) mass media (Batziou, 2022; Gillings & Dayrell, 2023; Guenther et al., 2022; Ruiu et al., 2023; Stoddart et al., 2023), (iii) political circles (Almiron et al., 2020; Carter et al., 2018; Gavin, 2018; Hess & Renner, 2019; Lockwood, 2018), and (iv) societal actors (Bevan et al., 2020; de Moor, 2022; Whitmarsh & Capstick, 2018). Let us consider an outline of the literature in conjunction with the aforementioned research themes, starting with the first one, namely British corporate actors’ framing of the issue of climate change.

The research theme that explores the framing of climate change by the major British corporate actors seems to focus, first of all, on fossil fuel corporations (Jaworska, 2018; Kapranov, 2018). Given that the British fossil fuel giants, for instance, British Petroleum (BP), are considered one of the major contributors to CO2 emissions, the literature emphasises that it is of paramount importance to take heed of how they frame the issue of climate change. Recent research (Jaworska, 2018) posits that climate change is rarely framed by the British fossil fuel corporations as the notions of global warming or greenhouse effects. Instead, a more frequent use of the term ‘climate change’ is suggestive of the British fossil fuel corporations’ preference for framing the issue of climate change as a fairly distant phenomenon and not an urgent problem to be mitigated (Jaworska, 2018). This finding is further supported by the literature, which has established that Shell, a British multinational fossil fuel corporation, does not frame its discourse on climate change as a threat by opting to frame it via a rather generic metaphor “Challenge” (Kapranov, 2018). In other words, British fossil fuel corporations, such as BP and Shell, exhibit a trend of distancing themselves from the issue by discursive means, which involve the framing of climate change as a part of corporate social responsibility that, however, downplays the urgency of its mitigation. The research theme that involves the framing of climate change discourse by the British corporations could be summarised to revolve around the stakeholders’ engagement in climate risk mitigation and corporate responsibility (Ferns & Amaeshi, 2021; Kristiansen et al., 2021; Nyberg et al., 2022).

The research theme that focuses on the framing of climate change by British mass media has been pioneered in seminal publications by Boykoff (2008), Carvalho and Burgess (2005), and Carvalho (2010). In their wake, a score of more recent studies published from 2018 to 2023 continue to probe into the framing of climate change by mass media outlets in the UK (Batziou, 2022; Gillings & Dayrell, 2023; Guenther et al., 2022; Ruiu et al., 2023; Stoddart et al., 2023). Just like a decade ago (see Carvalho 2010), the contemporaneous British mass media actors demonstrate a lingering sense of scepticism as far as the framing of climate change is concerned (Ruiu et al., 2023). This contention, however, is in contrast to a number of recent studies, which reason that British mass media outlets’ framing of climate change has evolved from denialism and scepticism to the current foci on (i) sustainable solutions in climate change mitigation and (ii) climate change-related awareness, which seems to correlate substantially with the shift to a more objective opinion on the matter by the general public (Batziou, 2022; Gillings & Dayrell, 2023; Guenther et al., 2022; Stoddart et al., 2023).

It should be observed that the framing of climate change by British mass media is typically accompanied by multimodality. In particular, the literature (Batziou, 2022; Gillings & Dayrell, 2023; Guenther et al., 2022; Ruiu et al., 2023; Stoddart et al., 2023) indicates that British mass media outlets, mostly newspapers and journals, quite routinely utilise the combination of text and photos in covering the issue of climate change. In addition, the framing of climate change by British online media outlets is characterised by a substantial bulk of multimodality that is represented by videos, hyperlinks, and hashtags (Rathnayake & Suthers, 2023).

The research theme that investigates how British political circles frame their discourse on climate change is represented by recent publications that point out to the role played by Brexit in discourse on climate change (Almiron et al., 2020; Gavin, 2018). Specifically, the literature focuses on how Brexit has highlighted a polyphonic dimension in British political discourse on climate change that is framed along the attitudinal and partisan lines (Almiron et al., 2020; Gavin, 2018). In particular, Gavin (2018) as well as Lockwood (2018) indicate that there is a multitude of discursive voices on the British political arena whose negative framing of the issue of climate change correlates with an equally negative framing of the EU and a positive framing of the right-wing political spectrum, which is represented, inter alia, by the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP). Additionally, it should be appreciated that the major political parties in the UK appear to frame their discourse on climate change rather similarly, despite the seemingly strong political divide between them (Carter et al., 2018; Hess & Renner, 2019). To clarify the point, it is argued in the literature that the leaders of the Conservative and Labour parties, respectively, resort to metaphorising their climate change discourse by a rather overlapping set of metaphors, such as “Climate Change as a Journey,” “Climate Change as a Threat,” and “Climate Change as a Challenge” (Kapranov, 2018), which are profusely involved in the framing of the issue.

Finally, let us outline the research theme that explores the framing of climate change by British societal actors. It should be noted that this research field appears to be less extensively investigated in contrast with the literature on the British political actors and mass media. However, there are a number of studies, which reveal the societal perceptions of climate change in the UK (Bevan et al., 2020; de Moor, 2022). Supposedly, they range from postapocalyptic framings that are associated with unavoidable climate disruptions (de Moor, 2022) to scepticism concerning the origine as well as the scope of climate change (de Moor, 2022). Given a heterogeneity of the British societal actors’ perception of climate change, the literature posits that the members of the UK public perceive climate change via a series of cognitive, affective and behavioural frames. It is inferred from the literature that the frames, in addition to the postapocalyptic ones (de Moore, 2022), involve (i) individual engagement in the issue of climate change and (ii) reductions in greenhouse gases and carbon dependency (Whitmarsh & Capstick, 2018).

Among the research themes that have been summarised so far, it appears that there are no state-of-the-art studies that shed light onto the framing of climate change by the current British prime minister, Rishi Sunak. Seeking to narrow the gap in the literature, the subsequent section of the article introduces and discusses a framing investigation that looks into Rishi Sunak’s discourse on climate change.

The Present Study

Given that framing is (i) amply used in a substantial number of studies on climate change discourse in the UK (see the preceding part of the article) and (ii) extensively utilised in research on political discourse on SNSs (Araújo & Prior, 2021; Elías-Zambrano et al., 2019; Ophir et al., 2023), the present study looks into the framing of climate change discourse on Facebook and X by the current British prime minister, Rishi Sunak. In addition to the RQs, which are provided in the introductory part of the article, the study involves the following research tasks: (i) to collect a corpus of Rishi Sunak’s discourse on the issue of climate change on the SNSs Facebook and X, respectively; (ii) to analyse the corpus qualitatively in order to establish the type of frames associated with his climate change discourse; (iii) to quantify Rishi Sunak’s frames in order to establish the most frequently used ones; (iv) to juxtapose the-to-be-identified frames with the prior studies on framing in political discourse; and (v) to identify the types of multimedia (e.g., photos) that are employed in Rishi Sunak’s framing of climate change on Facebook and X.

Following the RQs and the research tasks, the study sets out to collect a corpus of Sunak’s status updates on Facebook and tweets on X on the matter of climate change. It should be specified that the study does not seek to compare possible differences between Sunak’s discourse on climate change on Facebook on the one hand and X on the other hand. On the contrary, his discourse on climate change on these two SNSs is analysed collectively in the body of the corpus. Such an approach to treat Sunak’s Facebook updates and X tweets seems to be justified by the fact that both of his Facebook and X accounts are managed by the prime minister’s (PM’s) digital communications team (www.gov.uk, 2024). The team utilises Facebook to highlight the PM’s speeches, news, and announcements (ibid.). Similarly, the team is responsible for posting tweets on X that involve the PM’s speeches and statements, new photos, retweets, and live event coverages (www.gov.uk, 2024).

Corpus

The corpus of the present investigation involves Rishi Sunak’s discourse on climate change published in the form of Facebook status updates on his official Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/10downingstreet?locale=en_GB and tweets on his official X account at https://twitter.com/RishiSunak from 25 October 2022 (the day Sunak assumed office) to 25 October 2023 (i.e., one year). Based upon the literature (Kapranov, 2016), the timeframe of one year is considered to be sufficient for the corpus collection of the SNS-based data.

The reasoning for selecting contributions to the corpus involves the following considerations. First, Sunak’s Facebook status updates and tweets on X are searched for the presence of, at least, one of the following climate change-related themes: agriculture, energy, hazards, health, legislature, climate change mitigation, people’s everyday life, political and societal values, risk, security, transport, and weather events. Second, the selected updates and tweets are further searched for the presence of, at least, one of the following keywords: anthropogenic climate change, climate change/changes, climatic change, climate change adaptation, climate change mitigation, climate risk/risks, CO2 absorption, CO2 capture and storage, CO2 emission/emissions, CO2 emission reduction/reductions, extreme weather event/events, global warming, green energy, green energy efficiency, greenhouse gasses/GHG, green technology, net zero, offshore wind farm, sea level/levels, rise in sea level, wind energy, wind farm, the consequences of climate change, (the) health effects of climate change.

Once the relevant contributions to the corpus have been selected, they are downloaded from the respective SNSs and saved as a Word file, which is processed in the software program Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 (IBM, 2011) in order to compute the descriptive statistics of the corpus, inclusive of means (M) and standard deviations (SD) as demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1. The Descriptive Statistics of the Corpus

|

# |

Descriptive Statistics |

Value |

|

1 |

The total number (N) of entries both on Facebook and X |

68 |

|

2 |

The total N of words |

3 713 |

|

3 |

M words |

54.6 |

|

4 |

SD words |

42.4 |

|

5 |

Maximum words |

250 |

|

6 |

Minimum words |

8 |

Methodology

Methodologically, the study was anchored in the approach to framing in political and mass media discourse that was developed by Entman (1993, 2007, 2010a, 2010b), who regarded framing as “the process of culling a few elements of perceived reality and assembling a narrative that highlights the connections among them to promote a particular interpretation” (Entman, 2007, p. 4). In line with Entman’s definition, the methodology of frame analysis focussed on establishing the definition of the problem (in our case, the issue of climate change), its description, evaluative judgments associated with it (if any), and possible ways of its mitigation (Entman, 1993, p. 52). Furthermore, the present frame analysis factored in the following: (i) a culture-specific context of British political discourse, which was built upon a shared repertoire of social meanings (D’Angelo et al., 2019), (ii) engagement with written political discourse, in which key words and recurrent concepts played a crucial role in the identification of the frame (Connolly-Ahern & Broadway, 2008, p. 369), (iii) the juxtaposition of the data with the prior research that reported such generic frames as (a) Conflict (i.e., a conflict between individuals, groups, institutions or countries), (b) Economic Consequences (i.e., the consideration of economic gains and/or losses), (c) Human Interest (i.e., a human-centred perspective to the presentation of an issue or problem), (d) Human Impact (i.e., the description of people affected by an issue), (e) Morality (i.e., moral values and social expectations), and (f) Responsibility (i.e., the attribution of responsibility for causing or solving a problem or an issue) (Neuman et al.,1992; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000).

The methodological procedure of the corpus analysis involved the following steps: (i) multiple readings of each Facebook status update and tweet on X that pertained to the topic of climate change; (ii) the identification of recurring words, phrases and sentences that point out the issue of climate change; (iii) the identification of themes and categories in each Facebook status update and tweet on X, and their subsequent interpretation; (iv) the identification and quantification of the multimodal elements (if any) associated with the issue of climate change in each Facebook status update and tweet; (v) the verification of the manual identification procedure of key words and recurring phrases/sentences by means of the computer program AntConc version 4.0.11 (Anthony, 2022); (vi) the calculation of the frequency of the frames utilised in Rishi Sunak’s discourse on climate change in the corpus in SPSS (IBM, 2011); and, finally, (vii) the quantification of the multimedia used in conjunction with the framing in the corpus in SPSS (IBM, 2011).

It should be emphasised that the present frame analysis factored in multimedia elements that were involved in the Facebook updates and X tweets. In other words, the corpus elements, which contained a text and, for example, a video that accompanied the text, were analysed in their entirety, i.e. “text + video/videos”, “text + photo/photos”, and “text + video + photo.” The same principle was applied to other multimodal elements in the corpus, such as emojis, hyperlinks, and hashtags, if any (see Table 3 in the discussion of RQ 1). Another point in the methodological procedure, which, perhaps, should be clarified, involved the analysis of those few corpus elements that contained more than one frame. Only one Facebook status update involved two frames concurrently, which were analysed as two different, separate frames, whilst the rest of the corpus elements followed the pattern one frame per corpus element (i.e., one frame per Facebook update and tweet, respectively). Concluding the methodological part of the article, it should be pointed out that all the frames in the study were spelt with the capital letter in order to differentiate them from nonframe notions. To illustrate the point, Net Zero, which is spelt with the capital letters, denotes a frame in Sunak’s discourse on climate change, whereas net zero refers to a nonframe. Further, I present and discuss the frames in the corpus in the subsequent section of the article.

Results and General Discussion

The framing analysis that is outlined in the previous section of the article has yielded several frames that are used in Rishi Sunak’s discourse on the issue of climate change. These frames are as follows: British Jobs, Burden, Consent, Disruption, Energy Security, Green Technology, International Agreements, Net Zero, and Pragmatism. They are summarised in Table 2, which illustrates the types of frames in conjunction with the percentage of their occurrence to the total number of frames (N = 69).

Table 2. The Frames in Rishi Sunak’s Discourse on Climate Change on Facebook and X (Twitter)

|

# |

The Types of Frames |

Percentage in the Corpus |

|

1 |

Burden |

20.3 % |

|

2 |

Green Technology |

20.3 % |

|

3 |

Net Zero |

15.9 % |

|

4 |

Energy Security |

10.1 % |

|

5 |

Consent |

8.8 % |

|

6 |

Pragmatism |

8.7 % |

|

7 |

British Jobs |

5.8 % |

|

8 |

International Agreements |

5.8 % |

|

9 |

Disruption |

4.3 % |

It should be noted that the results outlined in Table 2 point to the presence of framing that involves the notion of net zero. As previously mentioned in the article section that sets the scene of the present investigation, net zero appears to constitute a frequently occurring aspect of British political discourse. Consequently, Sunak’s framing of climate change as Net Zero lends support to the literature (Booth, 2023; Gregory & Geels, 2024; Meckling & Allan, 2020; Paterson, 2021; Van Coppenolle et al., 2023), which demonstrates that the notion of net zero is incorporated into the current British political discourse on the issue of climate change. Another finding that follows from Table 2 is represented by the frame International Agreements, which reverberates with the literature (Johnston & Deeming, 2016; Porter et al., 2015; Webb & van der Horst, 2021; Youngs & Lazard, 2023), which posits that British political discourse on climate change is associated with legislative and statutory acts that aim at facilitating and adapting climate change-related laws and regulations. Additionally, the presence of the frames Green Technology and Pragmatism (see Table 2) buttresses the literature (Bowen & Rydge, 2011; Porter et al., 2015), which postulates that the British government considers climate change mitigation in conjunction with science- and technology-driven solutions (Johnston & Deeming, 2016).

Continuing the general discussion of the results, it is relevant to note that Rishi Sunak’s discourse on climate change does not involve frames that pertain to the consequences of climate change that are related to health, extreme weather events, and the rise of sea levels. Given that the aforementioned climate change-related areas of concern are not mentioned in the corpus, it is assumed that they are either epiphenomenal or irrelevant to Sunak’s government, or, perhaps both. Obviously, more research on Sunak’s climate change discourse in needed to support the absence of framing on the intersection of health-, extreme weather-, and sea rising-related events.

Now, let us discuss the results in detail from the vantage point of the RQs in the study. As indicated in the introduction, RQ 1 looks at the types of frames that are employed in Rishi Sunak’s discourse on climate change, whereas RQ 2 seeks to establish the most frequent of them.

Discussing RQ 1: The Types of Frames in Rishi Sunak’s Discourse on Climate Change

As evident from Table 2, Rishi Sunak’s framing of the issue of climate change on Facebook and X ranges from the risks associated with the negative consequences of climate change to burden as a fine example of political spin that involves Sunak’s over-accentuated attention to the needs of “a typical British family,” who should not bear the burden of reaching the targets of net zero. However, despite a seemingly disparate array of frames that are utilised in Sunak’s discourse on climate change on Facebook and X, we can distinguish two underlying patterns that bind all the heterogeneous frames in the corpus in a logical and explicable strategy, which, arguably, is pursued by Sunak and his digital communications team.

The first pattern consists in the ample use of multimodal elements in order to focus and/or emblematise Sunak’s stance on the issue of climate change. Judging from the data, his framing of climate change on both Facebook and X involves a substantial level of visual elements, such as photos, videos, hyperlinks, and emojis. To illustrate the point, let us, for instance, regard a tweet on X from 21 September 2023, in which Rishi Sunak writes that

(1) Today I was at @WrittleOfficial speaking with farming students about our new approach to reaching Net Zero by 2050 while easing the burden on working people. This is important for families in rural communities who face huge costs and are the backbone of their local economies. (Rishi Sunak, 2023)

Figure 1. An Illustration of the Multimodal Elements on Rishi Sunak’s X Account

In (1), Rishi Sunak’s framing of the issue of climate change as a financial burden on the working British people and families in rural areas, “who face huge costs and are the backbone of their local economies,” is accompanied by a visual element that is represented by the photo with Rishi Sunak in the foreground (see Figure 1). The aforementioned example emblematises a typical and, most importantly, recurrent strategy of his framing of climate change on both Facebook and X. In this regard, it should be mentioned that there are multiple instances of the utilisation of photos, videos, hyperlinks, and emojis in conjunction with Sunak’s framing of the issue of climate change, whilst hashtags are not used at all, as evident from Table 3 below.

Table 3. The Descriptive Statistics of Multimedia Elements in the Corpus

|

# |

Descriptive Statistics |

Value |

|

1 |

Emojis |

Total N 49 (M 3.1; SD 1.5) |

|

2 |

Hashtags |

- |

|

3 |

Hyperlinks |

Total N 10 (M 1.0; SD 0) |

|

4 |

Photos |

Total N 51 (M 1.1; SD 0.3) |

|

5 |

Videos |

Total N 19 (M 1.0; SD 0) |

To an extent, the findings summarised in Table 3 lend support to the literature, which points to the extensive use of multimodal elements, especially in the combination of text and photos, in the framing of climate change by British mass media (Batziou, 2022; Gillings & Dayrell, 2023; Guenther et al., 2022; Rathnayake & Suthers, 2023; Ruiu et al., 2023; Stoddart et al., 2023). It can be argued that the presence of numerous multimodal elements in Sunak’s framing of climate change is compatible with that of British media outlets. Furthermore, the multimedia presented in Table 3 are, quite often, reflective of Sunak’s individualised dimension of political communication (Farkas & Bene, 2021). It follows from the data that the multimedia, first of all, photos and videos that are used in Sunak’s discourse on climate change on Facebook and X, convey the image of Rishi Sunak both as a politician and a human being. The use of multimedia as a form of individualised political broadcasting (Farkas & Bene, 2021) is further illustrated by the finding that the majority of videos (69%) foreground Sunak’s personal presentations on the topic of climate change. In contrast, however, the foregrounding of Sunak on photos in conjunction with the topic of climate change is less common in the corpus (21%).

In addition to the multimedia that foreground Sunak visually, his personalised presence is further amplified linguistically by numerous self-mentions in the corpus. For instance, in the frame Consent, he utilises such self-mentions as the first person pronouns I and we, thus imparting the framing an additional personalised dimension via I, which is further coupled with we that facilitates the creation of a team-related aspect of framing, as illustrated by the following quote: “I care about reaching Net Zero by 2050 but on the current path, we risk losing the consent of the British people” (Sunak, 2023). Notably, self-mentions are used in all the types of frames that are summarised in Table 2.

Continuing our discussion of the types of frames in the corpus, we should notice that even though they differ in foci, they, nevertheless, manifest several underlying categories that permeate the seemingly diverse framing. For instance, British Jobs, Burden, Energy Security, Green Technology, Net Zero, and Pragmatism appear to be bound together by a distinct propensity to view the issue of climate change through the lenses of economy. In particular, when framing climate change as a Burden, Sunak foregrounds not so much an idealistic and morality- and ethics-driven category of burden, but he evokes quite explicitly the category of economic hardship and difficulties that working-class families have to bear due to the measures associated with net zero. Hence, the frame Burden in Sunak’s framing of climate change encapsulates an economy-related dimension. Whilst we will return to the discussion of the frame Burden further in the article, let us note that similarly to that frame, the frames British Jobs, Energy Security, Green Technology, Net Zero and Pragmatism are imbued with the spirit of market economy.

Likewise, the frames Disruption and International Agreements are bound together by a category associated with law, both domestic and international. As far the international law is concerned, Rishi Sunak indicates that “We will still meet our international commitments and hit Net Zero by 2050” (Sunak, 2023), whereas he refers to domestic laws when commenting on traffic obstruction as a form of civil resistance by Just Stop Oil, a British environmental activist group, e.g., “We’re giving police the support they need to quickly stop groups like Just Stop Oil from selfishly disrupting people’s daily lives” (Sunak, 2023). Given that both of these instances are embedded into the overarching theme of domestic legislature and international law-binding agreements, we may contend that they are unified by the category of law.

In a similar vein, we may distinguish a morality-related category represented by the frame Consent. In the frame, the attainment of zero CO2 emissions by 2050 is problematised as a moral concern that needs the permission of the British people to be pursued, as seen in (2):

(2) I care about reaching Net Zero by 2050 but on the current path, we risk losing the consent of British people. No one has yet had the courage to look people in the eye and explain what’s really involved. That’s wrong, and it changes with this new approach to meeting Net Zero. (Sunak, 2023).

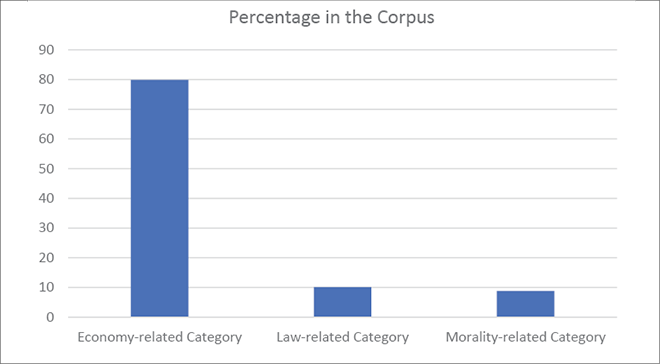

Hence, we may contend that the frames in the corpus are subsumed into several categories that are economy-, law-, and morality-related, as illustrated by Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. The Categories of Frames in the Corpus

It follows from Figure 2 that the most representative category of frames in the corpus is economy-related. The framing of climate change via an economic lens is, arguably, not at all surprising, given that Sunak worked as a financial analyst at Goldman Sachs and a number of hedge funds. In addition, he served as the Chief secretary to the Treasury (2019–2020) and the Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2020 to 2022. Consequently, we may argue that the economisation of climate change in Sunak’s discourse on Facebook and X is reflective of his mindset as a financier and, perhaps more importantly, as the current leader of the Conservative Party, which is renowned for its economy-related view on climate change (Garland et al., 2018).

Another finding that follows from the data analysis involves the correspondence of the economy-related frames (i.e., British Jobs, Burden, Energy Security, Green Technology, Net Zero, and Pragmatism) to several generic frames (Neuman et al., 1992; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000), in particular, Economic Consequences and Human Impact. Whilst the former generic frame is explicit in the frames British Jobs, Burden, Energy Security, Green Technology, Net Zero, and Pragmatism, the generic frame Human Impact (Neuman et al., 1992; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000) seems to be quite obvious in the frames British Jobs, Burden, and Pragmatism, in which Sunak describes how people’s lives are affected economically by the consequences of climate change mitigation.

Unlike the abovementioned frames, however, the frames Disruption and International Agreements, which pertain to the law-related category, correlate with the generic frame Responsibility (Neuman et al., 1992; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000), in which the attribution of responsibility for causing and/or solving a climate change-related problem rests with either international law in the frame International Agreements or domestic laws and regulations in Disruption. Additionally, the latter frame is congruous with the generic frame Conflict (Neuman et al., 1992; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000). In terms of the correspondence to the generic frames (Neuman et al., 1992; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000), the morality-related category that is represented by the frame Consent is compatible with the generic frame Morality, in which Sunak attributes responsibility to the British people for the decisions on the optimal ways of reaching net zero (Chen et al., 2023).

Another important observation that is drawn from the corpus is that Sunak does not seem to frame the issue of climate change within the context of Brexit. This finding is in contrast to the literature (Almiron et al., 2020; Gavin, 2018; Lockwood, 2018), which indicates that a substantial bulk of political discourse in the UK is embedded into the attitudinal and partisan lines associated with Brexit. Compared with the literature, Sunak’s framing of climate change is definitely shrouded in the post-Brexit rhetoric, at least as far as the period of time 2022–2023 is concerned.

Having discussed RQ 1, let us continue deliberating about the results from the standpoint of RQ 2, which explores the most frequent types of frames in Sunak’s discourse on climate change on Facebook and X.

Discussing RQ 2: The Most Frequent Types of Frames in Rishi Sunak’s Discourse on Climate Change

It should be reiterated that the frames Burden and Green Technology are the most frequent ones in the corpus (see Table 2). They are equally distributed and appear to pertain to the economy-related category. Judging from the data, the frames testify to the economisation of climate change by Sunak, whose framing of the issue encapsulates, first of all, economic forces (Almiron et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2023). Interestingly, the frames Burden and Green Technology are more frequent than the frame Net Zero, despite the fact that the catchphrase “net zero” is widely used in the current political discourse in the UK (Booth, 2023; Paterson, 2021; Van Coppenolle et al., 2023; Webb & van der Horst, 2021).

As previously mentioned, the frame Burden echoes two generic frames, namely Economic Consequences and Human Impact (Neuman et al., 1992; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000). Furthermore, the frame Burden reverberates with the literature, which points to the economisation of the issue of climate change by a variety of actors from the British political and business spectrum (Badullovich et al., 2020; Ferns & Amaeshi, 2021; Jaworska, 2018; Kristiansen et al., 2021; Nyberg et al., 2022). Whilst the economisation of climate change is foregrounded in the frame Burden, the present findings, however, seem to provide an angle that differs from the literature (Jaworska, 2018), which points to a substantial role that British fossil fuel corporations play in political discourse on climate change in the UK.

Whereas Sunak makes neither direct nor implicit mentions of the fossil fuel corporations in relation to Burden, he explicates it by means of referring to immense hardship the British working-class families are suffering from due to the measures associated with climate change mitigation, as seen in (3):

(3) “I am not going to be deterred from doing what I believe is right for the future of our children.” This morning Prime Minister @RishiSunak set out how our new approach to meeting Net Zero by 2050 will ease the burden on working people. (Sunak, 2023)

In other words, Sunak equates the 2050 target of reaching zero emissions with a financial burden and frames it as a political spin in his discourse on climate change in order to create a positive image of himself, his government, and, implicitly, of the Conservative Party as a caring political actor, who mitigates not only the negative consequences of climate change, but also negative repercussions of his climate change policies.

An equally frequent framing is represented by the frame Green Technology. To an extent, the framing of the issue of climate change via the lens of technology is present in the literature (Ferns & Amaeshi, 2021; Guenther et al., 2022; Kapranov, 2018; Ruiu et al., 2023; Stoddart et al., 2023), which, however, situates the notion of ecologically- and climate change-neutral technology within the context of media reporting and, less so, within the realm of politics. In the present corpus, the framing of climate change via Green Technology reflects, undoubtedly, a political stance of the current PM, who contextualises the use of ecologically-friendly technology to offset the negative consequences of climate change from the standpoint of the economy, as exemplified by excerpt (4):

(4) Our new approach will embrace with even greater enthusiasm, the incredible opportunities of green industry: We’re already home to the four largest offshore windfarms in the world. We’re now building nuclear power stations for the first time since the 1990s. And we’re investing billions in new energy projects - and speeding up the planning process to deliver them. This will create hundreds of thousands of good, well-paid jobs right across the country and ensure the UK remains the best place in the world to invest in the green industries of the future. (Sunak, 2023)

Notably, (4) represents a rather typical example of Sunak’s approach towards the economisation of ecologically-friendly technology, which he regards in conjunction with investment opportunities and the creation of new jobs. To conclude the discussion of RQ 2, we may argue that the economisation of technology, which is observed in the frame Green Technology, is invariably present in the frame Burden. Thus, we contend that these two frames are rather similar in essence, given that they are deeply entrenched in the economy-related aspects of climate change mitigation.

Conclusions

The article describes a study that examines the framing of the issue of climate change by Rishi Sunak, the current British PM, in the corpus of his Facebook updates and tweets on X. The results of the corpus analysis have revealed that Rishi Sunak’s discourse on climate change is structured by the frames British Jobs, Burden, Consent, Disruption, Energy Security, Green Technology, International Agreements, Net Zero, and Pragmatism. Whilst Sunak’s framing of climate change involves a seemingly heterogenous array of different foci and priorities, it is, nevertheless, reflective of his economy-oriented take on climate change. The most frequent frames in the corpus (i.e., Burden and Green Technology), which are also economy-oriented, only reinforce the importance of economy in Sunak’s approach towards climate change and the way it should be handled. Another important finding consists in Sunak’s ample use of multimedia in conjunction with the issue of climate change. Specifically, it has been uncovered that he incorporates a substantial number of multimodal elements in his Facebook status updates and tweets on X, such as, predominantly, videos and, less so, photos, which foreground the personal image of Sunak in the context of climate change discourse.

Summarising the major findings, it is concluded that Sunak’s framing of climate change is embedded in the economisation of the issue, which is framed by personalised multimodal elements (e.g., videos). These findings contribute to a better understanding of how the current British PM sees the issue of climate change and by what discursive means he frames his discourse on climate change on the SNSs. In other words, the present findings shed light on Sunak’s voice on climate change, an SNS-mediated voice that is largely political in nature, yet quite personal.

The aforementioned findings can contribute to the theoretical aspects of framing analysis by providing a set of data that could be used as a benchmark to be compared with climate change discourse by the non-EU actors, for example, Norway, which just like the UK is a constitutional monarchy governed by the prime minister. Given that Norway, identically to the post-Brexit UK, is not an EU member with a strong and continuous tradition of political pluralism and democracy, the framing of climate change discourse by the Norwegian prime minister (currently – Jonas Støre) may be adequately compared to that of Rishi Sunak. Another theoretical aspect in which the present data can be further used involves a possible comparison of Sunak’s framing of climate change with that by political actors from the British Commonwealth of Nations that share similar political traditions and the common language, which, in combination, make a good case for exploring whether or not Sunak’s framing of climate change via the lens of economisation is also taken on board by his Commonwealth counterparts.

Concluding, it appears logical to posit that the results of the study serve as an invitation to further research, especially in the direction of economisation and personification of the issue of climate change in British political discourse. Yet, one more possible avenue to be explored in future studies could involve the issue of Sunak’s authorship of posts concerning climate change on SNSs. Whilst it has been mentioned that a team of professionals handles Sunak’s Facebook and X accounts, it would be pertinent to ascertain to what extent the frames in Sunak’s climate change discourse are reflective of his own viewpoints and ideas and, correspondingly, to the extent those of his digital communications team. In this regard, future studies should take into consideration whether or not his digital communications team has a degree of autonomy in creating climate change-related content for the SNSs. Hopefully, the aforementioned research directions deserve future investigation.

Acknowledgments

The author is appreciative of the editor and anonymous reviewers.

Sources

https://www.facebook.com/10downingstreet?locale=en_GB

https://twitter.com/RishiSunak

References

Almiron, N., Boykoff, M., Narberhaus, M., & Heras, F. (2020). Dominant counter-frames in influential climate contrarian European think tanks. Climatic Change, 162(4), 2003–2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02820-4

Anthony, L. (2022). AntConc Version 4.0.11. Waseda University.

Araújo, B., & Prior, H. (2021). Framing political populism: The role of media in framing the election of Jair Bolsonaro. Journalism Practice, 15(2), 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1709881

Badullovich, N., Grant, W. J., & Colvin, R. M. (2020). Framing climate change for effective communication: a systematic map. Environmental Research Letters, 15(12), Article 123002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba4c7

Batziou, A. (2022). Climate change and the heatwave: Searching for the link in the British press. Journalism Practice, 16(4), 681–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2020.1808515

Bevan, L. D., Colley, T., & Workman, M. (2020). Climate change strategic narratives in the United Kingdom: Emergency, extinction, effectiveness. Energy Research & Social Science, 69, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101580

Bomberg, E. (2023). Global climate action: A political stocktake. Political Insight, 14(4), 31–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/20419058231218325

Booth, R. (2023). Pathways, targets and temporalities: Analysing English agriculture’s net zero futures. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 6(1), 617–637. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211064962

Bowen, A., & Rydge, J. (2011). Climate-change policy in the United Kingdom. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, (886). https://doi.org/10.1787/5kg6qdx6b5q6-en

Boykoff, M. T. (2008). The cultural politics of climate change discourse in UK tabloids. Political Geography, 27(5), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2008.05.002

Bulkeley, H., & Schroeder, H. (2008). Governing Climate Change Post-2012: The Role of Global Cities. Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research.

Carter, N., Ladrech, R., Little, C., & Tsagkroni, V. (2018). Political parties and climate policy: A new approach to measuring parties’ climate policy preferences. Party Politics, 24(6), 731–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068817697630

Carvalho, A. (2010). Media (ted) discourses and climate change: a focus on political subjectivity and (dis) engagement. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 1(2), 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.13

Carvalho, A., & Burgess, J. (2005). Cultural circuits of climate change in UK broadsheet newspapers, 1985–2003. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 25(6), 1457–1469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00692.x

Chen, K., Molder, A. L., Duan, Z., Boulianne, S., Eckart, C., Mallari, P., & Yang, D. (2023). How climate movement actors and news media frame climate change and strike: evidence from analyzing twitter and news media discourse from 2018 to 2021. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 28(2), 384–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612221106405

Connolly-Ahern, C., & Broadway, S. C. (2008). “To booze or not to booze?” Newspaper coverage of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Science Communication, 29(3), 362–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547007313031

D’Angelo, P., Lule, J., Neuman, W. R., Rodriguez, L., Dimitrova, D. V., & Carragee, K. M. (2019). Beyond framing: A forum for framing researchers. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 96(1), 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018825004

De Boer, J., Wardekker, J. A., & Van der Sluijs, J. P. (2010). Frame-based guide to situated decision-making on climate change. Global Environmental Change, 20(3), 502–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.03.003

de Moor, J. (2022). Postapocalyptic narratives in climate activism: their place and impact in five European cities. Environmental Politics, 31(6), 927–948. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1959123

Elías-Zambrano, R., Expósito-Barea, M., Jiménez-Marín, G., & García-Medina, I. (2019). Microtargeting and electoral segmentation in advertising and political communication through social networks: Case study. The Journal of Social Sciences Research, 5(6), 1052–1059. https://doi.org/10.32861/jssr.56.1052.1059

Entman, R. M. (2010a). Framing media power. In P. D’Angelo & J. Kuypers (Eds.), Doing News Framing Analysis: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives (pp. 331–355). Routledge.

Entman, R. M. (2010b). Media framing biases and political power: Explaining slant in news of Campaign 2008. Journalism, 11(4), 389–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884910367587

Entman, R. M. (2007). Framing bias: Media in the distribution of power. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00336.x

Entman, R. M. (2004). Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion, and U.S. Foreign Policy. University of Chicago Press.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58.

Entman, R. M., Matthes, J., & Pellicano, L. (2009). Nature, sources, and effects of news framing. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), The Handbook of Journalism Studies (pp. 175–190). Routledge.

Falkenberg, M., Galeazzi, A., Torricelli, M., Di Marco, N., Larosa, F., Sas, M., Mekacher, A., Pearce, W., Zollo, F., Quattrociocchi, W., & Baronchelli, A. (2022). Growing polarization around climate change on social media. Nature Climate Change, 12(12), 1114–1121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01527-x

Farkas, X., & Bene, M. (2021). Images, politicians, and social media: Patterns and effects of politicians’ image-based political communication strategies on social media. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(1), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220959553

Ferns, G., & Amaeshi, K. (2021). Fueling climate (in) action: How organizations engage in hegemonization to avoid transformational action on climate change. Organization Studies, 42(7), 1005–1029. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840619855744

Garland, R., Tambini, D., & Couldry, N. (2018). Has government been mediatized? A UK perspective. Media, Culture & Society, 40(4), 496–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717713261

Gavin, N. T. (2018). Media definitely do matter: Brexit, immigration, climate change and beyond. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20(4), 827–845. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148118799260

Gillings, M., & Dayrell, C. (2023). Climate change in the UK press: examining discourse fluctuation over time. Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amad007

Gregory, J., & Geels, F. W. (2024). Unfolding low-carbon reorientation in a declining industry: A contextual analysis of changing company strategies in UK oil refining (1990–2023). Energy Research & Social Science, 107, Article 103345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103345

Guenther, L., Brüggemann, M., & Elkobros, S. (2022). From global doom to sustainable solutions: International news magazines’ multimodal framing of our future with climate change. Journalism Studies, 23(1), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.2007162

Harcourt, R. S. (2020). Narrating the UK’s adaptation to a changing climate: Identifying the most prominent adaptation narratives from the public discourse and understanding how engaging they are for UK residents [Doctoral dissertation, University of Leeds].

Hess, D. J., & Renner, M. (2019). Conservative political parties and energy transitions in Europe: Opposition to climate mitigation policies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 104, 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.01.019

IBM. (2011). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 20.0). IBM.

Jaworska, S. (2018). Change but no climate change: Discourses of climate change in corporate social responsibility reporting in the oil industry. International Journal of Business Communication, 55(2), 194–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488417753951

Johnston, R., & Deeming, C. (2016). British political values, attitudes to climate change, and travel behaviour. Policy & Politics, 44(2), 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557315X14271297530262

Kapranov, O. (2018). Conceptual metaphors associated with climate change. In R. Augustyn & A. Mierzwinska-Hajnos (Eds.), New Insights into the Language and Cognition Interface (pp. 51–66). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Kapranov, O. (2016). The framing of Serbia’s EU accession by the British Foreign Office on Twitter. Tekst i Dyskurs–Text und Diskurs, 9(9), 67–80.

Kristiansen, S., Painter, J., & Shea, M. (2021). Animal agriculture and climate change in the US and UK elite media: volume, responsibilities, causes and solutions. Environmental communication, 15(2), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2020.1805344

Lockwood, M. (2018). Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: exploring the linkages. Environmental Politics, 27(4), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1458411

Meckling, J., & Allan, B. B. (2020). The evolution of ideas in global climate policy. Nature Climate Change, 10(5), 434–438. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0739-7

Neuman, W. R., Just, M. R., & Crigler, A. N. (1992). Common Knowledge: News and the Construction of Political Meaning. University of Chicago Press.

Nightingale, A. J. (2017). Power and politics in climate change adaptation efforts: Struggles over authority and recognition in the context of political instability. Geoforum, 84, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.05.011

Nyberg, D., Ferns, G., Vachhani, S., & Wright, C. (2022). Climate change, business, and society: Building relevance in time and space. Business & Society, 61(5), 1322–1352. https://doi.org/10.1177/00076503221077452

Ophir, Y., Forde, D. K., Neurohr, M., Walter, D., & Massignan, V. (2023). News media framing of social protests around racial tensions during the Donald Trump presidency. Journalism, 24(3), 475–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849211036622

Paterson, M. (2021). ‘The end of the fossil fuel age’? Discourse politics and climate change political economy. New Political Economy, 26(6), 923–936. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2020.1810218

Pielke Jr, R., & Ritchie, J. (2021). Distorting the view of our climate future: The misuse and abuse of climate pathways and scenarios. Energy Research & Social Science, 72, Article 101890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101890

Porter, J. J., Demeritt, D., & Dessai, S. (2015). The right stuff? Informing adaptation to climate change in British local government. Global Environmental Change, 35, 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.10.004

Rathnayake, C., & Suthers, D. (2023). Towards a ‘pluralist’approach for examining structures of interwoven multimodal discourse on social media. New media & Society, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231189800

Rousseau, A. (2023). Reciprocal relationships between adolescents’ incidental exposure to climate-related social media content and online climate change engagement. Communication Research, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502231164675

Ruiu, M. L., Ruiu, G., & Ragnedda, M. (2023). Lack of ‘common sense’in the climate change debate: Media behaviour and climate change awareness in the UK. International Sociology, 38(1), 46–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/02685809221138356

Scheufele, D. A. (2017). Agenda-setting, priming, and framing revisited: Another look at cognitive effects of political communication. In R. Wei (Ed.), Refining Milestone Mass Communications Theories for the 21st Century (pp. 71–90). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315679402

Semetko, H. A., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2000). Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. Journal of Communication, 50(2), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02843.x

Son, Y. A., & Jun, J. W. (2024). Effects of risk perception, SNS uses, personal characteristics on climate change participation behaviors of millennials in South Korea. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), Article 2318793. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2024.2318793

Stoddart, M. C., Ramos, H., Foster, K., & Ylä-Anttila, T. (2023). Competing crises? Media coverage and framing of climate change during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environmental Communication, 17(3), 276–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2021.1969978

Tankard Jr, J. W. (2001). The empirical approach to the study of media framing. In S. D. Reese, O. H. Gandy, Jr., & A. E. Grant (Eds.), Framing Public Life (pp. 111–121). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410605689

Taylor, A. L., Dessai, S., & de Bruin, W. B. (2014). Public perception of climate risk and adaptation in the UK: A review of the literature. Climate Risk Management, 4, 1–16.

Van Coppenolle, H., Blondeel, M., & Van de Graaf, T. (2023). Reframing the climate debate: The origins and diffusion of net zero pledges. Global Policy, 14(1), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13161

Wagner, P. (2023). The triple problem displacement: Climate change and the politics of the Great Acceleration. European Journal of Social Theory, 26(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310221136083

Webb, J., & van der Horst, D. (2021). Understanding policy divergence after United Kingdom devolution: Strategic action fields in Scottish energy efficiency policy. Energy Research & Social Science, 78, Article 102121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102121

Whitmarsh, L., & Capstick, S. (2018). Perceptions of climate change. In S. Clayton & C. Manning (Eds.), Psychology and Climate Change (pp. 13–33). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2016-0-04326-7

gov.uk. (2024). Social media use. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/prime-ministers-office-10-downing-street/about/social-media-use

Youngs, R., & Lazard, O. (2023). Climate, ecological and energy security challenges facing the EU: new and old dynamics. In T. Rayner, K. Szulecki, A. J. Jordan, & S. Oberthür (Eds.),

Handbook on European Union Climate Change Policy and Politics (pp. 158–172). Edward Elgar Publishing.