Information & Media eISSN 2783-6207

2023, vol. 98, pp. 23–52 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2023.98.61

Social Media Strategies for Gender Artivism: A Generation of Feminist Spanish Women Illustrator Influencers

Isabel Palomo-Domínguez (Correspondence author)

Mykolas Romeris University, Lithuania

isabel.palomo@mruni.eu

Gloria Jiménez-Marín

University of Seville, Spain

Nuria Sánchez-Gey Valenzuela

University of Pablo de Olavide, San Isidoro Center, Spain

Abstract. Nowadays, social networks play a central role in communication media. In this scenario, analysing the gender awareness fostered by the influencers is crucial.

The research explores the female representation portrayed by eight Spanish influencers who address the gender approach from graphic communication. All of them are women illustrators, cover topics related to gender, and use similar communication strategies.

The methodology includes three complementary techniques: first, desktop study to compare the illustrators’ profiles; second, content analysis to delve into the topics addressed and their artivism; third, a Delphi method to assess their contribution to promoting gender egalitarian values, in which experts specialising in communication, philosophy, sociology, psychology, and politics participate.

The results show that feminism is a prominent topic in their publications, stimulating a feeling of sisterhood among women, their core target. From a generational perspective, the influence of their message is more significant on millennials and centennials. Conclusions confirm that social media characteristics, artivism, content hybridisation and transmediality enhance their feministic discourse. Future lines of research may focus on identifying other channels and communication strategies more influential for broad target groups, especially men and generations older than millennials, since these external audiences seem crucial to spread gender awareness.

Keywords: Feminism; Social Media; Artivism; Transmediality; Illustrators.

Socialinių medijų strategijos lyčių lygybės artivizme. Ispanių feminisčių iliustratorių nuomonės formuotojų karta

Santrauka. Mūsų laikais socialiniai tinklai yra svarbi komunikacijos priemonių dalis, todėl yra svarbu nagrinėti, kaip nuomonės formuotojai skatina lyčių lygybę.

Tyrime analizuojama, kaip aštuonios ispanės nuomonės formuotojos, kalbančios apie lyties aspektą grafinėmis komunikacijos priemonėmis, atstovauja moterims. Jos visos yra iliustratorės, kalbančios su lytimi susijusiomis temomis ir naudojančios panašias komunikacijos strategijas.

Taikoma metodika apima tris papildomas technikas: pirma, teorinė analizė, skirta iliustratorių profiliams palyginti; antra, turinio analizė, skirta išnagrinėti aptariamas temas ir jų artivizmą; trečia, Delfi metodas, skirtas įvertinti jų indėlį, skatinant lyčių lygybę; taikant šį metodą dalyvauja komunikacijos, filosofijos, sociologijos, psichologijos ir politikos sričių ekspertai.

Rezultatai rodo, kad jų publikacijose ryški feminizmo tema, skatinanti seserystę tarp moterų, kurios yra jų tikslinė auditorija. Vertinant kartų aspektu, jų skleidžiama žinutė yra svarbesnė Z ir Y kartų atstovėms. Išvados patvirtina, kad socialinės medijos bruožai, artivizmas, turinio hibridizacija ir transmedialumas stiprina jų feministinį diskursą. Būsimos tyrimų kryptis galėtų nustatyti kitus kanalus ir komunikacijos strategijas, turinčias daugiau įtakos plačioms tikslinėms grupėms, ypač vyrams ir ankstesnėms kartoms nei Y karta, nes šios išorės auditorijos yra svarbios skatinant lyčių lygybę.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: feminizmas; socialinės medijos; artivizmas; transmedialumas; iliustratorės.

Received: 2022-06-10. Accepted: 2023-06-26.

Copyright © 2023 Isabel Palomo-Domínguez, Gloria Jiménez-Marín, Nuria Sánchez-Gey Valenzuela. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Since Linda Nochlin (1971) published her famous essay “Why have there been no great women artists?” the question remains open and debated by numerous authors. This sort of oblivion and invisibility (Gil Salinas & Lomba, 2021) has accompanied women for centuries, not only in arts but also in numerous science and social fields.

Some decades later, gender equality is still a pending goal for our civilisation, describing a disproportionate distribution of opportunities patent in many spheres, among them in the workplace and the public life (Bruckmüller & Braun, 2020; Dashper, 2019; Hideg & Krstic, 2021).

An example of this is the unfair incongruence that takes place in the Spanish communication industry: on the one hand, women are the majority studying communication at university; on the other, they are a minority in positions of power within this professional sector, remaining stagnant in lower and middle charges (Jiménez-Marín et al., 2022).

In this scenario, eight Spanish illustrators call to attention: María Hesse, María Herreros, Moderna de Pueblo,1 María Gómez, Flavita Banana,2 Lola Vendetta,3 Precariada4 and Nazareth Dos Santos. Two of them, Flavita Banana and Lola Vendetta are already among the Spanish influencers more committed to gender awareness, according to the study conducted by Martín-García & Martínez-Solana (2019). The present research aims to determine if the eight illustrators can be considered a generation. In other words, if they all meet the geographical, temporal, thematic and medium criteria typically considered when analysing generations of communication creators (Palau-Sampio & Cuartero-Naranjo, 2018).

An introductory approach leads to thinking they constitute a new generation of illustrators. They all are from Spain, and although the Internet offers the opportunity to spread the message worldwide, they mainly target a Spanish audience. Regarding their generational profile, the eight illustrators were born in a period of 11 years, from 1982 to 1993, which describes them as millennials belonging to Gen Y (Thomas et al., 2020). Besides being influencers, they are coetaneous graphic authors who share the current temporal and cultural moment.

Moreover, the channels, formats, contents, tone and style they use in their communication present significant similarities. They have reached a relevant media position, particularly on Instagram, where most of them are ‘macro-influencers’ since they have over 170,000 followers, according to the influencer ranking by Ho (2020). From this starting point, the article delves into a more profound analysis of their media and message strategy. Besides, it poses a reflexive evaluation of their discourse’s relevance and impact on the audience, considering not only the core target (women from Gen Y and Gen Z) but the broad one (men and people from older generations).

Literature Review

The Generation Concept

The generation idea goes beyond the merely sociodemographic context and has been analysed from many disciplines (Burga-Díaz, 2021). Among them from philosophy, in which Ortega y Gasset‘s Theory of Generations (1933) stands out. According to the Spanish philosopher, a generation is not a handful of distinguished men nor simply a mass. It is a whole new social body with a determined life trajectory. Ortega y Gasset (1933) argues that the changes of time are due to variations in vital sensitivity, which translate into the change of generations; that is, in the displacement of an old generation by a new one.

A generation of authors brings together a group of creators who, in addition to sharing the same moment in time, have a series of common characteristics. These features encompass the same geographical context, addressing similar themes, presenting similar styles, and a common communicative dissemination strategy using the same discourses, channels and formats (Palau-Sampio & Cuartero-Naranjo, 2018; Torroella-Bribiesca, 2021).

In 1930, the German literary scholar Julius Petersen published his work Literary Generations, in which he established the criteria determining whether a group of authors constituted a generation. According to Petersen (1930), literary generations bring together a group of authors who share the following characteristics:

• Coincidence of birth: having been born in the time frame of the next few years.

• Homogeneity of education: refers to the authors‘ similar educational opportunities and achievements without large gaps or inequalities.

• Interpersonal relationships: authors of the same generation know each other, share acts, and admire each other.

• Event or generational experience: elements of a historical and social nature determine how the authors of the same generation face the world.

• Leadership: in each generation, the authors have a reference figure, a prominent author who unites and promotes the group.

• Generational language: the authors share topics and style. These common hallmarks come to constitute the language of the generation.

Almost a hundred years later, Petersen is still a valid and remarkable source for researchers currently reflecting on the concept of generation (Soufas, 2022; Winter, 2023).

The generation concept is also relevant to describe the target audience in media and persuasive communication. Knowing specific common generational characteristics makes it possible to address different segments of the public adapted to the characteristics of the message and the chosen medium to achieve more effective and impactful communication. Generation Y (also called millennials, born after 1980) and Generation X (centennials, born after 1995) have in common the importance they attach to social networks for information and entertainment. They are also characterised by being incredibly receptive to transmedia strategies and messages of a hybrid nature, which combine different types of discourse (Palomo-Domínguez & Zemlickienė, 2022; Thomas et al., 2021).

Artivism and Women

Arts seem to show a particular commitment when reporting all types of injustices— gender inequality is among them. Sánchez-Rubio (2017) argues that, in the field of graphic design and plastics arts, many women creators “have found in feminism a way to reconcile ideology and profession” (p.77).

Some of them have made their careers living examples of feminism. In this sense, Guida (2020) highlights the “almost heroic” role (p. 607) of the women graphic designers who, after the Second World War, exercised their profession with total autonomy, developing their business projects in a predominantly male world. Cases such as those of Emma Bonazzi, Tigiù (1881–1959) or Anita Klinz (1923-2013) illustrate a challenging breakdown of stereotypes in a traditional society where terms like ‘glass ceiling’ did not exist in the language yet but did in daily life.

Other graphic creators channelled their defence of feminism through ‘artivism’. Artivism uses artistic expressions, aesthetics and symbolism to stimulate public awareness and knowledge of specific historical facts and social attitudes, calling the audience to get involved and (re)act (Raposo, 2015). In short words, “Artivism enacts activism through art” (Bräuchler, 2022, p. 41).

Among many other references, examples of artivism focused on a gender perspective are the Feminist Art Movement in the United States and the Guerrilla Girls collective. The first began in 1970 and brought together creators such as Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, Suzanne Lacy, Judith Bernstein, Rachel Rosenthal and Sheila Levrant de Bretteville (Fernández-Rincón, 2019). Fifteen years later, the Guerrilla Girls appeared in New York’s art scene to denounce inequality based on race and gender, mainly through the graphic language of its posters, of an advertising nature, and the use of performance to call for action in space (Leng, 2020).

In the last two decades, examples of artivist movements driven by social networks have multiplied. They address different themes and give visibility to protests launched from different countries and communities, often by minority groups that, prior to social networks, were condemned to invisibility. Artivist phenomena like the Pussy Riot, the feminist protest and performance art group (Silverman, 2020); the Chouftouhonna Feminist International Art Festival in Tunis, fostering the LGBTQ+ claims (Borrillo, 2020); the feminist artivism in the Chilean Social Revolt (De Fina-González, 2021); or Wonder Feminism comics, an Italian artivist project against gender violence are only some case studies among many others (Mandolini, 2022).

Social networks present significant advantages for artivism: younger audiences are quickly gained by these movements; the dissemination of the message is more agile through hashtags; it is possible to reach an international audience; collectives that previously feared demonstrating or could not find an audience now feel empowered; global crises, as Coronavirus pandemic, cannot spot the artivist work when it takes place in the digital sphere. Such are the benefits that the online world offers to activism that many of the movements have migrated their field of work, leaving the theatre scene and the town square to the social network scenario (Bernárdez-Rodal et al., 2019; Shymko et al., 2022).

Furthermore, social networks encourage collaboration between artivists from different territories and synergy between groups that pursue different but complementary interests. Authors such as Mandoni (2022) promote this type of collaboration between diverse artivist groups based on the idea that it propers a broader and more inclusive social transformation: “a deeper involvement of artivists with transnational intersectional feminist movements generally corresponds to a more inclusive, effective and participative artivistic product” (p. 1).

Feminism and Social Media

The irruption of the Internet in the early 90s amplified the claiming power of multiple causes, empowered by an interactive platform of democratic access (Baigorri & Cilleruelo, 2003). In this context, and especially with the expansion of social networks, feminism ceases to be just a social or political movement (Sau, 2001). It became a claim, a conversation topic, and a way of life that defends itself (Aránguez-Sánchez, 2019; Ramírez-Morales, 2019).

Authors such as Barranchina (2019) and Sanchez-Gey (2018) argue that social networks are an instrument of collaborative learning, significantly helpful to disseminating the feminist movement and essential to expanding information and educating from a gender perspective. Also, to denounce machismo, empower the community and fight against the patriarchal hegemony.

Some activist topics reflect Internet users’ commitment to fostering gender awareness on social networks: the defence of women’s reproductive freedom, their labour rights, and a severe denouncement against sexual violence and femicide. Most of them are usually synthesised in popular hashtags like #MeToo (Esquivel-Domínguez, 2019).5 In this context, some women graphic artists, such as the studied Spanish illustrators, portray a daily life that is still unequal for men and women (Palau-Sampio & Cuartero-Naranjo, 2018; Suárez-Carballo et al., 2021).

This feminist revolution has to do with the structural essence of digital media. Internet and social networks have transformed the media industry rules. This is not only due to the vast array of new channels and formats born in the online scenario but also because digital media have removed some privileges that have traditionally existed since the very beginning of the media age. Nowadays, receivers are not only receivers. The Lasswell model (Lasswell, 1948), in which an active sender drove a message to a passive receiver, has been reinvented. Now, receivers are prosumers, active recipients that produce information about the products and ideas they consume (Bartosik-Purgat & Bednarz, 2021; González-Oñate et al., 2020; Jiménez-Marín et al., 2021). Furthermore, they are committed to expanding activist movements that gain their engagement.

Transmediality, Hybridisation and Personal Branding

The concept of transmediality, attributed to Henry Jenkins (2010), has its direct precedent in the term transmedia intertextuality, coined by Kinder (1991) to refer to the relationships between television and cinema, video games and toys. Transmediality is involved in the complex process of launching a message through different channels and formats. For instance, a film, a piece of news, a website, a videogame, a publication on social media, or an art exhibition. The receiver, described above as an active receiver, integrates all the information from different channels and formats and creates a more comprehensive message.

Digital media usually unfolds a transmedia language. At this point, the interaction and net structure of new media fosters an idyllic scenario for transmediality:

The connectedness of today’s media industries, be it in terms of their digital platforms or across sectors such as digital and mobile communications, advertising, and marketing, and so on, is itself a defining underpinning characteristic of transmediality (Freeman, 2021, p. 404).

Often hand in hand with transmediality, the hybridisation phenomenon appears to meet the needs and interests of consumers belonging to the entertainment society (Álvarez, 2020; Arrivé, 2021; Del Pino-Romero & Olivares-Delgado, 2007). In this society, culture, communication, and entertainment interweave their discourses, composing a whole that acquires a prominent role in the lives of individuals. It takes various forms, whether that of a “best-seller, video game, concert, movie, popular dance, [...] tourist experience or sports show” (Martínez, 2011, p. 17).

Social media content is predominantly hybrid. An Instagram caption can combine elements of the influencer’s private life and promotion of his/her personal brand, promotion of another commercial brand, environmental awareness or a news story of international relevance. All the elements appear integrated into this mixture, so isolating and differentiating them is very complicated. This degree of seamless integration can confuse the public, who are unaware of the intention behind it (Palomo-Domínguez & Infante, 2022; Ramos-Gutiérrez & Fernández-Blanco, 2021). In any case, it is presented as a mode of communication especially appreciated by generations Y and Z, who better accept this type of hybrid message.

These communication strategies, transmediality, hybridisation and personal branding, are great allies in disseminating feminist ideas through artivist movements in the social media scenario. They could constitute the generational language that Petersen (1930) pointed out as one requirement of any generation of authors in the illustrators analysed in this research.

Methods

The research problem is the artivist social communication carried out by a group of Spanish illustrators on the Instagram social network.

The research pursuits three objectives:

• RO 1. Describe the communication strategy developed by these eight illustrators.

• RO 2. Determine if they all can be considered a generation. In other words, if the characteristics they share are solid enough to identify them as a consolidated and genuine group.

• RO 3. Assess the relevance of their discourse and influence. More specifically, their ability to spread a feminist message and stimulate awareness of the need for fair gender expression.

Regarding the research methodology, a triangulation design combines three techniques, blending quantitative and qualitative approaches (Gómez-Diago, 2010; Renz et al., 2018).

• Desktop research to draw the illustrator’s profile.

• Content analysis of illustrator’s social media publications.

• Delphi Method to collect the experts’ opinions on the topic.

Desktop Research

The desktop research started from online inquiries made on one browser, Google Chrome, with five keywords in the Spanish language: influencer, ilustradora,6 feminista,7 española,8 Instagram. The browser results showed several illustrators; the eight selected appeared within the top positions.

The same five keywords served to choose 20 magazine articles on this topic, all published from 2020 to May 2022. In most cases, the headlines mentioned a list of illustrators who defended feminism in the networks, becoming relevant influencers—for example, “Mujeres ilustradoras (muy top) de nuestro país”9 (Megías, 2022); or “8-M: Ocho cuentas feministas de Instagram que deberías seguir”10 (Rodríguez, 2021). These articles are examples of publicity or earned media (Visser, 2021) since illustrators benefited from promotional support for their brands without paying the media to publish the articles.

Some belonged to general audience media, others addressed the female audience, and others specialised in specific topics such as creative communication or trends in social networks (see Table 1). The diversity of the sources was considered a positive point for the research: firstly, because it was a set of sources capable of reaching a diverse audience; secondly, because this diversity was consistent with the transmedia strategy concept addressed in the research. The articles cited various illustrators; among them, the eight selected were the ones who presented more similarities in their descriptions. This remarkable similarity was considered the selection criterion for choosing the illustrators of this research.

Table 1. Desktop Research Sources: Illustrators’ Earned Media

|

Media Orientation |

Newspaper/Magazine/Website/ |

Author, Year |

|

General Audience |

Diario de Sevilla Pontevedra Viva El Español El Diario Huffington Post El Español |

Bellido, 2022 Espiño & Patxot, 2021 Fernández, 2022 Gallego, 2021 Prats, 2022 Serrano, 2022 |

|

Female Audience |

Elle Moda Cosmopolitan Feminismo Andaluz En Feminino In Style Telva |

Alonso, 2021 Cañedo, 2022 Gallego, 2020 Nieto, 2020 Rustarazo, 2020 Suárez, 2020 |

|

Specific Topics: Creative Communication and Social Media Trends |

Trendencias Metal Magazine El Salto Diario Communitools Alto y Claro Jot Down La Neta Flooxer Now |

De la Torre, 2021 Fabregat, 2021 Gaibar, 2022 Goldszmidt, 2021 Megías, 2022 Olmeda, 2021 Reyes, 2020 Rodríguez, 2020 |

Subsequently, the desktop research focused on the eight illustrators’ owned media, specifically on their official websites (see Table 2). These platforms are considered owned media since they belong to the illustrator and are controlled by them (Visser, 2021). Each website was analysed to identify similarities and differences between the illustrators, their works and communication strategies.

Table 2. Desktop Research Sources: Illustrators’ Owned Media

|

Illustrators |

Websites |

|

María Hesse |

|

|

María Herreros |

|

|

Moderna de Pueblo |

|

|

María Gómez |

|

|

Flavita Banana |

|

|

Lola Vendeta |

|

|

Precariada |

|

|

Nazareth Dos Santos |

Content Analysis

Content Analysis is a highly consolidated methodology within the field of communication (Herring, 2004). For this research, the study corpus includes all the Instagram captions posted by the eight illustrators during the first trimester of 2022, reaching 240 analysis units (N=240). The number of captions by each illustrator varies, but all the illustrators are sufficiently represented in the sample (see Table 3).

Table 3. Content Analysis: Study Corpus Structure

|

Illustrators |

Number of Captions per Illustrator |

Percentage in the Sample |

|

María Hesse |

37 |

9,6% |

|

María Herreros |

36 |

9,2% |

|

Moderna de Pueblo |

34 |

14,2% |

|

María Gómez |

35 |

9,6% |

|

Flavita Banana |

23 |

14,6% |

|

Lola Vendeta |

22 |

15,4% |

|

Precariada |

23 |

15,0% |

|

Nazareth Dos Santos |

30 |

12,5% |

Once the study corpus was delimited, the units of analysis were observed to identify features in their aesthetic form and content that would serve to define categories.

The categories were grouped into three sections. A general one, with open field categories to describe the reach of each illustrator on the Instagram social network during the study period. A second section with categories that serve to illustrate the aesthetic form and the narrative structure of their publications. A third section, the most important for research, identifies the topics covered in the posts, grouping them into subcategories (see Table 4).

Table 4. Content Analysis: Categories and Subcategories

|

Part A. General |

|

|

A#1: Illustrator’s Name |

Open field |

|

A#2: Number of Followers on Instagram |

Open field |

|

A#3: Number of Posts during the period |

Open field |

|

A#4: Number of Posts on Feminism’s Topics |

Open field |

|

Part B. Aesthetic Form and Narrative Structure |

|

|

B#1: Content Nature |

B#1#1: Illustration |

|

B#1#2: Picture |

|

|

B#1#3: Video |

|

|

B#2: Colour Use |

B#2#1: Full Colour |

|

B#2#2: Black & White |

|

|

B#3: Copy Content |

B#3#1: Textual Content in the Image |

|

B#3#1: No Textual content in the Image |

|

|

B#4: Characters |

B#4#1: Only Female Characters |

|

B#4#2: Only Male Characters |

|

|

B#4#3: Female and Male Characters |

|

|

B#5: Female Characters’ Representation |

B#5#1: Idealised Normative Bodies |

|

B#5#2: Diversity & Inclusion |

|

|

B#6: Tone |

B#6#1: Ironic Humour |

|

B#6#2: Severity & Anger |

|

|

B#6#3: Kindness & Empathy |

|

|

Part C. Topics |

|

|

C#1: Feminism |

C#1#1: Self-esteem |

|

C#1#2: Diversity |

|

|

C#1#3: Sexuality |

|

|

C#1#4: Gynaecological health |

|

|

C#1#5: Sisterhood |

|

|

C#1#6: Violence |

|

|

C#1#7: Machismo |

|

|

C#1#8: Glass ceiling |

|

|

C#1#9: Genre Inequality |

|

|

C#1#10: Patriarchy |

|

|

C#2: Today’s Issues |

C#2#1: Job insecurity |

|

C#2#2: Racism |

|

|

C#2#3: Environment & Sustainability |

|

|

C#2#4: Healthy nutrition |

|

|

C#2#5: Mental & Emotional health |

|

Delphi Method

Delphi Method is suitable for exploring unknown scenarios and addressing complex cases with opposing perspectives (Landeta, 2006; Reguant-Álvarez & Torrado-Fonseca, 2016). A total of eight experts in communication, sociology, philosophy, psychology and politics share their points of view until reaching a group consensus on the relevance and impact of illustrators’ feminist discourse. The criteria for choosing the experts were three:

1. Having more than ten years of experience in the social sciences, either as an academic or professional researcher.

2. Being specialised in issues related to feminism.

3. Only women experts participate in the survey.

The research was conducted in two iterations, which took place in May 2022. The first round launched close-ended and open-ended questions to the experts, the latter to capture their opinion in an exploratory way. The second round only included closed-ended questions to reach statistical validation (Campos-Climent et al., 2014; Landeta, 1999). The criteria for whether group consensus exists is that the interquartile range is equal to or less than 1 (k ≤ 1) for five-point Likert scale questions. For multiple-choice questions, the consensus is achieved from 80% relative frequency (Mateos-Ronco & Server, 2011).

Results

Similarities that Build a Generation

As mentioned above, the eight illustrators fulfil the similarities regarding geographical, temporal, thematic and medium criteria.

Considering the communication strategy, they have in common three relevant characteristics:

• They use transmedia language.

• They have built a powerful personal brand.

• They encourage their audience to have a sort of activist engagement. Since this activity is propelled from the artistic perspective, it could be considered artivism.

About their transmedia strategy, it should be noted that, in addition to their activity on Instagram and other social networks:

• The studied illustrators are authors of printed and editorial works.

• They have e-commerce websites to sell their graphic works and merchandising pieces (such as t-shirts, tote bags, or cups).

• They often take part in cultural events.

• Furthermore, they frequently are interviewed on radio or television cultural programmes, so they also have offline exposure.

Their captions in Instagram include elements from three different spheres of communication, as a revealing example of how hybridisation works:

• Professional elements. Pictures of finished or ongoing works; videos while drawing; projects in which they participate as illustrators; interviews and media events.

• Personal elements. Moments of their daily life, experiences that have marked them positive or negative and take stock from a feminist perspective, questions and direct messages to the followers.

• Commercial elements. The illustrators recommend some brands of different types of products. The commercial content appears less frequently than the professional and personal—except in the case of Moderna de Pueblo, the illustrator with a more prominent advertising activity among the studied.

Addressed Topics

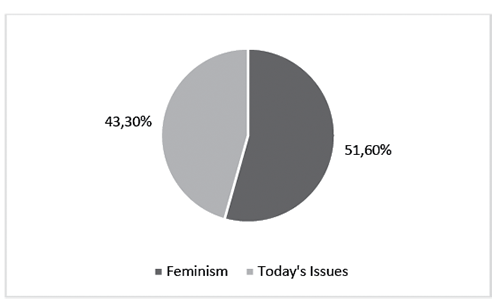

Considering the study corpus, more than half of the analysed Instagram captions refer to the topic of feminism (51.6%, 124 captions). The rest addresses other relevant issues in current life (48.3%, 116 captions). Significantly, 100% of their publications show problems that describe contemporary society, aiming to denounce them and foster activism (see Graphic 1).

Graphic 1. Type of topics addressed (own elaboration)

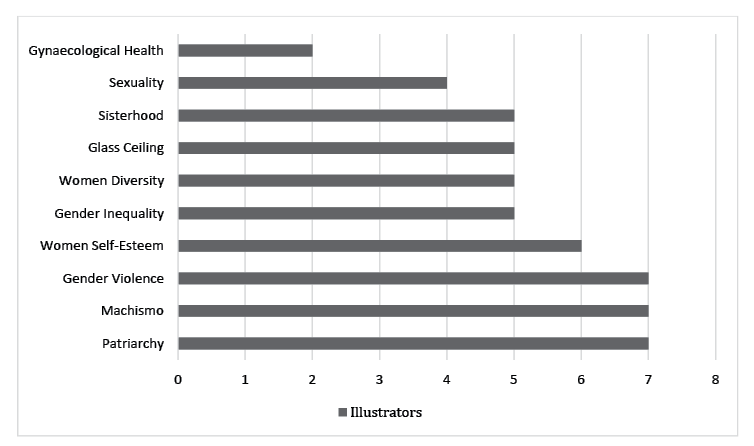

Within the feminist theme, ten specific topics are represented by the group of illustrators. In graph 2, the x-axis represents the number of illustrators who deal with each topic, showing which are the most recurrent ones.

Graphic 2. Feministic topics addressed (own elaboration)

The topics of the fight against the patriarchy (see Figure 1), the denouncing of the machismo (see Figure 2) and the gender violence (see Figure 3) are the most extended ones— seven of these illustrators address them in their Instagram captions.

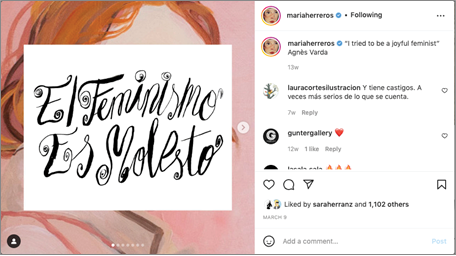

Figure 1. Caption by María Herreros against the patriarchy (@mariaherreros, Instagram).

March 9th, 2022. 1,1K likes

Feminism is annoying. It has to be. To correct an inequality someone has to lose their privileges. Annoy your boyfriend. For equality. If he doesn’t accept it, you know what he prefers.

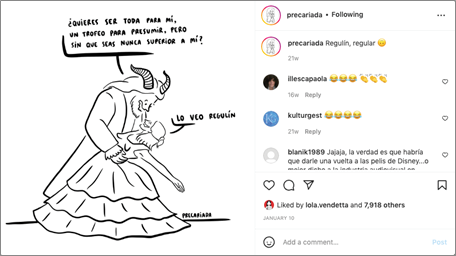

Figure 2. Caption by Precariada denouncing machismo (@precariada, Instagram).

January 10th, 2022. 7,9K likes

- Do you want to be everything to me, a trophy to show off, but never superior to me?

- Maybe not.

In Figure 1, the illustrator María Herreros presents a carousel of seven slides in which she superimposes the text on her illustrations. She develops an artivist argument encouraging the audience to transform the existing order. From the point of view of the illustrator, this transformation must necessarily be annoying for those who, until now, have lived favoured by the benefits of a society based on gender inequalities. The subversive nature of her speech makes it a clear example of artivism.

In Figure 2, the illustrator Diana Montero (whose pseudonym is Precariada) performs an intertextuality exercise recreating a scene from the famous tale The Beauty and the Beast, written by the 17th-century French writer Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve and popularised by Disney in 1991. Through ironic humour, it presents macho behaviour and the empowered response of a Belle who decides not to submit to the Beast, even when the Beast is twice her size and is in a dominant proxemic gesture over her.

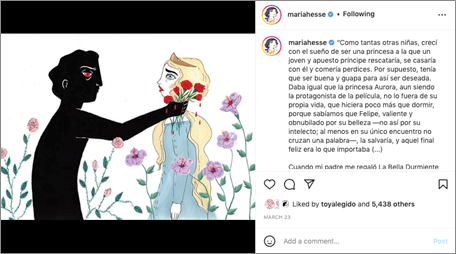

Figure 3. Caption by María Hesse denouncing gender violence (@mariahesse, Instagram).

March 23rd, 2022. 5,4K likes

Figure 3 portrays another reinterpretation of a fairy tale, Sleeping Beauty. The caption says: „Like so many other girls, I grew up dreaming of being a princess that a young and handsome prince would rescue, marry him, and live happily ever after. Of course, I had to be good and pretty to be desired. It didn‘t matter if Princess Aurora, even though she was the story‘s main character, was not the protagonist of her own life“. In the image, the prince ceases to be that fairy tale character and becomes a black and aggressive shadow that strangles the life and dreams of the beautiful princess. The illustration, so eloquent that it does not need text to be understood, is a crude portrait of gender violence. The illustrator presents gender violence as a consequence of the toxic relationships in which many women, duped by the ideal of romantic love in fairy tales, find themselves trapped.

Other feminist topics in descent order of exposure are:

• The defence of the women’s self-esteem (see Figure 4), addressed by six illustrators.

• The denouncement of gender inequality (see Figure 5) and the glass ceiling (see Figure 6); as well as the exaltation of the sisterhood (see Figure 7), represented by five illustrators.

• The awareness of the diversity in women models (see Figure 8) and sexual life (see Figure 9), by four illustrators.

• And, finally, only shown by two illustrators, the gynaecological health (see Figure 10).

Figure 4. Caption by María Gómez defending women’s self-esteem (@maria.gomez.ilustradora, Instagram).

January 16th, 2022. 21,6K likes

Translation: - I will make you very happy.

- Already I am. Much better, make for me ‘croquetas’.11

In Figure 4, María Gómez uses ironic humour to vindicate the self-esteem of women, who do not depend on the approval of men to feel satisfied and happy. The illustration shows a dialogue between the two characters in which the man plays the gallant saviour, speaking solemnly and pretending to be superior. In front of him, the woman gives a mocking and spontaneous response, demonstrating self-confidence and dismantling the myth of the hero who saves the defenceless girl.

Figure 5. Caption by Nazareth Dos Santos denouncing gender inequality on March 8th (@naza.reth, Instagram).

March 8th, 2022. 2,1K likes

We don’t want felicitations.

We want facilitations.

Figure 6. Caption by Flavita Banana denouncing the glass ceiling (@flavitabanana, Instagram).

February 17th, 2022. 39,6K likes

I don’t fit between the glass ceiling and the pelvic flor.

Nazareth Dos Santos dedicated her publication commemorating International Women’s Day to denouncing gender inequality (see Figure 5). The message is based on a play on words created with the rhetorical figure of alliteration, with the similarity between the words “felicidades” (in English, greetings) and “facilidades” (that means opportunities). With this post, the illustrator claimed the need to create opportunities for women that allow them to achieve an equal gender situation. At the same time, she warned of the uselessness of congratulatory messages to women for their international day when the creation of real measures does not accompany this gesture.

Flavita Banana denounces the glass ceiling that suffocates women in Figure 5. The illustrator portrays a woman who exemplifies society’s abusive demands on the female gender. Women must stay in shape, care for their health, be mothers, and be successful professionals; everything at once. However, society limits women’s ability to grow in their social and professional life. Among so many demands and limitations, women do not find a sphere to develop as they want and deserve.

Figure 7. Caption by Lola Vendetta exalting the sisterhood (@lola.vendetta, Instagram).

January 5th, 2022. 73,7K likes

If the Three Wise Men were the Three Wise Women:

- Mary, darling, how was the delivery?

- We brought a ham sandwich for you

- Tell us all you need and we’ll help you

Figure 6 presents a reinterpretation of the biblical scene of the Epiphany, imagining that instead of the Three Wise Men, there were Three Wise Women. The Three Wise Women empathise with the Virgin Mary, aware that childbirth is when many women feel especially physically and mentally vulnerable. They care for her, offering understanding, affection and help. This scene collapses a situation of injustice that has become traditional through the centuries and for which the mother is the great forgotten at childbirth moment. Faced with this attitude that makes women invisible, the Three Wise Women give prominence to the mother who has just given birth and show her all their support in a gesture of sorority.

Figure 8. Caption by Precariada diversity of women models (@precariada, Instagram).

January 12th, 2022. 18,3K likes

- Why do they say we are witches?

- I guess they don’t like that we are independent, intelligent, we don’t care about beauty canons and we live outside the system

Figure 9. Caption by María Gómez on sexual life (@maria.gomez.ilustradora, Instagram).

March 21st, 2022. 7,9K likes

Once again, the illustrators use the resource of fairy tales. In Figure 8, Precariada portrays two examples of intelligent and powerful women whom society despises and fears, considering them witches. This post is an opportunity to report that those women who escape the normative model of beauty and obedience suffer social rejection. At the same time, she defends and makes visible the diversity of women’s models.

In Figure 9, the illustrator María Gómez uses the lyrics of the well-known song Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door as a simile of female masturbation that knocks on the doors of pleasure. In this way, it makes visible the enjoyment and sexual self-satisfaction of women.

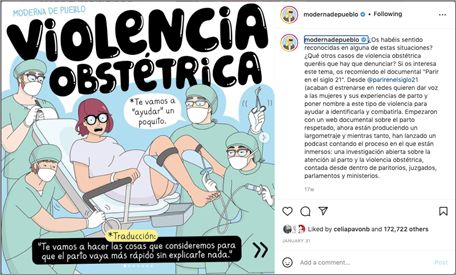

Figure 10. Caption by Moderna de Pueblo on gynaecological health (@modernadepueblo, Instagram).

January 31st, 2022. 172,7K likes

Obstetric violence.

We are going to “help” you a little.

*Translation: “We are going to do the things that we consider so that the delivery goes faster without explaining anything to you.”

Figure 10 portrays a frequent situation in numerous deliveries. Moderna de Pueblo explains how many women undergo an episiotomy12 without being informed of what this technique consists of or offered other medical options. This publication denounces situations where the woman loses the right to decide on her own gynaecological health.

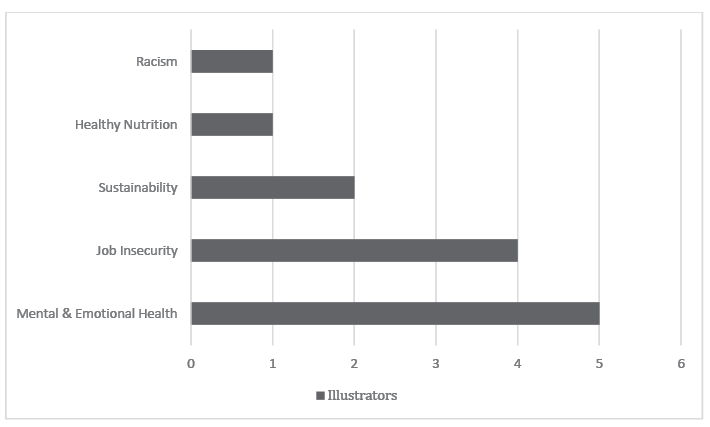

Within today’s issues, the group of illustrators represent five topics (see Graphic 3).

• Five illustrators highlight the importance of mental and emotional health (Figure 11).

• Four of them complain about the job insecurity and difficulties that young generations find when trying to get a job or climb to better positions (Figure 12).

• Two illustrators try to increase environmental and sustainability awareness (Figure 13).

• Finally, the importance of healthy nutrition and the denouncement of racist ideologies are also shown by one of the illustrators.

Graphic 3. Today’s issues topics addressed (own elaboration)

Figure 11. Caption by Lola Vendetta on mental and emotional health (@lola.vendetta, Instagram).

March 24th, 2022. 30,5K likes

How relaxing, this of forgetting self-exigence from time to time.

Like Lola Vendetta, four other illustrators of the eight analysed make the importance of mental health visible. In Figure 11, she focuses on excessive self-demand’s harmful and stressful effect on people, particularly women.

Figure 12. Caption by Flavita Banana about the job insecurity (@flavitabanana, Instagram).

January 28th, 2022. 22,1K likes

- The best thing about being self-employed is not having a boss to tell that I can’t make ends meet.

- And the worst.

- The same.

Half of the illustrators analysed address the issue of job insecurity. In Figure 12, Flavita Banana presents this topic from the perspective of self-employed workers. In Spain, the job insecurity of self-employed workers is a matter of great concern, with the female group being the most affected. Headlines such as “The gender gap is nine times greater in the self-employed than in wage earners” (González, 2023), published in the economic newspaper Cinco Días, are frequent in the Spanish press.

In Figure 13, Moderna de Pueblo humorously portrays the difficulties of a woman who has gone shopping without remembering to take her cloth bag. The character in the illustration is juggling to not ask for a plastic bag, as a gesture of respect for the environment. This publication corresponds to an institutional advertising campaign paid for by Ecoembes, a nonprofit organisation focused on caring for the environment.

Figure 13. Caption by Moderna de Pueblo about sustainability (@modernadepublo, Instagram).

January 24th, 2022. 71,1K likes

Ecogestos for uncertain futures.

Do not ask for the plastic bag (not even when you forget the tote bag).

Sense, impact and relevance of the message

The experts’ opinions reached a high degree of group consensus since the first round, where the participants already showed aligned opinions.

The following opinions reached group consensus in the set of the two rounds of the study, according to the validation criteria explained in the methodology section.

The experts consulted describe the type of message created by the illustrators as:

• A message transmitted mainly through social networks (87.5% of experts agreed).

• A message that fulfils a didactic function, promoting awareness and education of society regarding relevant issues (87.5%).

• A message that resorts to ironic humour to give visibility to social problems (87.5%).

• A message that is smart (100%).

• A message that is funny (100%).

• A message that mainly influences women (100% of the experts). “It is a vindictive and political message through humour that rescues silenced or socially minimised messages. Also, with great quality” (E513).

Experts also reflect on the women’s access to profiles and occupations that traditionally were occupied only by men: “I think they are cartoonists or illustrators who do their work reflecting women’s problems, as male cartoonists have traditionally done with their problems, fantasies and obsessions” (E7). These words show the glass ceiling that women illustrators have traditionally found in the Spanish media scene, where only male illustrators stood out and showed only issues that concerned men.

Concerning the artivism, in the round 1 open-ended questions, this concept emerged spontaneously to explain the role played by the analysed illustrators: “Art has the capacity for social transformation when used intelligently. These women know it, and they take advantage of it” (E3). In addition to defining the transformative power of art, the inflammatory nature of artivism that moves critical reflection and action is alluded to: “These illustrators create messages that are easily shared and that also generate debate and personal questions [...]. Likewise, they jump right in, something that has been strange for women, who must always be restrained, feel uncomfortable with certain topics, or not even touch them” (E5).

The following statements reflect the group consensus of the experts according to a scale of 1 to 5. Table 1 shows the measures of the centrality of the statistical distribution that demonstrate compliance with the consensus validation criteria previously established.

Table 1. Research catalysts (own elaboration)

|

Statement |

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

Interquartile range (K) |

Consensus |

|

A |

4.13 |

4 |

4 |

0,25 |

Valid |

|

B |

4.63 |

5 |

5 |

1 |

Valid |

|

C |

3.88 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

Valid |

|

D |

4.13 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

Valid |

|

E |

4.5 |

5 |

5 |

1 |

Valid |

A. “Feminism is a topic recurrently treated by the illustrators studied”. The average level of agreement with this statement is 4.13 out of 5.

B. “Aspects related to women are a recurring topic dealt with by the female illustrators studied”. Given this statement, the average degree of agreement is 4.6, with the mode (the answer most repeated by the experts) being 5.

C. “The illustrators also address other aspects related to the society in which we live”. Given this statement, the most widespread response was the value 4 (“quite in agreement”).

D. “From a generational point of view, people born after 1980 (Gen Y and Gen Z) are more influenced by the message of these illustrators”. In this aspect, the average degree of agreement was 4.13.

E. “The transmedia strategy of disseminating the message through different media favours their impact on a broader audience”. To this statement, the most repeated response was “absolutely agree” (value 5).

The lack of consensus in the group occurs when the experts propose possible ways to ensure that the illustrators’ message has a greater impact on the male audience. Some experts affirm that the key is to “launch a more empathic message towards men, which reflects everyday situations of their day to day” (statement of E6, supported by E8 and E4). They also applaud the use of humour: “I believe that humour that generates good vibes is a strategy that helps social change” (E2).

However, others distrust the success of this route and affirm that there are certain audience profiles that are “impossible to reach with a feminist message, because feminism if it is feminism, opens up a social contradiction that sexists and patriarchy cannot support” (E2).

From a more conciliatory perspective, E1 expresses her motivations and commitments regarding gender awareness: “In my case, I work and fight so that men and women in the not too distant future live in a world where they go hand in hand, never in conflict, where respect is back and forth” (E1).

In any case, being aware of the difficulties in expanding feminist awareness, some experts propose different strategies that include men and those women who do not participate in feminist ideology. In this sense, they open up new lines of research: “I think it would be interesting to ask men what itches them, what hurts them, diagnosing well what aspects of their crises can be drawn, to facilitate the necessary relaxation in their internal cordage. Likewise, I believe it is necessary to study why there are still women who defend the patriarchy and what threads bind them, to work helping others in raising awareness through the cartoon that facilitates laughter and personal and nontransferable work that everyone has to do” (E2).

Discussion

The applied methodologies allow taking complementary perspectives and analysing results consistent with each other. In this sense, the three research objectives are addressed directly, giving conclusive answers.

The hypothesis that these eight illustrators may constitute a generation of creators with characteristics common to each other and distinctive compared to the rest is confirmed. However, the possibility of identifying more illustrators that can be catalogued in this generation remains pending for future research.

It also arouses scientific curiosity to think whether the results of the Delphi study would have been the same if it had been carried out with male experts.

Nevertheless, the biggest challenge remains to determine alternatives that facilitate the spread of the feminist message beyond the female audience— even when research has demonstrated the positive effect of transmediality when it comes to spreading the message to broader audiences.

Conclusions

The communication strategy developed by this generation of Spanish illustrators rests on four pillars: feminism, transmediality, personal branding and artivism. They are not the first illustrators to reflect on gender inequality and intend to call for action. However, using social networks as their primary medium amplifies their chances of success. In fact, they represent a hybrid role between illustrators and influencers since social media is the priority scenario to activate a social transformation that starts from awareness from a rational and emotional point of view, leading to positioning and action.

They comply with most the requirement established by Petersen (1930) to constitute an author generation (González-Oñate et al., 2028; Olivares-García, 2022):

• They were born in a frame of eleven years, across the Generation Y and Z.

• They have similar education possibilities and achievements.

• They belong to a social circle that usually participates in the same type of events.

• It is difficult to identify only one generational milestone. Several events, movements and trends influence them. For example, the #MeToo phenomenon and its Spanish version #YoTambiénTeCreoHermana.

• Regarding leadership, some illustrators receive more press coverage, usually coinciding with the ranking of followers on Instagram, such as Moderna de Pueblo and Lola Vendetta.

• Nevertheless, a clear leading role in the illustrator‘s group is not identified. In general, a relationship of camaraderie and solidarity prevails between them.

• The illustrators have built a generational language since they share the same type of communication strategy regarding transmediality and the hybrid nature of their messages. There are also coincidences in the topics.

In addition to all the criteria that confirm they constitute a generation, the recurrent elements in their works are part of the fundamental ideology of feminism: body self-esteem, respect for diversity and love for all types of bodies, where different canons of beauty, different ages and races have a place (Muñiz, 2014); sorority, understood as the affection and mutual support between women for the conquest of empowerment (Martínez Cano, 2017; Sau, 2001); or the exploration and enjoyment of female sexuality, posed from an uninhibited discourse.

Their core target audience is women from Gen Y and Gen Z, while the male public and older generations remain in a broad audience position. Reaching these external audiences seems like an essential requirement for spreading gender awareness. From a strategic perspective, transmediality and hybridization favour access to wider audiences. However, the inclusion of men in feminist discourse continues to arouse doubts or opposing points of view. Therefore, a clear line of work for future research is on this point. As the experts consulted highlighted, only if we involve the male public in the feminist discourse will we be able to carry out the social transformation towards absolute gender equality.

The last conclusion corroborates that they help to break the existing glass ceiling in the Spanish media scenario, a gender inequality that occurs in the public and professional spheres, which has already been highlighted in the review of the scientific literature (Jiménez-Marín et al., 2022) and addressed by the experts consulted. They awaken reflection with a didactic and appealing discourse. A discourse that contributes to questions like the one Nochlin wondered more than 50 years ago is still open, pending an answer that contributes to creating a fairer world.

Acknowledgements

To all the experts participating in the Delphi Study. In alphabetical order by surname: PhD. María Jesús Godoy Domínguez, Philosophy Professor (University of Seville); PhD. Teresa González de la Fe, Sociology Professor (La Laguna University); PhD. Maria Medina Vicent, Philosophy Professor (Jaume I University); Marta Mediano García, Psychologist; Ana Millán Muñoz, Communication Director of the Andalusian Audiovisual Council; PhD. Victoria Tur Viñes, Chair Professor, Communication and Social Psychology, University of Alicante; María Josefa Vizuete Cinta, Second Deputy Mayor of the Town Hall of Villanueva del Río y Minas (Seville); PhD. Carmen Yago Alonso, Social Psychology professor (University of Murcia).

References

Alonso, B. (2021, December 20). 20 ilustradoras que debes seguir en Instagram. Elle Moda. https://bit.ly/40aWaH9

Álvarez, V. (2020). La narrativa transmedia del restaurante Masterchef. Razón y palabra, 24(19). https://doi.org/10.26807/ rp.v24i109.1655

Aránguez-Sánchez, T. (2019). La metodología de la concienciación feminista en la época de las redes sociales, Ámbitos. Revista Internacional de Comunicación, 45, 238–257. https://doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.2019.i45.14

Arrivé, S. (2021). Digital brand content: underlying nature and rationales of a hybrid marketing practice. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2021.1907612

Baigorri, L., & Cilleruelo, L. (2006). Net Art: prácticas estéticas y políticas en la Red. Brumaria.

Barrachina, S. G. (2019). ¿En qué contribuye el feminismo producido en las redes sociales a la agenda feminista? Dossiers feministes, (25), 147–167. http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/Dossiers.2019.25.10

Bartosik-Purgat, M., & Bednarz, J. (2021). The usage of new media tools in prosumer activities–a corporate perspective. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 33(4), 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2020.1820475

Bellido, S. (2022, January 2). Siete ilustradoras españolas a las que seguirle la pista en 2022. Diario de Sevilla. https://bit.ly/3FNbvFU

Bernárdez Rodal, A., Padilla Castillo, G., & Sosa Sánchez, R. P. (2019). From Action Art to Artivism on Instagram: Relocation and instantaneity for a new geography of protest. Catalan journal of communication & cultural studies, 11(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1386/cjcs.11.1.23_1

Borrillo, S. (2020). Chouftouhonna Festival: Feminist and Queer Artivism as Transformative Agency for a New Politics of Recognition in Post-revolutionary Tunisia. Studi Magrebini, 18(2), 203–230. https://doi.org/10.1163/2590034X-12340028

Bräuchler, B. (2022). Artivism in Maluku. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 23(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2021.2003426

Bruckmüller, S., & Braun, M. (2020). One group’s advantage or another group’s disadvantage? How comparative framing shapes explanations of, and reactions to, workplace gender inequality. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 39(4), 457–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X20932631

Burga-Díaz, M. (2021). ¿Las nuevas generaciones son siempre insurgentes? Convicciones y apuestas. Discursos del Sur, revista de teoría crítica en Ciencias Sociales, (7), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.15381/dds.n7.20899

Campos-Climent, V., Melián, A., & Sanchís-Palacio, J. R. (2014). El método Delphi como técnica de diagnóstico estratégico. Estudio empírico aplicado a las empresas de inserción en España [The Delphi method as a strategic diagnostic technique. Empirical study applied to insertion companies in Spain]. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 23, 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redee.2013.06.002

Cañedo, C. (2022, February 25). 20 ilustradoras feministas que debes seguir en Instagram. Cosmopolitan. https://bit.ly/3ndDZCd

Dashper, K. (2019). Challenging the gendered rhetoric of success? The limitations of women‐only mentoring for tackling gender inequality in the workplace. Gender, Work & Organization, 26(4), 541–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12262

De-Fina-Gonzalez, D. (2021). “A Rapist in Your Path”: Feminist Artivism in the Chilean Social Revolt. Feminist Studies, 47(3), 594–598. https://doi.org/10.1353/fem.2021.0029

De la Torre, M. (2021, November 12). Hablamos con Maria Herreros, una de las ilustradoras del momento, con motivo de su última exposición en Madrid y Barcelona. Trendencias. https://bit.ly/3ncVJh8

Espiño, A., & Patxot, M. (2021, October 10). María Herreros: “Falta que nos vean como iguales. Que no se espere de nosotras solo cómics con mirada femenina”. Pontevedra Viva. https://bit.ly/3LMiC58

Esquivel-Domínguez, D. C. (2019). Construcción de la protesta feminista en hashtags: aproximaciones desde el análisis de redes sociales. Comunicación y medios, 28(40), 184–198. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-1529.2019.53836

Fabregat, A. (2021, November 23). María Herreros: Desdibujando los límites. Metal Magazine. https://bit.ly/3K263RS

Fernández, M. G. (2022, March 8). Mensajes satíricos para reivindicar la precariedad en este 8-M: “Somos válidas y referents”. El Español. https://bit.ly/3z1n8W0

Fernández-Rincón, A. R. (2019). Activismo, co-creación e igualdad de género: la comunicación digital en la huelga feminista del 8M. Revista Dígitos, 5, 56–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12262

Freeman, M. (2021). Transmediality as an industrial form. In P. McDonald (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to Media Industries (pp. 404–412). Routledge.

Gaibar, L. (2022, March 30). Diana Montero (@precariada): “Me hace mucha gracia hacer gracia con temas que no tienen ninguna gracia”. El Salto Diario. https://bit.ly/3ZbWKTV

Gallego, J. (2021, April 28). Lola Vendetta, katana al machismo. El Diario. https://bit.ly/3LMROlg

Goldszmidt, J. (2021, February 16). Influencers feministas en Instagram: análisis de la comunicación estratégica. Communitools. https://bit.ly/42B3spq

Gómez-Diago, G. (2010). Triangulación metodológica: paradigma para investigar desde la ciencia de la comunicación. Razón y Palabra, (72). https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=199514906018

González Oñate, C., Farràn Teixidó, E., & Vázquez Cagiao, P. (2018). Rational vs emotional communication models. Definition parameters of advertising discourses. IROCAMM: International Review Of Communication And Marketing Mix, 1(1), 88–104. http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/IROCAMM.2018.i1.06

González-Oñate, C., Jiménez-Marín, G., & Sanz-Marcos, P. (2020). Consumo televisivo y nivel de interacción y participación social en redes sociales: análisis de las audiencias millennials en la campaña electoral de España. Profesional de la información, 29(5), Article e290501. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.sep.01

Guida, F. E. (2020). “Women in Italian Graphic Design History: A Contribution to Re-write History in a More Inclusive Way”. In F. Vukic & I. Kostesic (Eds.), Lessons to Learn? Past Design Experiences and Contemporary Design Practices (pp. 601–610). UPI2M BOOKS. https://bit.ly/3lODnTk

Herring, S. C. (2004). Content analysis for new media: Rethinking the paradigm. In New Research for New Media: Innovative Research Methodologies Symposium Working Papers and Readings (pp. 47–66). University of Minnesota of Journalism and Mass Communication. https://bit.ly/38uouuS

Hideg, I., & Krstic, A. (2021). The quest for workplace gender equality in the 21st century: Where do we stand and how can we continue to make strides? Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 53(2), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000222

Jakus, D., & Zubčić, K. (2016). Transmedia marketing and re-invention of public relations. Marketing Instytucji Naukowych i Badawczych, 4(22), 91–102. https://doi.org/gtb7

Jenkins, H. (2010). Transmedia storytelling and entertainment: An annotated syllabus. Continuum, 24(6), 943–958. https://doi.org/cchzjq

Jiménez-Marín, G., Bellido-Pérez, E., & Trujillo Sánchez, M. (2021). Publicidad en Instagram y riesgos para la salud pública: el influencer no sanitario como prescriptor de medicamentos, a propósito de un caso. Revista Española de Comunicación en Salud, 12(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.20318/recs.2021.5809

Jiménez-Marín, G., Álvarez-Rodríguez, V., & Palomo-Domínguez, I. (2022). Advertising and public relations degrees: profiles and the glass ceiling in the Spanish labour market. Anàlisi, 67, 87–104. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/analisi.3555

Kinder, M. (1991). Playing with Power in Movies, Television, and Video Games: From Muppet Babies to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. University of California Press.

Landeta, J. (1999). Método Delphi. Una técnica de previsión para la incertidumbre [Delphi method. A forecasting technique for uncertainty]. Ariel.

Landeta, J. (2006). Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 73(5), 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2005.09.002

Lasswell, H. (1948). The Structure and Function of Communications in Society. In L. Bryson, (Ed.), The Communication of Ideas (pp. 136–139). Harper and Brothers.

Leng, K. (2020). Art, Humor, and Activism: The Sardonic, Sustaining Feminism of the Guerrilla Girls, 1985–2000. Journal of Women’s History, 32(4), 88–109. https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2020.0041

Mandolini, N. (2022). Wonder feminisms: comics-based artivism against gender violence in Italy, intersectionality and transnationalism. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2022.2135551

Martín-García, M. T., & Martínez-Solana, M. Y. (2019). Mujeres ilustradoras en Instagram: las influencers digitales más comprometidas con la igualdad de género en las redes sociales. International Visual Culture Review, 6(2), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.37467/gka-revvisual.v6.1889

Martínez-Cano, S. (2017). Procesos de empoderamiento y liderazgo de las mujeres a través de la sororidad y la creatividad. Dossiers Feministes, (22), 49–72. http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/Dossiers.2017.22.4

Mateos-Ronco, A., & Server, R. J. (2011). Drawing up the official adjustment rules for damage assessment in agricultural insurance: Results of a Delphi survey for fruit crops in Spain. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 78(9), 1542–1556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2011.04.003

Megías, R. (2022, March 9). Mujeres ilustradoras (muy top) de nuestro país. Alto y Claro. https://bit.ly/3K1aAUz

Muñiz, E. (2014). Pensar el cuerpo de las mujeres: cuerpo, belleza y feminidad. Una necesaria mirada feminista”. Sociedade e estado, 29(2), 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-69922014000200006

Nieto, B. (2020, May 7). Despierta a la mujer libre que hay en ti gracias al congreso online Mujer Salvaje. En Femenino. https://bit.ly/3lEUvL1

Nochlin, L. (1971). Why have there been no great women artists? ARTnews.

Olmeda, A. (2021, October). María Hesse: «El dolor y la alegría cohabitan en mí y, por lo tanto, en mis ilustraciones». Jot Down. https://bit.ly/3nhernv

Olivares García, F. J. (2022). The communication of sexual diversity in social media: TikTok and Trans Community. IROCAMM: International Review of Communication and Marketing Mix, 5(1), 83–97. https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/IROCAMM.2021.v05.i01.07

Ortega, & Gasset, J. (1933). En torno a Galileo: obras completas. Revista Occidente, 5.

Palau-Sampio, D., & Cuartero-Naranjo, A. (2018). El periodismo narrativo español y latinoamericano: influencias, temáticas, publicaciones y puntos de vista de una generación de autores. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (73), 961–979. http://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2018-1291

Palomo-Domínguez, I., & Zemlickienė, V. (2022). Evaluation Expediency of Eco-Friendly Advertising Formats for Different Generation Based on Spanish Advertising Experts. Sustainability, 14(3), Article 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031090

Petersen, J. (1930). Las generaciones literarias. Filosofía de la ciencia literaria. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Prats, M. (2022, March 9). Feminismo y tetas sin “sujetadores mentales” en la noche que habría soñado Rocío Jurado. Huffington Post. https://bit.ly/3Z9u51I

Raposo, P. (2015). Artivismo: articulando dissidências, criando insurgencies. Cadernos de Arte e Antropologia, 4(2), 3–12. http://doi.org/10.4000/cadernosaa.909

Ramírez-Morales, M. R. (2019). Ciberactivismo menstrual: feminismo en las redes sociales. PAAKAT: revista de tecnología y sociedad, 9(17), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.32870/pk.a9n17.438

Ramos-Gutiérrez, M., & Fernández-Blanco, E. (2021). La regulación de la publicidad encubierta en el marketing de influencers para la Generación Z: ¿Cumplirán los/as influencers el nuevo código de conducta de Autocontrol? Prisma Social Revista de Investigación en Ciencias Sociales, (34), 61–87. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/4370

Reguant-Álvarez, M., & Torrado-Fonseca, M. (2016). El método Delphi [The Delphi Method]. Reire, Revista d’Innovación i Recerca en Educació, 9(1), 87–102. http://doi.org/10.1344/reire2016.9.1916

Renz, S. M., Carrington, J. M., & Badger, T. A. (2018). Two strategies for qualitative content analysis: An intramethod approach to triangulation. Qualitative health research, 28(5), 824–831. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526416070.n34

Reyes, E. (2020, August 13). Flavita Banana, una feminista que desmonta el machismo a punta de papel y lápiz. La Neta. https://bit.ly/3JHOyoN

Rodríguez, P. (2021, March 8). 8M: Ocho cuentas feministas de Instagram que deberías seguir. Flooxer Now. https://bit.ly/3TAOThw

Rustarazo, R. (2020, March 8). 17 Ilustradoras feministas que te inspirarán hoy y todos los días. In Style. https://bit.ly/407uF1p

Salinas, R. G., & Lomba, C. (2021). Olvidadas y silenciadas: mujeres artistas en la España contemporánea (Vol. 10). Universitat de València.

Sánchez-Gey Valenzuela, N. (2018). Los micromachismos en televisión y el papel de altavoz de las redes sociales. In Investigación y género. Reflexiones desde la investigación para avanzar en igualdad: VII Congreso Universitario Internacional Investigación y Género (pp. 742–754). SIEMUS (Seminario Interdisciplinar de Estudios de las Mujeres de la Universidad de Sevilla). https://bit.ly/3ZtYUOX

Sánchez-Rubio, D. (2017). Sheila Levrant de Bretteville y la influencia del feminismo en el diseño gráfico. Ñawi: arte diseño comunicación, 1(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.37785/nw.v1n2.a4

Sau, V. (2001). Diccionario ideológico feminista. Icaria Editorial.

Serrano, D. (2022, May 4). Las tetas zamoranas que sí dieron miedo al director del videoclip de Rigoberta Bandini. El Español. https://bit.ly/3ndABXV

Shymko, Y., Quental, C., & Navarro Mena, M. (2022). Indignação and declaração corporal: Luta and artivism in Brazil during the times of the pandemic. Gender, Work & Organization, 29(4), 1272–1292. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12793

Silverman, M. (2020). Feminist cyber-artivism, musicing, and music teaching and learning. In J. Waldron, S. Horsely, & K. Veblen (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Social Media and Music Learning (pp. 293–313). Oxford University Press.

Soufas, C. C. (2002). Julius Petersen and the Construction of the Spanish Literary Generation. Bulletin of Spanish Studies, 79(2-3), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/147538202317345014

Suárez, C. (2020, February 24). María Herreros: “Estamos obsesionados con la belleza ideal, pero la realidad es imperfecta”. Telva. https://bit.ly/408ZB1f

Suárez-Carballo, F., Martín-Sanromán, J. R., & Martins, N. (2021). An analysis of feminist graphics published on Instagram by Spanish female professionals on the subject of International Women’s Day (2019-2020). Communication & Society, 34(2), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.34.2.351-367

Thomas, M. R., Madiya, & MP, S. (2021). Customer Profiling of Alpha: The Next Generation Marketing. Ushus Journal of Business Management, 19(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.12725/ujbm.50.5

Torroella-Bribiesca, M. (2021). Vázquez Touriño, Daniel. Insignificantes en diálogo con el público. El teatro de la generación Fonca. Colindancias-Revista de la Red de Hispanistas de Europa Central, (12), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.35923/colind.2021.12.16

Visser, M. (2021). Digital Marketing. In M. Visser, B. Sikkenga, & M. Berry (Eds.), Digital Marketing Fundamentals. From Strategy to ROI (pp. 13–28). Noordhoff. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003203650

Winter, R. (2023). Generation in der deutschen Literaturgeschichtsschreibung bei Friedrich Schlegel und Julius Petersen. Germanica, 71, 33–48. https://doi.org/10.4000/germanica.18548

1 Pen name of Raquel Córcoles.

2 Pen name of Flavia Álvarez-Pedrosa Pruvost.

3 Pen name of Raquel Riba Rossi.

4 Pen name of Diana Montero.

5 While the hashtag #MeToo has become popular internationally, in Spain, the motto #YoTambiénTeCreoHermana (“I believe you too, my sister”) stands out. It emerged as a claim to support women who have denounced gender violence.

6 An illustrator woman.

7 A feminist woman.

8 A Spanish woman.

9 “Women illustrators (who are are super top) from our country”.

10 “May 8th: Eight feminist Instagram accounts you should follow”.

11 Croquetas are a typical Spanish dish consisting of a breadcrumbed and fried roll of bechamel sauce mixed with chopped ham, cheese or vegetables.

12 A cut made at the opening of the vagina while a woman is giving birth.

13 One of the methodological requirements of the Delphi method is the anonymity of the participants to avoid conditioning opinions among them. With this intention, the experts are quoted with a code assigned by the researchers (E1 = Expert 1, E2 = Expert 2...). Additionally, the Acknowledgments section includes the names and positions of the participating experts.