Informacijos mokslai ISSN 1392-0561 eISSN 1392-1487

2020, vol. 89, pp. 98–115 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2020.89.43

Mapping Technology Based Tools of Audience Engagement

Skaistė Jurėnė

PhD student, Vilnius University Kaunas Faculty, Kaunas, Lithuania

E-mail: skaiste.jurene@evaf.vu.lt

Dalia Krikščiūnienė

Professor, Vilnius University Kaunas Faculty, Kaunas, Lithuania

E-mail: dalia.kriksciuniene@knf.vu.lt

Summary In order to survive or adapt to new tendencies, cultural organisations must enhance audience engagement. This article proposes a new look at the concept of audience engagement from an integral point of view evaluating and analysing it by means of the conception of a map. The prototype of mapping audience engagement tools created in this article can help cultural organisations to effectively measure and evaluate actions in order to coordinate and select effective audience engagement tools. The empirical part of the article introduces a study of 18 Kaunas City (Lithuania) cultural organisations which reveals that organisations mostly focus on online activities, especially in the categories of accessibility and cognition, and there is a lack of collective development and more active audience engagement in programme development as well as promotion of discussions and original additional context.

Keywords: audience engagement, cultural organisations, engagement tools, maps.

Received: 01/12/2019. Accepted: 01/03/2020

Copyright © 2020 Skaistė Jurėnė, Dalia Krikščiūnienė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

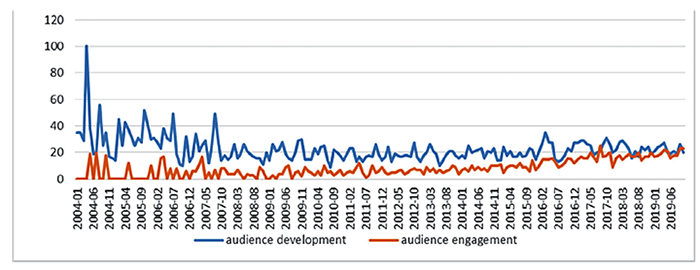

For both commercial and non-profit cultural organisations efficiency of management processes has become equally important in terms of art quality. The aspect of audience development is especially important to them because art consumption is decreasing or remains stable, however, the number and variety of art organisations is expanding (Milindasunta, 2016). Therefore, the concepts of audience development and audience engagement are more frequently discussed not only in scientific works and EU documents, but also in internet searches. According to the calculations provided by Google Trends (Fig. 1), the number of search entries for information on audience engagement has come close to the number of search entries for audience development; moreover, the most frequent and becoming most popular entries deal with audience engagement tools. Nevertheless, the analysis of scientific works reveals that there is not much information about both audience engagement and especially the tools that promote audience engagement.

Fig. 1. Audience Engagement and Audience Development in Google search

Source: trends.google.com

The term audience refers to active (participants, visitors) and passive (listeners, spectators) consumers of cultural products both physically and with the help of digital technologies. Audience development describes long-term processes that encompass the entire organisation and that are based on strategic planning, evaluation and analysis in order to respond to the needs of existing and potential audiences. Meanwhile, audience engagement is defined as a goal of an organisation to turn consumers into active participants and strengthen mutual (audience-organisation) connections thus implementing the goals of the organisation and the audience. Audience engagement creates an opportunity for the consumer to act physically, emotionally and intellectually. This allows understanding the audience better, as well as evaluating it and relating it to the experiences that the organisation proposes.

Scientific publications (Harlow, 2014, Brown, Novak, 2007, Babak, 2014 and others) propose that in order to strengthen the impact of audience engagement, cultural organisations have to employ means complementing early preparation or reflection after the event by using technologies and media based tools (e.g., filming interviews with creators, presenting backstage moments, creating blogs), means that promote participant engagement (meetings with creators, workshops, etc.), cooperation and partnership based activities, by experimenting with the existing environment or providing more diverse information in order to expand the existing context of an audience participant.

The first chapter of the article includes an analysis of the impact of technologies on audience engagement promotion tools and provides a mapping prototype for audience engagement promotion tools. The second chapter discusses the results of the empirical study of 18 Kaunas City (Lithuania) cultural organisations, points out which tools are prioritised by these organisations, includes an expert evaluation of the categories of the tools based on the DEMATEL methodology and provides an analysis of how the obtained results of the study differ from methodologies provided in theory. A map of audience engagement tools of Kaunas City (Lithuania) cultural organisations has been created.

1. Impact of technologies on tools that promote audience engagement

It is evident that culture consumption habits are changing more and more, and the most frequent culture consumption practice is online consumption. Milano (2015) points out in the article that there are prevailing tendencies in Europe to implement audience development based on digital tools and media that help to not only provide more information, but also for the audience member to use the desired content and information. New technologies are also more and more frequently used to spread information and cultural content, and strategic partnerships with IT companies are often used as well. Use of internet tools is applied in the activities of cultural organisations and is mostly based on the following three main goals: provision of information about upcoming events, activities being carried out and the programme, ability to buy tickets online or support an organisation, and ensuring mutual communication (by means of a dialogue)(Saxton, Brown, 2007). There is a strengthened aim of cultural organisations to make a transition from audience development to audience engagement, and new technologies should help to implement both of these aims (Milano, 2015). However, the impact of technologies on audience engagement promotion opportunities is rarely studied or is not employed purposefully.

From the strategic point of view, openness, faster access and easier accessibility encourage cultural organisations to use new technologies to promote audience engagement (Australia Council for the Arts, 2011), and this is becoming an important tool for cultural organisations (Mihelj, Downey, 2019). However, digitalisation and use of new technologies impacts not only the content/form created by organisations, but also the opportunities to develop connections with the audience. There is a more evident and obvious transition from analogue/physical to digital/virtual (O’Connor, 2010). The developed cultural product can be distributed by various means, and the use of technologies/internet provides broader opportunities for this purpose both for the consumer to choose how, when and where to spectate/listen and for the organisation in search for new and attractive means to provide its content (COPE strategy) (Bechmann, 2012). Moreover, with changing needs and lifestyle, and with technologies occupying a more important place (Payne, Storbacka, Frow, 2007), cultural organisations are experiencing a transition from production development for the audience to creation development together with the audience (Walmsley, 2013). In this way, not only fast and effective interaction, but also the shared creation development have become possible with the assistance of technologies thus creating trust and connection between the cultural organisation (artist) and individual, carrying out a collective action or sharing information and new resources. Digital technologies have enabled cultural organisations to not only make artwork more accessible, engage and interest new audiences, but also expand the scope of creativity by looking for new forms and means for audience engagement.

The most frequently used tools of digital marketing by cultural organisations are websites. This digital marketing activity that carries out the function of informing has been a usual practice in the activities of cultural organisations for some time (Turrini, Maulini, 2012). The following can be attributed to other frequently used online tools in the activities of cultural organisations: sending newsletters, online souvenir stores, purchasing and support of e-tickets, views or downloads of a cultural product online, virtual tours (Turrini, Maulini, 2012). It should be emphasised that as the internet is becoming a more important platform of communication, communication practices have transformed from the push stage to the pull stage. Before, an organisation used to fully control what, when and how to communicate; however, the use of online tools has changed this situation, i.e., members of the audience are provided with more and more opportunities not only to choose how, when and what to consume, but also to spread the information via existing/used channels (Milano, 2015).

Cultural organisations can use the internet for different audience development goals, i.e., to share the content created with the audience, to know additional information in order to attract audience and encourage it to share the experience with others (Uzelac, 2010). For this, not only the website, but also social media are provided.

Back in 2010, a study carried out in England revealed that 53 per cent of art consumers used the internet in relation to the arts, and this consumption not only changed, but also complemented the “live” experience. The study also refers to the fact that in the digital environment the interaction between cultural and art content is possible in the following 5 categories: accessibility (when looking for opportunities and planning participation), cognition (when looking for more information on a creative team or event), experience (when seeking for a direct experience online), sharing, creation (when creating together) (Museums, Libraries and Archives Council, 2011).

The use of social media in order to create a competitive trade mark and strengthen the connection with the audience is described in scientific literature as an important strategic tool. First of all, it is because communication on social networks not only is interactive, but it also promotes participation and cooperation thus creating significant relationships (Wan-Hsiu, 2014). Dima and Wright (2012) point out that interactive art installations can be a great way to attract the audience’s attention, engage them in activities; however, social media help to create a stronger and long-term connection with the audience by creating an opportunity to maintain and promote it. Social media helps cultural organisations to increase trust, decrease distance; it helps to share ideas, experiences and knowledge with the audience and can be a great tool not only to communicate, but also to cooperate, find out about audiences, and interact (Lotina, 2015).

In this way, the impact of technologies in organisational audience engagement promotion activities is based on not only marketing principles (increase of accessibility, dispersion of information, advertising), passive content use (viewing broadcasts of plays, listening to music), digital content provision (virtual exhibitions, recordings), but also active participation when creating (collective creation platforms, ability to add to the content being created, virtual discussion rooms, etc.).

Brown (2011) sums up possible tools that promote audience engagement and distinguishes the use of technologies as a separate category. He distinguishes the following categories: 1. Use of technologies. 2. Cooperation and partnerships with other organisations that help to expand existing resources, reach new audiences and increase engagement. 3. Experimenting with the environment when cultural organisations search for attractive and innovative ways to renew their lobbies, entrances, etc. and engage the visitor upon entering the organisation. 4. Participation and engagement when the audience is invited to not only spectate, but also engage by means of various events and tools. These categories emphasise diverse activities that encourage to not only participate and reach new audiences, but also surprise members of the audience in casual spaces; however, they do not observe the fact that all four categories may possibly in principle include technologies (interactive installation in the lobby, cooperation with IT companies or virtual reality glasses that welcome to participate and create). Also, these categories do not include tools that provide additional information for an audience member and expand their existing context thus increasing the conditions for the visitor to engage; however, they do not experiment with the environment, do not use technologies and are not based on cooperation and audience engagement (for instance, apps dedicated for a play).

Different tools and ways are applied to different audiences. Activities that are implemented physically in an organisation (in its space) aim at diversifying and expanding existing audiences. It is natural for a person to visit an organisation in order to participate in such activities. Meanwhile, digital activities aim at reaching new audiences, and increasing and maintaining audience engagement. Deepening of audience relationship an also be created through promoting active engagement and shared creation (Bollo, 2017). The aim of activities outside an organisation is to expand the audience.

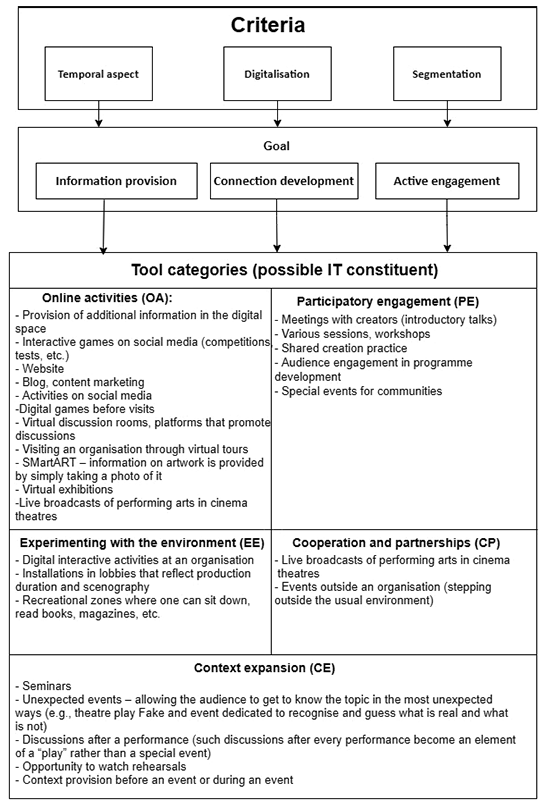

Therefore, analysing audience engagement tools we distinguish them into those that operate online (e-communication), those that promote participatory engagement, those that respond to experimenting with the environment, cooperation and partnership-based, and those that expand the context. It is important to note that technologies can be integrated into all the distinguished categories, and segmentation (which audiences they aim at) and temporal (long-term processes) aspects are important for the use of the tools.

Summing up on the IT tools described in scientific literature, they can be distinguished into those that provide additional information on the activities of an organisation (websites, blogs, social media, virtual tours and virtual exhibitions, events, music records), those that create dialogue and engaging activities (use of social media, virtual discussion rooms, SMartART, games), those that create unexpected experiences (for instance, live performing arts broadcasts in cinema theatres). These tools could be employed for evaluation from the following different perspectives: first of all, when evaluating which goal they are based on (developing mutual connection, promoting active engagement or providing additional information); second of all, when analysing how many audience members and how have engaged (it can be done on social media when evaluating reach, number of views, comments, likes), whether it has justified the strategic goals (i.e., promoted active participation, provided additional information); and third of all, when evaluating this in the context of segmentation and time (whether it is directed to the target audience, whether it is a constantly employed tool, whether it is repetitive or one-time) with regard to the fact that the audience engagement process is a long-term process based on short-term activities and projects.

Below (Fig. 2) we present the prototype of audience engagement tool mapping that reflects categorised, generalised and most frequently named tools that promote audience engagement in scientific literature based on the conception used in the article.

Fig. 2. Prototype of mapping tools that promote audience engagement

Source: created by the authors; based on Tomka (2016), Harlow & Field (2011), McCarthy (2001), Harlow & Heywood (2015), Brown & Novak (2007), Lotina (2015), Huang (2019), Milano (2015), Kawashima (2000), Frau-Meigs (2014), Brown (2011)

The tools presented in Fig. 2 can also be analysed from the audience member’s point of view, i.e., his/her goals. If analysing based on the principles (except those tools that operate online) distinguished by (Museums, Libraries and Archives Council, 2011), we notice that most of the activities discussed in theoretical works are directed towards cognition (meetings, seminars, discussions, etc.), experience (unexpected events, workshops, interactive activities), creating together (creation practice, engagement in programme development), and, significantly less, accessibility (this could include spectating rehearsals and events outside an organisation). The most effective and easiest (openness, faster and easier accessibility) way for cultural organisations to implement accessibility is to use online tools; thus, it is natural that in order to satisfy all the needs of the audience, an organisation has to employ both online and physical tools.

The mapping prototype not only generalises and categorises audience engagement tools, but can also serve as an instrument for cultural organisations to look for means to enhance audience engagement and strategically choose categories to be enhanced. It can also be used as a monitoring tool that would help to categorise and position the audience engagement tools being used to evaluate them from the temporal point of view.

In order to evaluate the validity of and ability of this mapping conception to be applied for corporate audience engagement and development strategies, an empirical study was carried out on what tools are prioritised by companies and how it is different from theoretical methodologies. The empirical study comprises of the following three stages: an analysis of data from surveying cultural organisations related to audience development strategies, a study of practical activities of these organisations on online media, and evaluation of experts based on the DEMATEL method. The results obtained during the expert study are used for an analysis and interpretation of the results of conformity between the theoretical map and the actual activities of an organisation.

2. Evaluation of the concept of mapping based on corporate activity practices

2.1. Research methodology

During the empirical research, 18 organisations that had filled out applications in August-September 2018 to participate in one-year-long audience development training organised by Kaunas – European Capital of Culture 2022. During the first stage, the questions of the surveys filled out during the application submission process were selected and generalised using the suggested concept of mapping; the selected questions reflected the experience of the cultural organisations in audience development and promoting audience engagement as well as their compliance with theoretical factors integrated into the map. During the second stage, in order to determine the tools used by organisations for audience development and to increase engagement, the qualitative content analysis method was employed to analyse the information presented online by selected cultural organisations. Analysis includes the use of information from the website sections of the organisations, news published on the website during the period of 1 January 2018 – 5 September 2019, and announcements on social media of the organisations. This selected period reflects the frequency and repetition of the tools used. Activities that are introduced and described in online content sections (not only news) were recorded as constant.

2.2. Results of the surveys

The questions provided in the survey encompass information about an organisation (its type, status, number of employees, funding sources), main and additional activities, audience research practices, and challenges that the organisations face. Out of 18 organisations under analysis, 16 are budgetary institutions funded by the municipality or the state, whereas 2 organisations have the status of non-profit making organisations. In filling out the surveys, the organisations were characteristic of diversity – most of the applications were submitted by performing arts organisations (5), museums (4) and interdisciplinary cultural centres (4). 2 libraries, 2 galleries and 1 biennial.

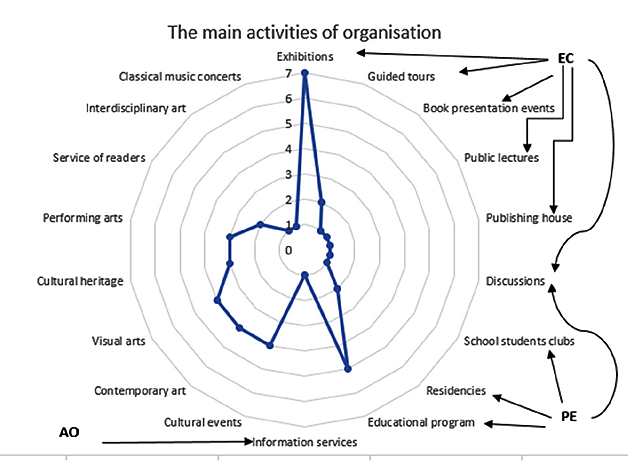

Fig. 3. Main activities of the organisations sorted based on category of tools (N=18)

Source: created by the authors

The main constant activities that the operating organisations pointed out are mainly an expansion of context (EC) (exhibitions, guided tours, book presentation events and etc.), participative engagement (educational activities, school student clubs, residencies and etc.), activities online (information services). Even though not all the organisations pointed out educations along with the main activities (only 5 out of 18 mentioned it) but 94% of them pointed out that they were implementing educational programs when this question was provided in the upcoming stages. This shows that many of the organisations see educational activities as an additional activity that creates added value or is irregular, but participative engagement is a very important element for audience engagement. 15 out of 18 organisations point out to be collecting and accumulating information on audiences. The main information collection methods are as follows: data of sales and registration systems, online and physical surveys, data of the loyalty program. The least collected pieces of information deal with age and the exact number of visitors. The provided data shows that organisations mostly carry out registrations to events or collect information to send newspapers (collecting email address 72 percent), and collect statistical data rather than to figure out the true needs of audience and to know the audience better (segmentation), 50% of organisations use the data to promote events, and only 35% analyse the data when planning new programs, 15% of the organizations collect data yet do not analyse it. This research reveals that cultural organisations in Kaunas mainly focused on marketing, but not audience engagement. Because of that, we carried out a qualitative analysis of the websites and social media data, seeking to understand what kind of audience engagement measures cultural organisation uses.

2.3. Qualitative analysis of website and social media content

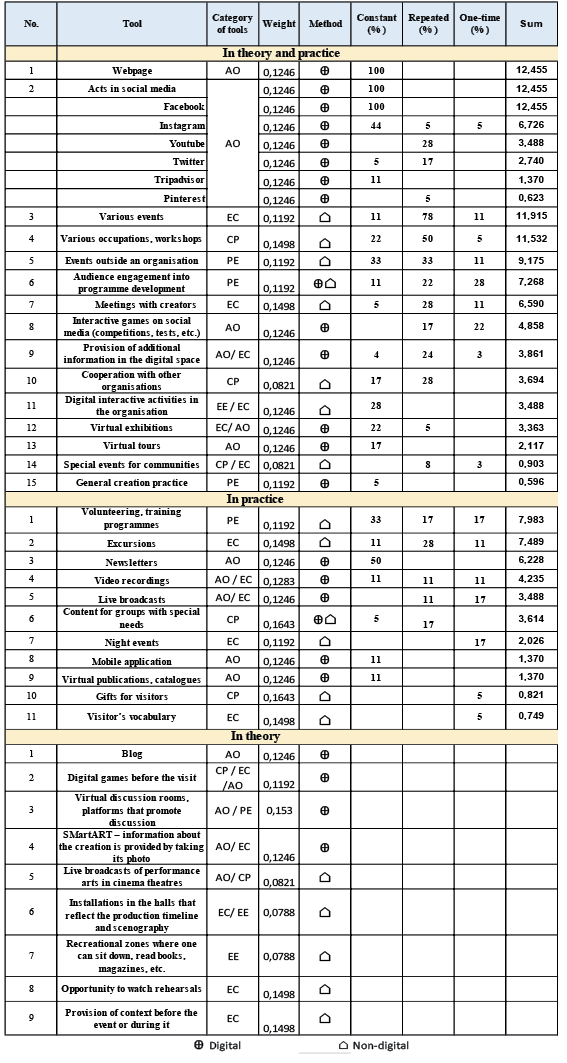

Having analysed the data on the websites and social networks of the organisations, a map of audience development and engagement promotion tools in Kaunas cultural organisations was created (see Fig. 8). According to the frequency of use of the tools in an organisation, they were distinguished into constant, repeated (mentioned on the news 3-5 times) and one-time (occurring 1-2 times). According to the operation space, they were distinguished into offline (operating in the space of an organisation or other physical spaces) and online (operating in digital tools). Every tool indicates a space (offline/online) and frequency of use in each organisation (e.g., if two categories that use the same tool are under analysis and they are constantly offline, two black houses are marked). The aspect of segmentation is analysed where the data was introduced.

The qualitative content analysis shows that one of the most popular constant tools is communication and promotion of engagement on Facebook. Social network Instagram is used less frequently and is especially rarely used (only one-time in one of 4 organisations) in interdisciplinary cultural centres. YouTube is used by museums and performance arts institutions. Meanwhile galleries and some of the museums also publish their activities on Twitter, and one of the museums sometimes uses Pinterest.

The second most frequently used tool (repeated the most) encompasses various events that add to an organisation’s activities (for instance, film reviews or concerts in the library, literary reading sessions in the theatre, etc.). Organisations use these activities to develop their audience and promote their engagement by providing various new experiences.

The third tool in the map deals with educational occupations that are intended for various audiences, i.e., families, children, seniors, etc. These activities are often repeated or constant in almost all of the organisations. This can be found among constant tools mainly in museums.

Almost all organisations constantly or repeatedly carry out activities outside the organisation; this includes various participations in the city, national or foreign festivals, display of exhibits in other organisations or public places, etc. These are also important tools in order to attract new audiences.

A volunteering programme is the most popular in libraries and museums and are carried out 100% there; however, not all of the organisations have it as a constant practice. For instance, 50% of museums implement volunteering only in random cases when they look for volunteers for a specific event. An organisation may try to keep the volunteers in their daily practices; however, there is no information about this.

Over 60% of organisations try to engage audiences in various activities by sometimes suggesting to join the process of generating ideas, applying in various invitations, providing items (e.g., a bathtub in a festival’s advertising campaign or a guitar in the implementation of the play).

In order to introduce audiences to the backstage of an organisation, the personalities who create there or creators who are presented, social networks are used to present information about them, share their thoughts and insights. Thematic excursions are mostly employed in performance arts organisations. Newsletters occupy the tenth place among the tools used..

The least used tools include a collective creation promoting platform that one museum has established. However, theoretical works provide the invitation to create content together as an important element that promotes audience engagement.

Virtual tours, mobile applications and virtual museums, expositions are also not frequently used tools. Events for people with special needs (e.g., plays for the deaf and hard-of-hearing, the blind) or adaptation of content for them (video recordings with sign language) help organisations to attract target audiences; however, only sporadic organisations employ these tools.

The qualitative analysis of websites and social media content reveals the audience engagement tools used by the selected Kaunas cultural organisations. The presumption is that websites and Facebook that are actively used by cultural organisations allow collecting the main and most frequently used tools that promote audience engagement; however, there was no opportunity to evaluate how this complies with the strategies selected by the organisations and the target audiences. We note that some of the organisations actively employ various digital tools when promoting audience engagement, they use various events and educational programmes, which is likely to promote participatory engagement; however, it does not pay attention to promotion of discussions or audience’s engagement in programme development. Such activities require more time spent on human resources, getting to know one’s audiences better and be willing to create a real mutual dialogue.

Summing up the data obtained during both of the stages, it can be presumed that the analysed cultural organisations carry out audience development and audience engagement activities more intuitively rather than strategically. They do not collect data on audience needs, preferences, and do not tend to analyse the collected data when planning further activities. The most frequently used audience engagement tools are similar in all the organisations, and the exceptional ones are not usually used consistently. However, in order to evaluate and rate what weight each of the tool category has as well as what their mutual connection is, expert opinions were taken into account based on the DEMATEL method.

2.4. Expert evaluation of audience engagement tools based on the DEMATEL method

The Decision-making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) is seen as an effective method when analysing the connections of cause and effect between the components of a system and evaluating their importance. DEMATEL can confirm the interdependency of factors and help when creating a map that would reflect relative connections inside them (Sheng-Li Si et al. 2018). Based on this method, three experts were interviewed (namely, one head of the management department of an organisation, one marketing specialist in an organisation, and one audience development expert), and they were asked to evaluate the strength of the connection, impact and effect (when 0 – no impact, 1 – low impact, 2 – medium impact, 3 – high impact, 4 – very high impact). 8 following factors were evaluated: online activities (OA), cooperation and partnerships (CP), experimenting with the environment (EE), context expansion (CE), connection development (CD), information provision (IP), active engagement (AE) and participatory engagement (PE).

Step 1. Calculation of the average Z matrix was carried out using Eq. (1).

|

|

|

OA |

CP |

EE |

CE |

CD |

IP |

AE |

PE |

Sum |

|

|

OA |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

17 |

|

|

CP |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

14 |

|

Z= |

EE |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

13 |

|

|

CE |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

16 |

|

|

CD |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

15 |

|

|

IP |

4 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

17 |

|

|

AE |

3 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

19 |

|

|

PE |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

13 |

|

|

Sum |

13 |

4 |

5 |

22 |

27 |

16 |

21 |

16 |

|

Fig. 4. Calculations of average Z matrix

Source: created by the authors

Factor evaluation importance was determined by (R + C) values. According to Table 1, connection development (CD) is the most important element whose highest value (R + C) is 3.637447, whereas the least important factor is experimenting with the environment (EE); here R + C – 1.660962. With regard to R+C values, factors set out according to the following priority of importance: connection development (CD) > active engagement (EA) > context expansion (CE) > information provision (IP) > online activities (OA) > participatory engagement (PE) > cooperation and partnerships (CP) > experimenting with the environment (EE).

Step 2. Normalised initial direct connection matrix X was calculated using Eq. (2) to Eq. (5).

|

S= |

19 |

|

or |

|

S= |

27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

OA |

CP |

EE |

CE |

CD |

IP |

AE |

PE |

|

|

OA |

0 |

0.04 |

0 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

0.111 |

0.04 |

|

|

CP |

0.04 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.07 |

0.15 |

0.04 |

0.111 |

0.07 |

|

X= |

EE |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.07 |

0.11 |

0.11 |

0.111 |

0.07 |

|

|

CE |

0.11 |

0 |

0.04 |

0 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

0.074 |

0.07 |

|

|

CD |

0.07 |

0.07 |

0.04 |

0.07 |

0 |

0 |

0.148 |

0.15 |

|

|

IP |

0.15 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

0 |

0.111 |

0.04 |

|

|

AE |

0.11 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

0.07 |

0 |

0.15 |

|

|

PE |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

0.07 |

0.111 |

0 |

Fig. 5. Normalised initial direct connection matrix X

Source: created by the authors

Step 3. The total connection matrix T was calculated using Eq. (6) to Eq. (7), as pointed out further.

|

|

|

OA |

CP |

EE |

CE |

RD |

IP |

AE |

PE |

sum |

|

|

OA |

0.13 |

0.08 |

0.04 |

0.3 |

0.33 |

0.25 |

0.256 |

0.17 |

1.55 |

|

T= |

CP |

0.13 |

0.03 |

0.07 |

0.2 |

0.29 |

0.12 |

0.229 |

0.18 |

1.26 |

|

|

EE |

0.09 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.2 |

0.25 |

0.19 |

0.22 |

0.17 |

1.18 |

|

|

CE |

0.21 |

0.04 |

0.07 |

0.16 |

0.31 |

0.24 |

0.217 |

0.19 |

1.45 |

|

|

RD |

0.16 |

0.1 |

0.07 |

0.22 |

0.17 |

0.11 |

0.266 |

0.25 |

1.34 |

|

|

IP |

0.25 |

0.04 |

0.08 |

0.3 |

0.33 |

0.12 |

0.255 |

0.17 |

1.55 |

|

|

AE |

0.22 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

0.31 |

0.34 |

0.2 |

0.168 |

0.27 |

1.67 |

|

|

PE |

0.1 |

0.03 |

0.04 |

0.26 |

0.28 |

0.16 |

0.22 |

0.11 |

1.19 |

|

|

Sum |

1.29 |

0.43 |

0.48 |

1.95 |

2.3 |

1.39 |

1.83 |

1.52 |

11.2 |

Fig. 6. Total connection matrix T

Source: created by the authors

According to (R-C) values (Table 1), eight factors were distinguished into (I) cause group and (II) effect group. If (R-C) value is positive, such factor is attributed to the cause group and has direct impact on other factors. The highest (R-C) factors have the highest direct impact. In this study, online activities (OA), cooperation and partnerships (CP), experimenting with the environment (EE) and information provision (IP) were classified in the cause group whose (R-C) values were respectively 0.254565, 0.822447, 0.705549 and 0.156013. The most significant factor in the cause group is cooperation and partnerships (CP).

Table 1. Direct and indirect impact of criteria

|

Factors |

According to weight |

Weight: |

R+C |

R-C |

|

|

1 |

Online activities |

5 |

0.124554 |

2.840989 |

0.254565 |

|

2 |

Cooperation and partnerships |

7 |

0.082098 |

1.690654 |

0.822447 |

|

3 |

Experimenting with the environment |

8 |

0.078801 |

1.660962 |

0.705549 |

|

4 |

Context expansion |

3 |

0.149772 |

3.393558 |

-0.49781 |

|

5 |

Connection development |

1 |

0.164274 |

3.637447 |

-0.95994 |

|

6 |

Information provision |

4 |

0.128335 |

2.934813 |

0.156013 |

|

7 |

Active engagement |

2 |

0.153015 |

3.500493 |

-0.1599 |

|

8 |

Participatory engagement |

6 |

0.11915 |

2.709681 |

-0.32092 |

|

Average |

2.796074464 |

||||

Source: created by the authors

If (R-C) value is negative, such factors are attributed to the effect group and are impacted by other factors. This group includes context expansion (CE), connection development (CD), active engagement (AE) and participatory engagement (PE), with R-C values being namely -0.49781, -0.95994, -0.1599, -0.32092. Other factors have the highest degree of impact on connection development, which, according to the theoretical material, is also understandable because connection development is one of the main audience engagement goals.

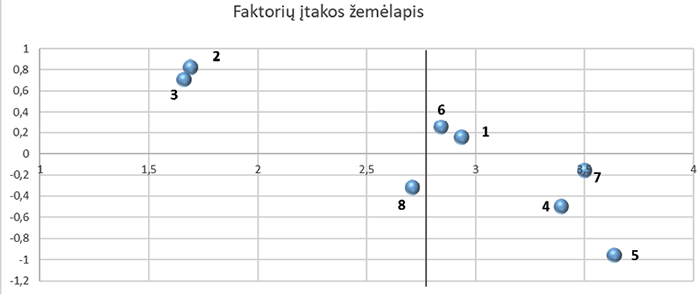

The map of the factor impact (Fig. 7) reflects how the cause and effect groups are set out graphically. Information provision (IP) and online activities (OA) are the main factors that have high significance and impact. Cooperation and partnerships (CP) as well as experimenting with the environment (EE) are autonomous, leading factors that are characteristic of low significance yet strong connection. Context expansion (CE), connection development (CD) and active engagement (AE) are the cause factors that have high impact yet low connection (they are not impacted directly). Participatory engagement (PE) is an independent factor that is characteristic of low impact and low connection.

Summing up the obtained data, it can be concluded that the most important tools that cultural organisations should employ are those that create connection, and the factors that have the most impact are information provision which helps to expand one’s context, and e-communication whose tools create and maintain connection, however, it also expands the existing context of the audience members. The lowest amount of impact by means of other tools can be put on participatory engagement; however, this is also an important factor that operates separately and helps to create connection, complements the existing context and provides new experiences for the audience member. The following section will refer to how the audience engagement tool map is comprised and how the expert evaluations reflect the tools discussed in the theoretical part.

Fig. 7. Factor impact map

Source: created by the authors

2.5. Comparison of the results of the empirical and theoretical parts

Analysing the created audience development tools map of Kaunas cultural organisations and the created map prototype (Fig. 2), it can be noted that Kaunas cultural organisations use approx. 60% of the tools introduced (see Fig. 8). There is a lack of collective creating and active audience engagement in programme development as well as in discussion promotion; also, there is a lack of originally presented additional context (during unexpected events or search for different forms); however, such tools as social media, various educational workshops, meetings with creators, activities outside an organisation, video recordings from backstage, virtual tours and exhibitions, digital interactive activities in organisations (especially museums, libraries) are actively used. Also, additional context in the digital space is provided with much attention paid to creators, their thoughts or interesting facts about historical events, introduction of the employees of an organisation, etc., which also promotes a higher degree engagement. The tools that are not described in theory yet are implemented in practice include volunteering and training programmes because they are a great way to not only expand the audience, but also increase engagement (especially of young audience), for instance, one of the theatres under analysis includes a team of about 100 volunteers (schoolchildren) every season who not only participate in the activities of the theatre, watch plays, but also discuss it with their friends and other schoolchildren. We also note that Kaunas cultural organisations work with special needs groups by not only organising various events for them, but also adapting their content for them. The tools that are introduced in theory but not reflected in practice include blogging, virtual discussion rooms, the SMartART function, installations in spaces of an organisation that provide additional context, etc. Having evaluated the tools based on experts’ evaluations as well as the frequency and popularity of use, it can be noted that the most significant five tools include websites, activities on social media, various events, events outside an organisation, and educational sessions and workshops. The tools only used in practice include volunteering, training programmes, excursions and newsletters.

Fig. 8. A map of audience development tools of Kaunas City (Lithuania) cultural organisations

Source: created by the authors

Analysing the tools mentioned in audience engagement mapping according Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (2011), Brown (2011) and the typology provided, we can see that organisations apply most of the tools online, especially when focusing on reach and cognition categories, and less – on sharing and creation categories. There is no opportunity for audience members to get experiences in the digital space. Meanwhile, offline activities in an organisation focus mostly on experience and cognition categories when creation is possible not only in volunteering, doing training (this depends on the type of volunteering as well), but their accessibility is also created by means of activities outside the organisation. In this case, participative engagement is the most actively implemented.

However, according to existing data, organisations cannot satisfy all the needs of the audience, especially creating together, promoting discussions, originally presented additional context. However, in order to provide general conclusions, it would be purposeful to carry out additional qualitative interviews with representatives of the organisations as well as a study of the audiences of the organisations to identify the needs they have for online and offline activities.

Conclusions and recommendations

In this article, we have provided a novel generalisation of the concept of audience engagement by using the concept of mapping, thus grounding the importance of audience engagement in the modern process of cultural organisations. We have emphasised the longevity of these activities and the necessity to encompass the entire organisation thus complementing its main goals and strategic plans, perceiving the audience as the central axis of an organisation. We have grounded the importance of technologies in the context of audience development and engagement. In order to generalise and categorise the audience engagement tools, we propose a map prototype that can also serve as a tool for cultural organisations in search for tools to strengthen audience engagement and strategically selecting the categories to be strengthened. This tool enables evaluating, analysing, categorising and positioning audience engagement tools being used.

The developed tool was tested when carrying out a quantitative and qualitative study of 18 Kaunas cultural organisations; this study revealed their priorities for audience engagement activities. These cultural organisations carry out audience development and audience engagement activities more intuitively rather than strategically. They do not collect data on audience needs, preferences, and do not tend to analyse the collected data when planning further activities. The main audience engagement tools used are similar among all the organisations, and those that are exceptional are not usually used constantly. Meanwhile, according to experts’ evaluations, the most important tools that cultural organisations should employ are those that create connection, whereas the factors that have the most impact are provision of information and e-communication.

Using 60% of tools defined in scientific literature and not creating conditions for mutual creation, active engagement in creating a programme, organisations cannot satisfy all the needs of their audience. However, it is recommended to carry out additional qualitative interviews with representatives of the organisations that would complement the information found online and on Facebook, as well as a quantitative study of audiences in order to determine which needs (cognitive, accessibility, experience, sharing or creating) members of the audience have. This would allow evaluating how an organisation satisfies existing audience needs and what tools can enable it to make this process even more successful.

Literature

AUSTRALIA COUNCIL FOR THE ARTS, (2011). Connecting:// arts audiences online.

BECHMANN, A. (2012). Towards Cross-Platform Value Creation. Information, Communication & Society, 15(6), 888–908.

BOLLO, A. (2017). Study on Audience Development - How to place audiences at the centre of cultural organisations.

BROWN, A. (2011). Making Sense of Audience Engagement. The San Francisco Foundation.

BROWN, A., NOVAK, J. (2007). Assessing The Intrinsic Impacts Of A Live Performance. WolfBrown.

DIMA, M., WRIGHT, M. (2012). Designing for Audience Engagement.

FRAU-MEIGS, D. (2014). “European cultures in the cloud”: Mapping the impact of digitisation on the cultural sector.

HARLOW, B., FIELD, A. (2011). Building Deeper Relationships: How Steppenwolf Theatre Company Is Turning Single-Ticket Buyers Into Repeat Visitors.

HARLOW, B., HEYWOOD, T. (2015). Getting Past: It‘s Not For People Like Us: Pacific Northwest Ballet Builds a Following with Teens and Young Adults. The Wallace Foundation.

HUANG, R. (2019). Research on Audience Engagement in Film Marketing - Taking the film <Us and Them> as the Case.

KAWASHIMA, N. (2000). Beyond the Division of Attenders vs. Non-attenders: a study into audience development in policy and practice. Centre for Cultural Policy Studies.

LOTINA, K. L. (2015). Exploring Engagement Repertoirs in Social Media: the Museum Perspective. Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics, 9(1), 123–142.

MCCARTHY, K., JINNET, K. (2001). A new framework for building participation in the arts. RAND.

MIHELJ, S., DOWNEY, J. (2019). Culture is digital: Cultural participation, diversity and the digital divide. New Media&society, 21(7), 1465–1485.

MILANO, C. (2015). Mapping of practices in the EU Member States on promoting access to culture via digital means.

MILINDASUTA, P. (2016). Audience Engagement Strategies for New World Performance Laboratory: a Proposal .(Electronic Thesis or Dissertation). Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/

MUSEUMS, LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES COUNCIL (2011). Digital Audiences: Engagement with Arts and Culture Online, 2010. UK Data Service. SN: 6842, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6842-1

O’CONNOR, J. (2010) The Cultural and Creative Industries: A Literature Review. 2nd ed. Newcastle: Creativity, Culture and Education

PAYNE, A. F., Storbacka, K. & Frow, P. (2007). Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0070-0

SAXTON, G., BROWN, W. A. (2007). New Dimensions of Nonprofit Responsiveness: The Application and Promise of Internet-Based. Public Performance & Management Review, 31(2), 144–173.

SHENG-LI S. et al. (2018). DEMATEL Technique: A Systematic Review of the State-of-the-Art Literature on Methodologies and Applications,” Mathematical Problems in Engineering, vol. 2, 33 pages, https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3696457.

TOMKA, G. (2016). Guidebook for hopefully seeking the audience.

TURRINI, A., Maulini, A. (2012). Web communication can help theaters attract and keep younger audiences. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 18(4), 474–485.

UZELAC, A. (2010). Digital culture as a converging paradigm for technology and culture: Challenges for the culture sector. Digithum.

WALMSLEY, B. (2013). Co-creating theatre: Authentic engagement or inter-legitimation? Cultural Trends,, 22(2), 108–118.

WAN-HSIU, S. T, Li njuan, R. M. (2014). Consumer engagement with brands on social network sites: A cross-cultural comparison of China and the USA. Journal of Marketing Communications.